Running head: PARENT AND ADOLESCENT DISCREPANCY

advertisement

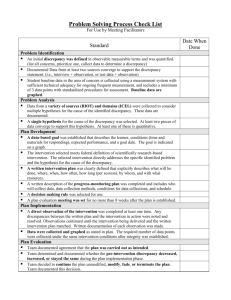

Running head: PARENT AND ADOLESCENT DISCREPANCY Discrepancies between Parent and Adolescent Responses to Survey Questions Joanna R. Price Mentored By: Dr. Ken Wallston and Dr. Shelagh Mulvaney 7 April 2010 Psychology 2990 Professor Smith Vanderbilt University Discrepancies 2 Abstract: This study examined the congruency of adolescent and parent perceptions of adolescent diabetes self-management and problem solving. Survey responses were collected from 115 adolescent- parent dyads. Parents’ and adolescent’ responses to problem solving and self-management surveys were studied to determine the agreement between their responses and the relationship to the adolescents’ hemoglobin A1c, age and gender. Simple discrepancy scores were computed for each dyad for each questionnaire and were calculated by subtracting the mean child score for each item from the mean parent score for the same item, then summing over the items. A squared discrepancy score was also calculated for each dyad per survey to magnify the discrepancy results. Bivariate correlations were run for the four discrepancy scores along with A1c, child’s gender and age. The results indicate that while no variables were significantly related with A1c, there was a high correlation between the parent and adolescent scores. Discrepancies 3 Living with a diagnosis of diabetes during the adolescent years can become a constant struggle. Teenagers are trying to rely less on their parents for help and have to begin balancing their diabetes care with the rest of their life. Diabetes care is a very complex, lifelong process, but it is essential for survival. Children often struggle with managing their disease during the adolescent years because they are beginning to take full responsibility for their diabetes management. They have to learn to balance their self-care, their school lives and many other aspects of teenage life. Parents become less involved as the care responsibilities shift to the adolescent. Self-management and problem solving become critical skills needed in order to keep diabetes under control. There are many factors such as coping behaviors and family involvement that have an impact on how adolescents self-manage their diabetes. Diabetic self-management can be measured through HbA1c levels, which is the amount of glycated hemoglobin in your blood. HbA1c measures control of blood sugar over approximately three months. It is a good indicator of diabetes control over a period of several months. Normal levels of HbA1c are 6% or less, however, in people with diabetes, they should try to keep their HbA1c levels to 7% or less (Dugdale 2009). This research study, part of a larger study being conducted by Dr. Shelagh Mulvaney, targeted adolescents, aged 13-17, with Type I diabetes. As stated by the American Diabetes Association (2008), Type I diabetes occurs when the body has an inability to produce insulin, blocking cells from gaining needed glucose. Care for Type I diabetes usually includes checking blood sugar multiple times a day, injecting insulin and calculating dietary intake. One hundred and fifteen dyads consisting of adolescents with Type I diabetes and their caregivers, mostly mothers, were given the same problem solving and self-management questionnaires to complete. By subtracting the child’s responses to these questionnaire items from the parent’s responses, we were able to determine the similarities and differences Discrepancies 4 between each dyad on each questionnaire and use this information to infer the closeness of the parent-child relationship. In order to best analyze the discrepancy between responses, scores were calculated in two different ways. It is important to look at both the direction and magnitude of the discrepancy scores. Simple differences were calculated to show the direction of the discrepancy, whether parents or adolescents rated the adolescent higher in selfmanagement and problem solving. The squared differences heightened the amount of discrepancy and showed which dyads had more differences. This study looked at whether parent-child discrepancy scores showed any correlation with the adolescents’ diabetes control, the age of the adolescent, and whether the adolescent was a male or female. One research question looked at whether the degree of congruency between children’s and parent’s questionnaire responses had an effect on the HbA1c levels of the adolescent. It was predicted that the adolescents in the discrepant parent-adolescent dyads would have poor A1c levels. It was also predicted that parent-child dyads would correlate across both questionnaires, meaning the degree of discrepancy on one questionnaire will be correlated with the degree of discrepancy on the other questionnaire. Other factors, including age, and gender were also studied to see if they had a relationship with the discrepancy scores. These research questions showed different ways to look at the responses between children and parents in relation to diabetes management. Relevant Literature There have been many research studies done on parent and child communication related