Proposal Science in the Context of

advertisement

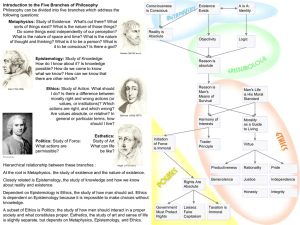

Proposal page 1 Kevin D. McMahon Student ID#: 78513 SED 600 April 3, 2007 Proposal Science in the Context of The True, The Good, and The Beautiful The National Research Council reported in How People Learn that perhaps the single most important distinction between experts and novices is the formers’ ability to perceive the “big ideas” of their domains. Their [experts] knowledge is not simply a list of facts and formulas that are relevant to their domain; instead, their knowledge is organized around core concepts or “big ideas” that guide their thinking about their domains. (National Research Council, 2000 p.36) This allows them to conditionalize new knowledge, facilitate retrieval of existing knowledge, and apply knowledge in new and creative ways (NRC, 2000). The NRC encouraged that curricula be developed that will facilitate students to organize knowledge around Big Idea themes (NRC, 2000). Big Idea themes become the paradigms of specific scientific domains (Kuhn, 1996); for example, evolution has become the paradigm for the biological sciences, atomic theory for chemistry, and plate tectonics for geology. “To have knowledge but without being able to use it in new and different ways is akin to not having knowledge at all.” (Kaplan, 2007) To use scientific knowledge in “new and different ways” requires transference to other domains. Part of the difficulty Proposal page 2 that students experience is in moving from “determinant” zones of K-12 education to “indeterminant zones of practice” (Schön, 1987 p.6) in which students must navigate into real-world problems that are ill-defined, lacking required information, and not having a well-defined end state (Fortus, 2005). Transference can be facilitated if students recognized that science is not a separate domain operating with its own set of rules in complete isolation from the rest of human experience. Rather, science exists within the Big Idea theme of epistemology—the branch of philosophy that considers how we know and criteria of truth. But epistemology exists within an even larger idea that interconnects it with ontology (the branch of philosophy that considers the nature of being) and ethics (the branch of philosophy that considers how we are to act). Plato introduced this Trivium to philosophy in his dialogues with the Good (ethics), the True (epistemology), and the Beautiful (ontology). Science informs and is informed by the Trivium of which it has become an integral component. Purpose Statement The purpose of the proposed research is to examine what, if any, benefits students may receive from knowledge of the interrelationship between science and the Trivium. Can knowledge of the Trivium: (1) facilitate an understanding of the Nature of Science by comparing and contrasting it to other ways of knowing? The term “trivium” was used to describe the medieval curriculum that included grammar, logic and rhetoric. The original Latin meaning of trivium is “where three roads meet” which is appropriate here because in the Platonic sense the three roads of ontology, epistemology, and ethics meet in the realm of human experience. Proposal page 3 (2) provide students with an appreciation for the strengths and limitations of science as it contributes to our ontological and ethical understanding of the world, ourselves, and the communities in which we live? (3) allow students to integrate a scientific world view that respects their personal, family and cultural/religious experiences? (4) promote students’ perception of the interconnectedness of all knowledge? (5) facilitate transference between science and other academic domains? (6) and foster the development of the virtue of wonderment? Importance of the Study What is the purpose of education? Is it job training? Yes, but it is hopefully more than a good income, a nice car, and a house in a gated community (although this is often the carrot that teachers dangle in front of students to motivate them to study and do their homework). Education is also about providing student with the knowledge and the tools of inquiry from which they can begin to construct a worldview—one which may be uniquely theirs yet consistent with the American ideals of rights and responsibilities. Yet, for many if not most students science, math, language, and social studies, along with their cultural and perhaps religious traditions, are disparate fields of knowledge for which they are ill equipped to construct a harmonious view of themselves and the communities in which they are a part. Senseless violence, sexual promiscuity, drug abuse, difficulty in establishing committed relationships, worship of celebrity with its concomitant emphasis on materialism and fame