Court Politics: Where We Are and Where We May be Headed Under President Bush

advertisement

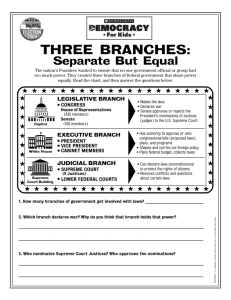

22nd Stetson University College of Law Annual National Conference on Law and Higher Education THE FUTURE OF HIGHER EDUCATION LAW IN THE U.S. SUPREME COURT PART I SUPREME COURT POLITICS: WHERE WE ARE AND WHERE WE MAY BE HEADED UNDER PRESIDENT BUSH Lawrence White* Program Officer The Pew Charitable Trusts Philadelphia, Pennsylvania February 19, 2001 Introduction Late in the evening of December 12, 2000, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Bush v. Gore, the case that effectively decided last year’s Presidential election.1 Confused television viewers watched while reporters struggled to make sense of 65 pages’ worth of concurring and dissenting opinions. It took the better part of an hour for the bottom line to emerge: the Court, by a vote of 5 to 4, had ended the recount of contested ballots in Florida and given George W. Bush the narrow electoral vote majority he needed to win the election. Never before in the nation’s history had a federal court been so intimately involved in the election of a President. To some, including Justices on the Court, the decision in Bush v. Gore sounded the crescendo in an anguished national debate over the appropriate boundaries of judicial involvement in the political process. In a widely quoted passage, Justice John Paul Stevens concluded his dissenting opinion with these words: The … [decision by] the majority of this Court can only lend credence to the most cynical appraisal of the work of judges throughout the land. It is confidence in the men and women who administer the judicial system that is the true backbone of the rule of law. Time will one day heal the wound to that confidence that will be inflicted by today’s decision. One thing, however, is certain. Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s Presidential election, the identity of the * The views expressed in this paper are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of The Pew Charitable Trusts. 1 121 S. Ct. 525, 2000 U.S. LEXIS 8430 (2000). -2- loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation's confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.2 In the aftermath of the decision, academic experts and commentators wondered whether the Court had done lasting damage by injecting itself so directly into the political process. Echoing Justice Stevens’ words, New York University Law School Professor Seth Harris said in a newspaper interview that “the Supreme Court has succeeded in finding a way that everyone loses. Gore loses the case and the election. Bush loses the opportunity for the legitimacy of the recount and the clear mandate of a unified Supreme Court decision. And the Supreme Court loses a substantial chunk of its credibility. It is the worst possible outcome to a very difficult case.”3 Others scoffed: “Although there will doubtless be claims of partisanship in the high court's decision,” wrote University of Denver Law School Professor Robert Hardaway, “50 years from now this decision will be remembered not for its technical arguments relating to election law and equal protection, but rather for the fact that it finally ended a fiercely contested election dispute that was threatening to dissolve into political and social chaos.”4 The purpose of my presentation is to set the stage for Professor Rahdert’s discussion of the Supreme Court and higher education law by providing a glimpse into the all-too-human dimensions of the Court, its Justices, and the processes by which the Court is likely to be reshaped during the Bush presidency. A year ago I might have undertaken the assignment sheepishly, wondering whether the politics of the Court would seem trivial or irrelevant. But after Bush v. Gore, there’s no need to pretend that the Court makes law without a weather eye to the political implications of its work – or that elected officials appoint or confirm Supreme Court Justices without considering their political proclivities. Once upon a time Mr. Dooley could poke fun at the Supreme Court for following the election returns, but now the commingling of political and judicial functions has come to be perceived, cynically or otherwise, as an important 2 2000 U.S. LEXIS 8430 at 50-51. “National Expert: Court’s Decision Made Losers of Us All,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, December 14, 2000, p. 22A. 3 4 “Bush vs. Gore: Legal Experts Dissect Supreme Court Decision and Its Long-Term Effects,” Denver Rocky Mountain News, December 17, 2000, p. 1B. -3dimension of Supreme Court jurisprudence and we live with the fact that the Court doesn’t just follow the election results – it determines ’em. I. A Supreme Court Primer The United States Supreme Court is established by Article III of the United States Constitution and is the ultimate decision-making body in the federal judicial system. The Court consists of nine Justices: the Chief Justice of the United States and eight Associate Justices.5 Members of the Court are appointed by the President and confirmed by the United States Senate. “To ensure an independent Judiciary and to protect judges from partisan pressures, the Constitution provides that judges serve during ‘good Behaviour,’ which has generally meant life terms.”6 The Supreme Court is a court of limited jurisdiction. Unlike, for example, a state trial court, which is generally required to adjudicate any case filed in its