to diabetes care and self-management. Family involvement is an important part in selfmanagement because the family becomes a support system. Adolescents with diabetes reach a point where they have to learn how to self-manage their diabetes in order to gain more Discrepancies 5 independence. This process can be difficult for some, but family support and communication can be a way to reduce the stress and anxiety of the situation. Parental Support and Coping An important factor in how children self-manage their diabetes is the degree of support they have from family. Previous studies have looked specifically at parental and child relationships and how these relate to self-care and management. Family support, especially the parent-child relationship in the care of diabetes, plays a huge role in the success of management. Berg et al. (2007) focused on the mother- child relationship in relationship to diabetes management. The collaboration and support of 127 children, aged 10-15, with Type I diabetes and their mothers were tested. Several important findings resulted from this study, such as the child-parent involvement in diabetes management is important for children’s and mothers’ emotional adjustment. According to Berg et al. (2007), better appraised support and collaboration between mothers and their adolescents leads to better mood and less depressive symptoms. Collaborative coping leads to mothers and children maintaining engagement and successfully caring for diabetes. McDougal (2002) focused on family support and normalization. This case study determined that normalization leads to a nurturing family environment that helps children adapt easier to their life with diabetes. Family support is an important factor in the normalization process and can be achieved through successful adaption by parents and promotes normalcy which helps with the child’s adaption to their condition. It is important to recognize that this was a case study and looked at only one family. By looking at one family, it was not representative of the population as a whole. Although this was a case study, this article also included a literature review that focused on normalization and family environment which was used to support the case study to strengthen the findings. Discrepancies 6 Stallwood (2005) studied seventy-three caregivers and looked at how caregiver stress and coping played a role in the care of children with diabetes. The results of this study showed that families of younger children with diabetes had higher levels of stress, specifically diabetes related stress. Perceived stress of caregivers may be a motivator for successful glycemic control, meaning the more stress parents have about managing their child’s diabetes leads to closer adherence to diabetes management. This study also stressed the importance of assessing parental stress along with glycemic control and providing intervention for high amounts of caregiver stress. For my research study, it is important to note the importance of age and to analyze the data to determine if a child’s age plays a role in the correlations. With the support of the studies mentioned above, it can be predicted that more parental support can lead to better care of diabetes. Parental Monitoring The degree to which parents monitor and assist their children with diabetes care is an important aspect to consider when looking at diabetes control, and becomes more challenging particularly during adolescence when the child begins to spend more time away from home. Lewandowski et al. (2006) discusses how conflict between parents and adolescents is correlated with poor adherence to diabetes treatment. In that study, fifty-one mothers of adolescents with diabetes completed questionnaires about conflict around diabetes, social support and adolescent autonomy with their diabetes care. Results of the Lewandowski et al. study show that higher levels of spousal support led to less diabetes-centered conflict and closer adherence to treatment. The amount of conflict over diabetes care was correlated with glycemic control. Discrepancy scores for that study were calculated by taking the absolute value of the difference between mother and adolescent total scores on the decision-making autonomy measure. This measure focused on the amount of discrepancy rather than a Discrepancies 7 direction for the discrepancy. Lewandowski et al. discovered that mothers and adolescents had a moderate level of discrepancy regarding who was responsible for diabetes care. The Lewandowski at al. study shows how mothers and adolescents differed in their survey answers on autonomy and how parental involvement with diabetes care leads to better adherence to treatment. Anderson et al. (1999) looked at how parent and adolescent teamwork plays a role in diabetes management. The 85 patients in the study were assigned to one of three study groups: teamwork, attention control or standard care. Adolescents were followed for 24 months and came in for regular medical appointments four times during that time period. The standard care group just came in for routine visits. The teamwork intervention and the attention control condition received 20-30 minute intervention