may be evidence of a failure to construct a viable worldview. Is the Trivium a panacea to these problems? No. Will it help? History suggests it might. Proposal page 4 Western civilization was, in part, built upon a synthesis of Athens and Jerusalem: the Good, the True, and the Beautiful with sin, the Law and redemption. While separation of Church and State may preclude Jerusalem it does not forbid entry into Athens and the benefits that may be obtained from the study of philosophy. Definition of Terms Term Epistemology Ethics Materialism Ontology Scientism Trivium Definition the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of knowledge, in particular its foundations, scope, and validity. a system of moral principles governing the appropriate conduct for an individual or group. the theory that physical matter is the only reality and that psychological and spiritual phenomena will eventually be explained as physical functions. the branch of philosophy concerning the nature of being; includes metaphysics. the belief that science alone can explain phenomena, or the application of scientific methods to fields unsuitable for it. the three main branches of philosophy as defined by Plato in his dialogues: the True (epistemology), the Good (ethics), and the Beautiful (Ontology) and how together they create Big Ideas or paradigms. Literature Review The Nature of Science and the Trivium Epistemology There has been an increased recognition for the need of incorporating the Nature of Science into science curriculum. Explicit instruction on the Nature of Science and “real science experiences” for teachers and students would do much to dispel the “mist of Proposal page 5 half-truths” that prevent students from appreciating “both the strengths and limitations” of science (McComas, 1997 pp 53,68). Misconceptions persist regarding the nature of science “due to a lack of philosophy of science content in teacher education” (McComas, 1997 p.53). But misconceptions regarding the limitations of science are evident even among scientists who clearly believe that science as an epistemological endeavor is not limited or has no need to be informed by other ways of knowing. This is usually based upon the assumption of ontological materialism: If all that is is matter than science as the method par excellence for studying matter becomes the method par exellence for knowing all there is to know. We take the side of science in spite of the patent absurdity of some of its constructs, in spite of its failure to fulfill many of its extravagant promises of health and life, in spite of the tolerance of the scientific community for unsubstantiated just-so stories, because we have a prior commitment, a commitment to materialism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counterintuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. (Lewontin, 1997) Assumptions of materialism does not make good science, rather it is a form of scientism which St. Pierre defines as follows: Scientism means science's belief in itself: that is, the conviction that we can no longer understand science as one form of possible knowledge, but rather must identify knowledge with science (St. Pierre, 2006 p.259) Scientism is naïve at best, epistemological chauvinism at its worst and potentially dangerous when it draws from its conclusions a code of behavior for individuals and society. Proposal page 6 Ethics Epistemology does not stand-alone—it is inevitably linked to and informs ethics. Those that see science as epistemologically superior to all other forms of knowing will likely conclude that it should also be the touchstone upon which our ethics should be based. "The continuing challenge is to make our ethics as good as our science.” (Churchill, 2002) “Let us ensure that our bioethics are as sophisticated as our science.” (NAS 1996 p. 111) However, given the comments of some scientists (see below) one has to wonder whether or not science should be the sole arbiter of our ethical judgments. "No newborn infant should be declared human until it has passed certain tests regarding its genetic endowment, and that if it fails these tests it forfeits the right to live.” — Dr. Francis Crick, Nobel Prize Laureate 1962, codiscovery of DNA. "Chimeras [human-animal crossbreads] or parahumans might legitimately be fashioned to do dangerous or demeaning jobs. As it is now, low-grade work is shoved off on moronic and retarded individuals, the victims of uncontrolled reproduction. Should we not program such workers 'thoughtfully' instead of accidentally, by means of hybridization?" — Dr. Joseph Fletcher, Harvard University professor widely recognized as the "patriarch of bioethics" "If you are really stupid, I would call that a disease...so I'd like to get rid of that....People say