clerk’s office, the Supreme Court hears only the cases it chooses to hear – and it selects only a minuscule proportion of filed cases to hear and decide on the merits. Parties who wish to have their cases heard by the Supreme Court file a petition – technically known as a petition for writ of certiorari – with the Court. In the 1999 Term – the Term that started in October, 1999, and ended in the summer of 5 Students of American history know that the number of Associate Justices is fixed, not by the Constitution, but by federal statute. The number could conceivably be increased or decreased by legislative fiat. In 1937, President Roosevelt, persistently frustrated by a conservative majority of Supreme Court Justices opposed to New Deal legislation, proposed a “judicial reorganization bill” that would have enabled the President to appoint an additional Justice for every sitting Justice aged 70 or older – a measure that would have expanded the Court to as many as 13 Justices. Before Congress could act on the proposed legislation, however, the Supreme Court in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379 (1937), reversed one of its earlier rulings and upheld the legality of minimum-wage legislation, handing the Roosevelt Administration a major victory. The Court’s decision in West Coast Hotel was instantly branded “the switch in time that saved nine,” and commentators as well as Congressmen recognized that the decision “clearly signaled the Court’s acceptance of the main features of the New Deal.” Kermit L. Hall, William M. Wiecek & Paul Finkelman, AMERICAN LEGAL HISTORY: CASES AND MATERIALS 487 (1991). Roosevelt’s Court-packing legislation died quietly during the summer of 1937, and nobody has seriously suggested since that the number of Associate Justices be changed from the current eight. This passage is from the Supreme Court’s official Web site – www.supremecourtus.gov/about/institution.pdf. 6 -42000 – the Court received about 7,300 petitions. The Court chose only 92 cases to hear – about 1.3 percent of the total.7 There is no appeal from the Supreme Court’s denial of a petition for writ of certiorari. The Court has unfettered discretion to select the cases it will decide, and that power is among the most significant and politically charged of those wielded by the Court.8 How, as a practical matter, does the Court decide when to grant a petition for certiorari? Rule 10 of the Supreme Court’s Rules9 sets out three broad categories of cases that the Court will, under the appropriate circumstances, accept for review: When a federal appellate court enters a decision that is “in conflict with the decision of another [appellate court] on the same important matter,” the Court may grant certiorari in one or both cases (so-called “split in the circuits” jurisdiction). When a state court or federal appellate court “has decided an important question of federal law that has not been, or should be, settled by this Court, or has decided an important federal question in a way that conflicts with relevant decisions of this Court,” then review may be granted (“important federal question” jurisdiction). The Court may accept review when a lower court “has so far departed from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings, or sanctioned such a departure by a lower court, as to call for an exercise of this Court’s supervisory power.” All three categories contain ample wiggle room (the matter has to be “important” to warrant review, and so forth). To repeat, the Court has virtually unfettered freedom to decide what cases it will hear or not hear as part of any given year’s docket of cases. II. The Justices on the Court Today Reproduced in an appendix at the end of this paper are the abbreviated biographies of the nine Justices who serve on the Supreme Court today.10 7 The Supreme Court, 1999 Term: Statistics, 114 HARV. L. REV. 390, 397 (2000). 8 See generally Robert L. Stern, Eugene Gressman & Stephen M. Shapiro, SUPREME COURT PRACTICE (6th ed. 1986), Ch. 4, Factors Motivating the Exercise of Jurisdiction, pp. 188-253. 9 www.supremecourtus.gov/ctrules/rules.pdf. 10 This biographical material is taken from the Supreme Court Web site at www.supremecourtus.gov/about/biographiescurrent.pdf -5- The Chief Justice, William Rehnquist, was originally appointed as an Associate Justice in 1972 and ascended to the Chief Justiceship in 1986, when former Chief Justice Warren Burger retired. Like Chief Justice Rehnquist, six of the eight Associate Justices (John Paul Stevens, Sandra Day O’Connor, Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, David Souter, and Clarence Thomas) were appointed to the Court by Republican Presidents. The Court’s most junior members – Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer – were appointed by President Bill Clinton, a Democrat. Table 1: Incumbent Supreme Court Justices, by Date of Appointment and Party Affiliation Justice Year Appointed By President -- Party Rehnquist 1972 Nixon Republican Stevens 1975 Ford Republican O’Connor 1981 Reagan Republican Scalia 1986 Reagan Republican Kennedy 1988 Reagan Republican Souter 1990 Bush Republican Thomas 1991 Bush Republican Ginsburg 1993 Clinton Democrat Breyer 1994 Clinton Democrat There is a tradition – which, with only a few isolated exceptions, has prevailed up to the present – of according the President broad latitude in appointing Supreme Court Justices. Since President Reagan’s contentious and ultimately unsuccessful nomination of