sessions after each visit with the doctor. The teamwork intervention focused on the importance of sharing responsibility between parents and adolescents. The control group was given traditional diabetes information without a focus on parental involvement. The results show that the families assigned to the teamwork group had less conflict, and more adolescents in this group improved their HbA1c levels compared to the other two groups. This study shows how important parental involvement could be in diabetes care. Finally, Ellis et al. (2007) emphasized the importance of parental monitoring of diabetes care. This study gave self-report questionnaires to 99 adolescents and their caregivers. These questionnaires rated parental supportive behaviors towards the adolescent’s diabetes care. Parental monitoring was measured through the Parental Monitoring of Diabetes Care scale (PMDC) and diabetes management was measured by the Diabetes Management Scale (DMS). Based on the parent and adolescent reports, diabetes monitoring was correlated with adherence to diabetes care. The Ellis et al. study showed that parental monitoring of their Discrepancies child’s diabetes care leads to better adherence and better adherence to care is correlated with better HbA1c levels. These studies all looked at parental monitoring of adolescents with diabetes and how that influenced adherence to care regimens. All three studies mentioned showed that close parental monitoring in the adolescents’ diabetes care was correlated to better adherence to routines which, in turn, was correlated with better HbA1c levels. This showed that parental monitoring is indirectly correlated with better HbA1c levels. With the support of these studies, it was predicted that parental monitoring will lead to more congruency between parent-adolescent dyads which will lead to better diabetes management. It is hypothesized that if parents and children have high levels of agreement on one aspect of diabetes management, such as the child’s ability to self-manage diabetes they should also have higher agreement on the other aspects of diabetes management, such as the child’s ability to solve diabetes self-management problems. If parents are not involved in their children’s diabetes care, it is predicted that they will be less likely to be congruent with their adolescent on the survey responses. These studies show the importance of parental involvement with their adolescent’s diabetes care. Parent and Child Congruency An important concept for this research study is the idea of parent-child congruency in responses to survey questions. Many past studies have looked at the relationship between parent and child responses. Peterson et al. (2003) interviewed 137 preschoolers, 98 elementary children and their parents after a traumatic event. The dyads were asked to describe the situation and their feelings. Narrative length, elaboration, cohesion, coherence and contextual embeddedness were measured. The findings show that mothers’ and daughters’ narratives were more cohesive and coherent than fathers’ and boys’ recollections 8 Discrepancies 9 of the event. It was also determined that mothers and daughters are similar for all accounts measured, especially with older daughters. Fathers’ narrative styles were not highly correlated with either daughters or sons. This study showed that mothers and daughters had more agreement and cohesion than fathers and sons. Coffman et al. (2006) was a follow-up to the Fullerton Longitudinal Study begun in 1979, following 130 infants and their parents. At the 15-16 year old wave, parents were given the Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI) to test their relationship perceptions. The PCRI measures satisfaction with parenting, involvement, communication, limit setting and autonomy. At the same time adolescents were given several questionnaires about their relationship with their parents. The results showed that mother-adolescent perceptions are valid and reliable while father-adolescent relationships lack correspondence of perception. This study showed that mothers and adolescents are fairly congruent in their perceptions of the mother-child dyad relationship while fathers are less reliable. Miller-Johnson et al. (1994) followed 88 children who were between the ages of 8 and 18, as well as their parents, and looked at how parental-adolescent relationships impacted diabetes management. The Parent-Child Scales (PCS) were used to measure the parental perspectives of their relationships with their adolescents. The different categories measured were warmth, discipline, conflict and behavioral support. The results of this study showed that parent-child dyad relationships are correlated with diabetes management, especially in terms of conflict. Parent-child conflict is correlated with poor adherence to diabetes care. If a parent and child have a lot of conflict, the child is at risk for poor diabetes adherence resulting in poor health. This study shows how the parent child relationship is important in diabetes care in adolescents. Discrepancies 10 The studies reviewed in this section show how important parent-child congruency is for the care and management