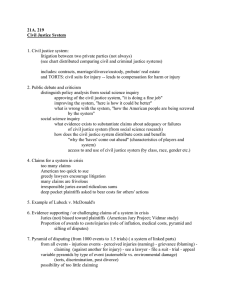

Issacharoff Miller

advertisement