it would be terrible if we made all girls pretty. I think it would be great." — Dr. James Watson, president of the Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory, New York, Nobel Prize Laureate, co-discovery of DNA. (as cited from Elliot Institute, 2006) If there is more to ethics and the “good life” than what can be defined scientifically than we have to foster respect for other ways of knowing in our classes. As Professor of Education, Elizabeth St. Pierre, has stated: Proposal page 7 The science I value acknowledges that there are different truths (but not that “anything goes”) and that our task as scientists should be to produce different knowledge and produce knowledge differently in order to enlarge our understanding…. What I cannot imagine stands guard over everything that I must/can do, think, live insist that I engage, rather than exclude, other epistemologies and the other who claims them in order to move toward the unthought. (St. Pierre, 2006 p.260) There is also ample research that suggests that our students could benefit from explicit instruction in ethics. The research of Troy Sadler (2004) demonstrated that when students were presented with ethical dilemmas they did not demonstrate any particular systematic approach to their decision making process. A recent survey of American Youth conducted by the Josephson Institute of Ethics (2006) revealed that: • • • • • • 82% admit they lied to parent within the past year about something significant. 62% admit they lied to teacher within the past year about something significant. 60% cheated during a test at school within the past year. 23% stole something from a parent or other relative within the year. 19% stole something from a friend within the past year. 28% stole something from a store within the past year. These statistics may not be surprising to those of us that work with young people, but what is truly disturbing is that this same survey revealed that 92% of the students surveyed stated that they were “satisfied with my own ethics and character.” Clearly, these young people can be characterized as ethical novices. What they lack is a Big Idea which the NRC states is necessary to move from novice to expert. The Big Idea used to be provided by the various faith communities, but as we move towards an increasingly secular society ethics has become disengaged from its religious structures. Freed from these ontological and epistemological moorings ethics has devolved into a form of lazy self-interested pragmatism and in some instances nihilistic hedonism. What does this have to do with science education? Proposal page 8 Science is often characterized as morally neutral—perhaps it is, but scientists are not. Henriikka Clarkeburn demonstrated that those trained in the sciences did not demonstrate an increased moral sensitivity to socio-scientific moral issues compared to comparably educated college students (Clarkeburn 2003). Yet, we are entrusting our scientists with perhaps the greatest moral issues of our time—the manipulation of the human genome. We can expect that the generation of scientists we are now training will have even greater complex moral dilemmas to confront. There is cause for concern when one considers that these future scientists are derived from the same stock that admitted to lying, cheating, and stealing but were okay with there own moral development. If we are serious about moving our students from being ethical novices to experts we need to give some space to ethical discussion in our science curricula while providing students a framework by which to respectfully engage moral dilemmas and those who hold varying opinions. Ontology In his essay, A Thing of Beauty, Arthur Miller tells a story that turns scientific epistemology and its claim that “the experiment is king” on its head: In Schrödinger’s first attempt to concoct his famous wave equation, he looked for one that agreed with relativity theory. The equation he came up with, however, was not supported by experiment. Eventually he produced the Schrödinger equation, which was not beautiful, but did at least fit the data. Dirac thought that Schrödinger should have ignored the data and persevered in his pursuit of a beautiful equation. Dirac did just that. He discovered an equation that was consistent with relativity theory but represented in a mathematics unfamiliar to most physicists…. The problem was that it predicted particles with negative energy, which everyone thought was an impossibility. Werner Heisenberg condemned it as the “saddest chapter in theoretical physics.” Shortly afterwards, Dirac realized that these particles were actually antiparticles with positive energy. They were later discovered in the laboratory. Once again insisting on beauty in a mathematical theory