of diabetes. As seen in Miller-Johnson et al. (1994), parent and child conflict correlates with poor diabetes care. It is important for parents and adolescents to be in agreement for the best diabetes management. Both Coffman et al. (2006) and Peterson et al. (2003) show that mother-child dyads are more reliable and indicative of congruence. These studies, along with others discover that the mother-daughter dyad is more likely to be congruent than any other type of dyad. For this research study, it is important to note this trend and to analyze the data to determine if gender plays a role in the correlations. Method Design In this descriptive, correlational design I compared and contrasted parental and adolescent survey responses to determine where the congruencies were in their responses. I looked at the answers from both questionnaires given to both parents and adolescents to determine if discrepancy trends can be seen across both measures. I calculated bivariate correlations to determine if the adolescents’ gender or age had an affect on the discrepancy scores. Two different discrepancy scores were calculated for each questionnaire to show both the direction of the discrepancy and the magnitude of the within-dyad differences. I also looked at the HbA1c baseline levels of the teenagers to determine whether congruency between dyad responses has any relation to blood glucose levels. The variable of child’s age was also analyzed in the correlations to determine what effect, if any, age has on discrepancy and/or HbA1c levels. Finally, gender was correlated with the discrepancy scores and HbA1c to analyze whether males or females were more likely to be discrepant with their parents and how that impacted diabetes self-management. Discrepancies 11 Participants The participants for the study were recruited through the Vanderbilt Eskind Diabetes Clinic which is part of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee1. Adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 who had been diagnosed with Type I diabetes for at least the past six months were eligible to participate. A total of 115 adolescent-parent dyads participated in this study by completing two questionnaires. The average age of the adolescents was 15 years old with a standard deviation of 1.5. Of the adolescents that participated, 63 were males, 51 were females and there was missing data on gender for one person. Adolescents had a mean HbA1c level of 8.8% with a standard deviation of 1.76%. All but a couple of the parents were moms. Measures Parents and adolescents were asked to fill out a number of questionnaires dealing with diabetes barriers, problem solving and self-management. Both members of the family dyad were given two of the same surveys: the Diabetes Behavior Management Survey (DBMS; Iannotti, 2006), and the Problem Solving Behaviors Survey, a new measure created for this research. Both questionnaires were filled out online. The DBMS, attached as Appendix G, had 41 questions where 39 of them were answered by clicking “never”, “seldom”, “half”, “usually” or “always”. This questionnaire measured how frequently the adolescents carried out necessary self-management tasks, such as checking blood glucose, dosing insulin, and counting carbohydrates. The Problem Solving Behaviors Survey, attached as Appendix H, had 27 questions with a response option of “never”, “seldom”, “half”, “usually” or “always”. This questionnaire measured the ability of adolescents to deal with self-management problems associated with their diabetes and diabetes care. The questionnaires given to both parents and 1 This research study was part of a larger study conducted by Dr. Shelagh Mulvaney. Discrepancies 12 adolescents differed only in who was being addressed. Adolescents were asked questions about themselves and parents were asked to answer questions about their child. Procedures Only data from adolescent-parent dyads that completed both questionnaires were analyzed. The statistical software, SPSS, was used to calculate the degree of discrepancy between the parent and adolescent responses to both questionnaires. First of all, mean scores were calculated for the parents and the adolescents for both surveys, producing four separate scores: parent self-management (Psm), child self-management (Csm), parent problem solving (Pps), and child problem solving (Cps). These scores were calculated by taking the mean of the responses for each questionnaire. Discrepancy scores were calculated two separate ways to strengthen the research. Simple discrepancy scores were calculated by subtracting the child mean from the parent mean for each item on each questionnaire. Two variables were created: a simple discrepancy score for the DBMS (D_sm) and a simple discrepancy score for the problem solving survey (D_ps). Squared discrepancy scores were also calculated, creating two additional variables, a squared self-management discrepancy score (D2_sm) and a squared problem solving discrepancy score (D2_ps). The squared discrepancy scores were calculated by squaring the simple discrepancy score for each item for each survey and then were summed across the items. In all, four discrepancy variables were calculated for each dyad2. The simple discrepancy scores showed the direction of the discrepancy through the magnitude and direction of the values. The range of possible scores for the simple discrepancy variables was from -4 to 4. Highly positive simple discrepancy scores mean the parent rates 2 After exploring the data through box plots, it was determined that subject number 117 had an extreme D_sm score on the self-management study and subject number 120 had an extreme D2_ps score on the problem solving survey. In order to account for these extreme outliers, both scores were recoded as missing data. Discrepancies 13 the child more positively than the child rates him/herself. Highly negative simple discrepancy scores mean the reverse. The second discrepancy scores were the simple discrepancy scores squared for each item and then summed over the items. These scores highlighted the magnitude of the discrepancy. The formula for these scores was: d^2= (mean parent scoremean child score)^2 for each dyad. These scores were labeled as D2_sm, the squared discrepancy score for the self-management survey, and D2_ps, the squared discrepancy score for the problem solving survey. The range of possible scores for the squared discrepancy variables was from 0 to 16. The higher the squared discrepancy score, the greater the discrepancy within the dyad, regardless of which family member was higher or lower than the other. Also, by squaring each item’s simple discrepancy score, items with more disagreement contributed more to the total squared discrepancy score. Correlations using the Pearson Product-Moment Correlation were calculated between the different discrepancy scores and with other factors, including child age, gender and A1c levels. A1c Levels were measured in order to determine the adolescents’ control of their diabetes. A1c levels show the average blood glucose levels an adolescent has over the course of 8-12 weeks. Therefore, this test is one of the best indicators available of diabetes control. Results Even though the focus of this thesis was on the discrepancy scores, the first analysis examined the correlations between HbA1c and each of the separate scores on the two instruments. Scores were calculated for both the parents and the adolescents for each questionnaire yielding four scores: parent self-management (Psm): child self-management (Csm): parent problem solving (Pps): and child problem solving (Cps). The mean scores for each of the questionnaires were correlated using the Pearson Product- Moment Correlation with one another and with the child’s A1c levels. As seen in Table 1, only the child’s problem Discrepancies 14 solving score was significantly related to A1c levels (r = -0.21, p < 0.05). The more the adolescents felt they could solve diabetes-related problems, the better their glycemic control (i.e., the lower their A1c value). None of the other three scores were significantly correlated with A1c values. As also seen in Table 1, the four scores were also highly correlated with each other. Psm was significantly correlated with Csm (r = 0.53, p <0.01), meaning that the more children felt they were managing their diabetes, the more their parents thought so as well. A similar correlation occurred between Pps and Cps (r = 0.41, p < 0.01) showing that the more children thought they were solving diabetes-related problems, the more their parents agreed. Psm was also significantly correlated with Pps (r = 0.60, p < 0.01) meaning that the more parents thought their adolescents were controlling their diabetes, the more they thought the children were using problem solving skills to solve their diabetes-related problems. The same is true for the correlation between Csm and Cps (r = 0.51, p < 0.01) which shows that the more adolescents thought they were in control of their diabetes, the more they thought they could use problem solving skills for diabetes-related problems. These results show how the questionnaire responses were correlated with each other. Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations between the four different discrepancy scores and A1c values. A1c levels did not correlate with any of the discrepancy scores; however certain discrepancy scores correlated with each other. The simple discrepancy in selfmanagement correlated with the simple discrepancy in problem solving (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), and the squared discrepancy in self-management was significantly correlated with the squared discrepancy in problem solving (r = 0.36, p < 0.01). These correlations show that, with both of the discrepancy scores, if parent-child dyads were discrepant on one questionnaire, they were more likely to be discrepant on the other questionnaire as well. It also shows that both Discrepancies 15 discrepancy scores were measuring different aspects of discrepancy because they were not significantly correlated with each other. In other words, the simple discrepancy score for selfmanagement did not correlate with the squared discrepancy for self-management, and the same was the case for problem solving. Correlations were also run between the four discrepancy variables and the children’s ages and gender. Gender