revealed unexpected features in nature. (Miller, 2006) Proposal page 9 Dirac is not alone on his insistence that aesthetics should be fundamental to how we do science. Nobel Laureate, Richard Feynman observed, “You can recognize truth by its beauty and simplicity.” (Augros, 1984) Should aesthetics become a part of science education? Some science educators believe that it should. Mitchel Resnick from MIT had students incorporate aesthetical principles in the construction of laboratory instruments. His conclusion was that students were more committed to the discovery process when they were encouraged to design their equipment to be beautiful (Resnick, 2000) Beauty represents a unifying principle of ontology. This beauty is not in the eye of the beholder, rather it represents the harmonious interplay between the One and the Many—a concept that works readily with science: cells tissues organs, or the laws of thermodynamics that extends to the Many of biology, chemistry, and physics. Aesthetical principles such as these can provide students with a Big Idea that may facilitate their conditionalizing, retrieving and applying of knowledge. The Virtue of Wonderment Francis Bacon, often credited with being the father of modern science, gave us the axiom, Scientia est potentia—Knowledge is power. This is suggestive of a utilitarian approach to science. But Bacon possessed a loftier ambition: "Nay, the same Solomon the king, although he excelled in the glory of treasure and magnificent buildings, of shipping and navigation, of service and attendance, of fame and renown, and the like, yet he maketh no claim to any of those glories, but only to the glory of inquisition of truth; for so he saith expressly, "The glory of God is to conceal a thing, but the glory of the king is to find it out;" as if, according to the innocent play of children, the Divine Majesty took delight to hide His works, to the end to have them found out; and as if kings could not obtain a greater honour than to be God's playfellows in that game...." Proposal page 10 This is an expression of wonderment. Wonder comes from the Old English word, wundor, which meant a "marvelous thing, marvel, the object of astonishment" (Harper, 2001). This is the mind’s response to beauty and it is an ethical stance of humility towards the transcendent evident within the immanent. It is an acknowledgement of the limitations of our epistemologies and of the inherent mystery of things. It is the wisdom to stop probing with our methodologies and instruments, if only for a moment, in order to listen and allow things to reveal themselves as they are. Wonderment recognizes that we, as knower, and the object of our knowing, are as Bacon might put it, “purified through the vexation of inquiry.” (Pesic, 1999 p.81) Wonderment transforms the “power” of knowledge to humble service to nature and humanity. Relevance to the Reseda High School Science Magnet, Its Students, and Myself Since its inception the RHS Science Magnet has had a tradition of matriculating its graduating seniors to some of the finest universities in the country. This year’s graduates will be going to Stanford, Yale, Berkeley, Harvard, and yes, even CSUN (yeah, I’m a Matador—’77)! Our students will go on to become leaders in their fields. The RHS Science Magnet is participating in the shaping of our nation’s future and I, as part of its faculty, have played a modest part. As I enter the latter stages of my career I find myself increasingly concerned not just about empowering my students with knowledge but in expanding the ways in which they perceived that knowledge can be legitimately “Although many writers state that Francis Bacon advocated the torture of nature in order to force her to reveal her secrets, a close study of his works contradicts this claim. His treatment of the myth of Proteus depicts a heroic mutual struggle, not the torture of a slavish victim. By the "vexation" of nature Bacon meant an encounter between the scientist and nature in which both are tested and purified .” Proposal page 11 acquired, and how a variety of knowing can provide a more holistic understanding of our universe, one another, and ourselves. This, I believe, can introduce students to the virtue of Wonderment. If, in some small measure, the Trivium could facilitate students perception of the universe, each other and themselves as “marvelous things” and “objects of astonishment” then this Action Research project would have been worth the effort. Method The objective of my Action Research project is to determine whether or not students can benefit (as defined on page 3) by an exposure to the Trivium in their chemistry class. The project’s methodology will include explicit instruction (web-based & class discussion), activities, pre and post