was coded as male (0) or female (1) and ages ranged from 13 to 18 years old. Child’s age was not significantly correlated to any other variable. Gender, however, was significantly correlated to the simple discrepancy score for problem solving (r = 0.20, p < 0.05). When the child was female, she was more likely to be discrepant from her parent on the problem solving questionnaire. Gender was also significantly correlated with the squared discrepancy score for self-management (r = -0.26, p < 0.01). This result shows that, when using squared discrepancy scores instead of simple discrepancy scores, males are significantly more discrepant from their parents on self-management than are females. Discussion This study was designed to look at the discrepancy between parent and child survey responses to see if they related to adolescent self-management of diabetes. HbA1c levels were used to measure diabetic control. As determined by the studies in the introduction, parentchild communication is a key factor in adolescent management of diabetes. Adolescents that keep their parents informed and involved are more likely to have better diabetic control. This study used discrepancy scores to measure parent-child communication. It was predicted that the higher the discrepancy between the parent-child dyads, the higher the blood glucose levels. Two different types of discrepancy scores were calculated and analyzed to determine their relationships to each other and to A1c, child’s age, and gender. It was also predicted that parent-child dyads with high discrepancy scores on one of the instruments (either self- Discrepancies 16 management or problem solving) would also be discrepant on the other instrument. Furthermore, it was predicted that discrepancy scores would be associated with higher HbA1c values. No hypotheses were stated for the relationships between discrepancy scores and child age or gender. Those analyses were purely exploratory. This study aimed to determine if parent-child discrepancy affected self-management of the adolescents’ diabetes. It was predicted that high amounts of discrepancy between parents and their children would lead to poor diabetic control. First, the mean simple scores for the parents and children for each survey (Psm, Csm, Pps, and Cps) were correlated with A1c. Results show that the Cps score correlated with A1c levels. This shows that the children’s responses to the problem solving questionnaire were correlated with blood glucose levels. This result is important because it shows that the adolescent’s self-report of problem solving behaviors is related to their diabetic control in terms of A1c. Correlations were then run with the four discrepancy variables and it was determined that A1c levels were not correlated significantly with any of the discrepancy scores. Another main focus of this study was to look at different ways to measure discrepancy between parent and adolescent responses to the same surveys. Two separate variables were used to measure this discrepancy for each survey. The simple discrepancy scores, D_sm and D_ps were important because they show the direction of the discrepancy through signs. A negative discrepancy meant that the child scored him/herself higher on the survey questions than did his/her parent. The second discrepancy score calculated was a squared discrepancy, D2_sm and D2_ps, and these variables were important because they magnified the discrepancy for each dyad. Dyads with small amounts of discrepancy on an item-by-item basis had squared discrepancy scores that stayed relatively small and dyads with large discrepancy became even larger. The different discrepancy scores for each survey were not Discrepancies 17 significantly correlated, meaning the correlations between D_sm and D2_sm and between D_ps and D2_ps were not significant, so it can be concluded that they measure different aspects of discrepancy and so they are both important to use when trying to determine discrepancy scores. While the two different discrepancy variables for each survey were not correlated with each other, the different types of discrepancy variables across surveys were correlated with each other. Both simple discrepancy variables were correlated and both squared discrepancy scores were correlated. This shows that dyads were discrepant across surveys. If a parentchild dyad had a high discrepancy on one survey, on average, they had a high discrepancy on the other survey as well. Gender also played a role in discrepancy scores. The results, depicted in Table 3, show that females had, on average, higher discrepancy between their responses and their parents on the problem solving survey. Results also showed that males were significantly more discrepant on the squared discrepancy score for the self-management survey. Males and their parents were more likely to disagree on self-management behaviors. It is important to note that problem solving is an internally driven response that is harder to analyze by other people. It is generally easier for parents to know their child’s self-management behaviors than their problem solving behaviors. During the difficult transition to self-management during adolescence, parents