assessments and a survey. Teaching science and philosophy has given me the opportunity to interconnect seemingly disparate fields. Inevitably, I drew from my knowledge of one domain to help me teach the other. I developed a concept map, A Model of the Human Atom, to help my students (who had had me previously for biology and/or chemistry) understand the similarities and differences between the various philosophical systems (realism, nominalism, empiricism, rationalism, existentialism, etc.). They all told me that it helped them understand philosophy, but what surprised me was that many of them told me that it helped them with their literature, history, and even their science and math classes. What follows, therefore, is a brief description of the model. An atom consists of a nucleus surrounded by orbitals and suborbitals which contain pairs of electrons spinning in opposite directions. The Model of the Human Atom Proposal page 12 proposes an analogous arrangement with the human nucleus surrounded by three hexagonal orbitals: ontology, epistemology, and ethics (the Trivium). Each of these hexagonal orbitals has six suborbitals that contain a pair of antinomies. The human nucleus remains undefined in this model because it is highly personalistic in that it is shaped by the individual’s faith, philosophy, and life-experiences. The illustration below shows an overview of the model (for more detail go to www.csun.edu/~kdm78513 and click on the sun). I propose developing this model into a web-based instructional unit where each component of the concept map is hyperlinked to a brief lesson. Students will be instructed to access the site, complete the unit which will also incorporate a short assessment. The following day there will be a brief discussion of the material assigned during the class warm-up. It is anticipated that explicit instruction of the model will be Proposal page 13 limited to approximately ten minutes/day so as to not significantly interfere with course instruction. Prior to the introduction of this model students will be given a Pre-test. The focus of the pre-test will be to assess the students’ knowledge of the philosophical ideas that will be discussed in the Model, their attitudes towards the relevancy of these ideas, and to present them with “scientifically-based” scenarios that will have them explore the relationship between science, epistemology, ontology, and ethics. In addition to the explicit instruction provided by the web-based instructional unit and the warm-up discussions I plan to provide three activities. Since I plan to conduct the Action Research during my introductory units in chemistry (which include Atomic Theory) these activities will focus on the development of our models of the atom. The table below summarizes the activities, and their relationship to the model and Trivium: Activity 1. Mendeleev and the Periodicity of the Elements 2. Schrödinger and Durac: Pursuit of the Beautiful 3. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Focus/Objective Nature of Science and Epistemology Ontology and Epistemology Science/Epistemology and Ethics These “transfer” activities will provide students the opportunity to relate the scientific principles we discussed in class and philosophical concepts they were exposed to through the Model of the Human Atom. At the conclusion of the Action Research project the student will take a Post-test which may be the same as the Pre-test. They will also complete a survey that will examine the students’ attitudes about the information and process they experienced during the project. I anticipate collecting various forms of data that will include (1) pre-tests, (2) web-based assessments, (3) graded activities, (4) post-test, and (5) final survey. I suspect Proposal page 14 that some of this data may need to be coded. It is anticipated that this will provide me with sufficient data for triangulation so that a conclusion can be drawn regarding project’s objective. Timeline Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Objective Pre-Test/Introduction to the Trivium & the Model of the Human Atom NOS/Epistemology: Precision/Accuracy, Authority/Method NOS/Epistemology: Apriori/Aposteriori, Intuition/Reason NOS/Epistemology: Kataphatic/Apophatic, Personal/Communal Activity: Mendeleev and the Periodicity of the Element Ontology: One/Many, Stability/Mutability Ontology: Order/Chaos, Design/Chance Ontology: Something/Nothing, Transcendent/Immanent Activity: Schrödinger and Durac: Pursuit of the Beautiful Ethics: Good/Evil, Fallen/Evolved Ethics: Self/Other, Freedom/Determinism Ethics: Natural/Positive Law, Virtues/Values Activity: Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Post-Test/Survey Closing Remarks Finally, there is the question as to whether students would be even interested in a philosophical approach to learning science. Do they care about such esoteric themes as aesthetics, criteria of truth, or the natural law versus evolutionary ethics? I recently conducted an Internet survey of the student at Reseda Science Magnet pertaining to this question. One hundred and nine students (approximately ¼th of the Magnet student body) participated in the survey. The results are summarized below: 1. Believe that ethical issues should be discussed in science class. 2. Believe that how science “knows” should be a more significant part of science class. 3. Is interested in discussions that include the relationship between science and religion. 4. Believe that learning aesthetics and ontology could be helpful to their study of science. 5. Is interested in learning about how science and philosophy can together help create a Big Picture. Agree 68.8 Disagree 14.7 No Opinion 16.5 82.6 6.4 11 61.5 19.2 19.3 56 18.4 25.7 85.3 6.4 8.3 Proposal page 15 6. Believe that such a Big Picture would help them learn 84.4 science. 7. Would be interested in taking a class dedicated to these 75.2 topics. Click here for Complete Survey Result (pdf) 6.4 8.3 11.1 13.8 The results clearly indicate that students are not only interested in such Big Idea topics as Ontology, Epistemology, and Ethics but believe that it can help them learn science as well. Students can be overwhelmed with seemingly disparate factoids. There is ample education research to suggest that students can move from novices to experts when they can conditionalize these factoids into a comprehensible Big Ideas. I have suggested that this Big Idea should exceed specific subject domains to incorporate a conceptual network of ontology, epistemology, and ethics. I believe this can facilitate students moving from novices to “accomplished novices,” as the NRC observed: A model that assumes that experts know all the answers is very different from a model of the accomplished novice, who is proud of his or her achievements and yet also realizes that there is much more to learn. (NRC, 2000 p50) Perhaps the most important thing that can happen for the student while conditionalizing new knowledge to a Big Idea is the acquisition of the virtue of intellectual humility, that awareness that regardless of the level of expertise acquired one always remains, at best, an accomplished novice. References Augros, R. & Stanciu, G. (1984) The New Story of Science. Lake Bluff, Ill. Regnery Gateway. Churchill, L (2001) The News & Observer. Retrieved April 3, 2007 from Proposal page 16 http://gazette.unc.edu/archives/01apr11/file.18.html Clarkeburn, H. (2003) Measuring Ethical Development in Life Science Students: a study using Perry’s developmental model. Studies in Higher Education Vol 28, No. 4 October, 2003 p. 444-456 Elliot Institute (2006) In Their Own Words. Retrieved April 3, 2007 from http://www.elliotinstitute.org/mad.htm Fortus, D. (2005) Design-based science and real-world problem-solving. International Journal of Science Education. Vol 27, No.7. 3 June 2005 pp.855-879 Harper, D. (2001) Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved April 22, 2007 from http://www.etymonline.com Josephson Institute (2006) Josephson Institute Report Card on the Ethics of American Youth: Part One—Integrity Retrieved November 18, 2006 from http://www.josephsoninstitute.org/reportcard/ Kaplan, S. (2007) Conference: Differentiated Instruction in Science and Math. Van Nuys, CA January 19, 2007 Kuhn, T. (1996) The Structures of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago. University of Chicago Press Lewontin, R. (1997) Billions and Billions of Demons The New York Review Vo. 9 January 1997 p.31 McComas, W. (1998) The Nature of Science in Science Education. Dordreck. Kluwer Academic Miller, A. (2006) A Thing of Beauty. New Scientist, Vol. 189, Issue 2537 National Research Council (2000). How People Learn (Expanded Ed) Washington D.C. National Academy Press NAS (1996) 2020 Vision: Health in the 21st Century. Retrieved on April 3, 2007 from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=5202&page=108 Pesic, P. (1999) Wrestling with Proteus: Francis Bacon and the "Torture" of Nature. Isis, Vol. 90, No. 1 (Mar., 1999), pp. 81-94 Resnick, M., Berg, R. & Eisenberg, M. (2000) Beyond Black Boxes: Bringing Transparency and Aesthetics Back to Scientific Investigation. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 9(1), 7- 30. Proposal page 17 Sadler, Troy D (2004) Moral Sensitivity and its Contribution to the Resolution of SocioScientific Issues. The Journal of Moral Education Vo. 33, No. 3, September 2004 St. Pierre, E. (2006) Scientifically Based Research in Education: Epistemology and Ethics. Adult Education Quarterly. Vol. 56 No. 4 pp. 239-266