should still monitor their child’s care and be involved in some way. It is very important, especially during this time, to help the adolescent develop and stick to a care regimen that they can use to help make the transition to self management easier. Discrepancies 18 Limitations This study has several limitations in regards to the participants. All participants were recruited through the Vanderbilt Eskind Diabetes Clinic which is part of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. While there were 115 families that participated, it may not be representative of the overall population of adolescents with type I diabetes. A parent of the adolescent also participated in the study and in this case, almost all parents were female. Fathers were not really represented in this study. It is hard to tell how these limitations affected the overall study, but it is necessary to account for them. Another limitation of the study was that there are many other variables that may impact A1c levels. Blood glucose levels measure more than diabetic self-management, including hormonal changes, and it is difficult to isolate one variable. Calculating significant correlations using A1c levels can be hard with so many factors playing a role. Future Research Several important questions remain after completing this study that will require future research. One big question is what other factors determine self management? It would be important to look at what else plays a role in diabetes care, more specifically in selfmanagement. It is also important to research other ways to measure self-management of diabetes, other than HbA1c levels. If self-management could be measured in more ways than A1c, the results of this study would be enhanced. In order to determine the reliability and validity of the different discrepancy variables, it is important to utilize these measurements in other studies. Future studies looking at discrepancy should calculate the different scores to see if they are correlated. It would be important to make sure that these discrepancy scores were still separate measurements, both add unique aspects and different ways to look at discrepancy. This study is the first to use Discrepancies 19 both formulas to measure discrepancy so it is necessary to make sure the results duplicate in other studies. Conclusion This study measured different aspects of parent-child discrepancy in order to determine how discrepancy impacted self-management of diabetes. Diabetes management was measured using baseline A1c levels of the adolescents. Correlations showed that A1c levels were not correlated with any the discrepancy scores, however it was correlated with the child problem solving score. This means that adolescents who ranked themselves highly on the Problem Solving Behaviors Survey had better glycemic control. This shows how important it is for adolescents transitioning into self-management of their diabetes to learn and be able to use problem solving techniques. Children that can successfully handle diabetes related problems have better control. The results of this study showed that the discrepancy scores correlated amongst each other. It was determined that if a dyad was highly discrepant on one survey, they were likely to be discrepant across both. This finding shows that parents and adolescents are consistent with discrepancy across both surveys. It is important that parents and children be on the same page in terms of diabetes care and self-management. While this study did not find predicted correlations with A1c levels, it did show that it is important to measure the different aspects of discrepancy. Both discrepancy scores looked at the congruency between parents and children from different points of view. This study determined that different types of discrepancy scores can be useful when analyzing different parts of discrepancy by focusing on direction of discrepancy and magnitude. Discrepancies 20 References Anderson, B.J., Ho, J., Brackett, J., Laffel, L.M.B. (1999). An office based intervention to maintain parent-adolescent teamwork in diabetes management. Diabetes Care, 22(5), 713-721. Berg, C.A., Wiebe, D.J., Beveridge, R.M., Palmer, D.L., Korbel, C.D., Upchurch, R., et al. (2007). Mother-child appraised involvement in coping with diabetes stressors and emotional adjustment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(8), 995-1005. Coffman, J.K., Guerin, D.W., Gottfried, A.W. (2006). Reliability and validity of the parentchild relationship inventory (PCRI): evidence from a longitudinal cross-informant investigation. Psychological Investment, 18(2), 209-214. Dugdale, D.C. (2009). HbA1c. Medline Plus. Retrieved September 2009; <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003640.htm>. Ellis, D.A., Podolski, C.L., Frey, M., Naar-King, S., Wang, B., Moltz, K. (2007). The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: impact on regimen adherence in youth with Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(8), 907-916. Iannotti, R.J., Nansel, T.R., Schneider, S., Haynie, D.L., et al. (2006). Assessing regimen adherence of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 29(10), 2263-2270. Lewandowski, A., Drotar, D. (2006). The relationship between parent-reported social support and adherence to medical treatment in families of adolescents with Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(4), 427-436. McDougal, J. (2002). Promoting normalization in families with preschool children with type I diabetes. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses, 7(3), 113-120. Miller-Johnson, S., Emery, R.E., Marvin, R.S., Clarke, W., Lovinger, R., Martin, M. (1994). Parent-child relationships and the management of insulin-depemdemt diabetes Discrepancies 21 mellitus. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 603-610. Peterson, C., Roberts, C. (2003). Like mother, like daughter: similarities in narrative style. Developmental Psychology, 39(3), 551-562. Stallwood, L. (2005). Influence of caregiver stress and coping on glycemic control of young children with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Heath Care, 19(5), 293-300. Stark, P.B. (2010). Scatterplots. SticiGui Statistics. Berkeley, CA. Retrieved 18 March 2010. < http://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Java/Html/ScatterPlot.htm>. Discrepancies 22 Table 1. Pearson Product-Moment Correlations Between the Individual Scores and A1c A1c A1c 3 Pps4 Correlation N 113 -.141 1 .168 -.211* .026 .405** .000 1 112 99 114 -.128 .604** .314** .214 .000 .002 96 97 97 98 Correlation -.083 .341** .555** .534** Sig. (2-tailed) .382 .001 .000 .000 N 112 98 113 97 Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) Correlation N 1 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). 3 The A1c variable is the baseline HbA1c blood glucose levels of the adolescents. The Pps variable is the mean parent scores across items on the Problem Solving Behaviors Survey. 5 The Cps variable is the mean child scores across items on the Problem Solving Behaviors Survey. 6 The Psm variable is the mean parent scores across items on the DBMS Survey. 7 The Csm variable is the mean child scores across items on the DBMS Survey. 4 Csm 99 Sig. (2-tailed) Csm7 Psm 97 N Psm6 Cps 1 Sig. (2-tailed) Cps5 Pps 1 114 Discrepancies 23 Table 2. Pearson Product-Moment Correlations Between the Discrepancy Scores and A1c A1c A1c Correlation D_sm D_ps D2_sm D2_ps 1 Sig. (2-tailed) N D_sm8 Correlation -.042 Sig. (2-tailed) .686 N D_ps9 99 Correlation .057 .455** Sig. (2-tailed) .581 .000 97 98 99 Correlation .080 .057 -.073 Sig. (2-tailed) .433 .576 .474 98 99 99 100 Correlation -.060 -.039 -.124 .360** Sig. (2-tailed) .564 .702 .225 .000 96 97 98 98 N D2_ps11 1 97 N D2_sm10 113 N 1 1 1 98 **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). 8 The D_sm variable is the simple discrepancy scores between parent-adolescent dyads across items on the DBMS Survey. 9 The D_ps variable is the simple discrepancy scores between parent-adolescent dyads across items on the Problem Solving Behaviors Survey. 10 The D2_sm variable is the squared discrepancy scores between parent-adolescent dyads across items on the DBMS Survey. 11 The D2_ps variable is the squared discrepancy scores between parent-adolescent dyads across items on the Problem Solving Behaviors Survey. Discrepancies 24 Table 3. Pearson Product-Moment Correlations Between the Discrepancy Scores, A1c, Child’s Gender and Age A1c D_sm D_ps D2_sm D2_ps Gender Childs Age A1c Pearson 1 Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N D_sm Pearson 113 -.042 1 Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N D_ps .686 97 99 .057 .455** .581 .000 97 98 99 .080 .057 -.073 .433 .576 .474 98 99 99 100 -.060 -.039 -.124 .360** .564 .702 .225 .000 96 97 98 98 98 .145 .126 .199* -.258** .015 Sig. (2-tailed) .126 .217 .050 .010 .882 N 112 98 98 99 97 114 Pearson .018 -.041 .046 -.032 -.056 .046 Sig. (2-tailed) .847 .685 .656 .752 .585 .630 N 112 98 98 99 97 114 Pearson 1 Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N D2_sm Pearson 1 Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N D2_ps Pearson 1 Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N Gender Pearson 1 Correlation Childs Age 1 Correlation **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). 114 Discrepancies 25 Appendix A Individual Score Means and Standard Deviations N Psm Csm Pps Cps 98 114 99 114 Valid N (listwise) 96 Minimum Maximum 2.76 2.88 2.35 2.04 4.53 4.62 4.23 4.62 Mean Std. Deviation 3.7418 3.7115 3.2955 3.4710 .34933 .38066 .44612 .52297 Discrepancies 26 Appendix B Discrepancy Score Means and Standard Deviations N D_sm D_ps D2_sm D2_ps 99 99 100 98 Valid N (listwise) 97 Minimum Maximum -1.03 -1.62 .27 .50 1.06 1.04 3.19 4.85 Mean Std. Deviation .0318 -.1863 1.3401 2.4036 .34927 .52716 .62791 .91009 Discrepancies 27 Appendix C Histogram for D_sm Variable Discrepancies 28 Appendix D Histogram for D_ps Variable Discrepancies 29 Appendix E Histogram for D2_sm Variable Discrepancies 30 Appendix F Histogram for D2_ps Variable Discrepancies 31 Appendix G Diabetes Behavior Management Survey( DBMS) Discrepancies 32 Discrepancies 33 Discrepancies 34 Discrepancies 35 Discrepancies 36 Discrepancies 37 Discrepancies 38 Discrepancies 39 Discrepancies 40 Appendix H Problem Solving Behaviors Survey Discrepancies 41 Discrepancies 42 Discrepancies 43