Robert Bork in 1987, five Supreme Court nominees have been confirmed by the Senate. Only Clarence Thomas’s controversial nomination in 1991 was close. (See table at the top of the next page.) -6- Table 2: Senate Votes on Supreme Court Nominees, 1988 to Present Nominee Kennedy Souter Thomas Ginsburg Breyer Date 1988 1990 1991 1993 1994 Senate Vote 97-0 90-9 52-48 96-3 87-9 III. Some Characteristics of the Supreme Court Today In comparison to other epochs in the history of the Court, today’s Court has four unique characteristics that define it in political terms. First, it is an unusually experienced Court. The nine Justices have been on the Court for an average of fifteen years each, an unusually long time. Two Justices (Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Stevens) have been on the Court for more than a quarter of a century, and six of the nine Justices have served for ten years or more. Even before they reached the Supreme Court, eight of the nine Justices (all but Chief Justice Rehnquist) served apprenticeships as judges on the lower federal courts or state trial and appellate courts. Seven of the nine Justices, in fact, have worn judicial robes for twenty years or more; only Justice Scalia (19 years) and Justice Thomas (11 years) have been judges for less than two decades. In another respect, one pertinent to Professor Rahdert’s presentation at this conference, the Justices are very experienced: four of them (Justices Scalia, Kennedy, Ginsburg and Breyer) were full-time university faculty members prior to their appointments to the bench. Justice Scalia taught at the law schools of the University of Virginia, the University of Chicago, Georgetown University and Stanford University. Justice Kennedy spent 23 years on the faculty at the McGeorge School of Law in California. Justice Ginsburg taught for seventeen years at the law schools at Rutgers University and Columbia. Justice Breyer spent more than a dozen years on the faculty at Harvard. In comparison to Courts of the past, this one has first-hand experience in academia and presumably understands what higher education stands for and how it works. -7- But while the Justices have a great deal of experience on the bench and in the classroom, there is one respect in which they collectively lack the kind of experience members of the Court possessed in years gone by: only one Justice – Justice O’Connor – has held elective office, and none has held elective federal office. In the past, some of the most distinguished members of the Court were former United States Senators (Justice Hugo Black), former governors (Chief Justice Earl Warren), and even, once, a former President of the United States (Chief Justice William Howard Taft). Second, it is an unusually stable Court. The nine Justices who are on the Court today have served together for almost seven years – or, to make the same point in another way, it has been almost seven years since a vacancy on the Court was filled by a new Justice. Not since 1823 has the Court been through a longer period without a change in personnel. By way of comparison, between 1930 and 1990, a period of sixty years, Presidents appointed 33 new Justices, an average of one new appointee every 22 months. Third, it is an unusually – one could even say startlingly – polarized Court. It is a Court with strongly cohesive and well-defined voting blocs, and indeed one cannot fully understand today’s Court without an appreciation of the ideological divide represented by those blocs. On the left, politically speaking, are the four Justices who form the Court’s more or less dependably liberal bloc: Justices Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg and Breyer. On the right are the four Justices who form the Court’s solidly conservative bloc: Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices Scalia, Kennedy and Thomas.11 11 There are more than a few eminent commentators who classify Justice Kennedy, not as a member of the Court’s right flank, but as a swing vote. I beg to disagree, based on the statistics compiled by the HARVARD LAW REVIEW as part of its year-end summary of the Supreme Court Term. The law review calculates for each Justice a so-called “alignment quotient,” representing the frequency with which each Justice votes with each of the other Justices in full-opinion decisions. Alignment quotients can be compared to see how often particular combinations of Justices voted as a bloc. In the October 1999 Term, Justice Kennedy voted with Chief Justice Rehnquist 76 percent of the time; with Justice Thomas 62 percent of the time; and with Justice Scalia 56 percent of the time. By contrast, he voted with the members of the liberal bloc only 29 percent of the time on average. The Supreme Court, 1999 Term: Statistics, 114 HARV. L. REV. 390, 392 (2000). Although I am loathe to allow personal political views to intrude, I’m deep enough into this footnote to see if I can get away with a fleeting exception. Justices Scalia and Thomas almost always vote together; their “alignment quotient” was 90 percent last Term, close to the highest of any two Justices on -8In the middle is Justice O’Connor, who plays a remarkable role as the Supreme Court’s pivot point. The Court is so intractably divided, and Justice O’Connor’s vote is so frequently determinative of the outcome in specific cases, that as a practical matter she almost never dissents. Her vote is assiduously cultivated by advocates who argue before the Court and by the Justices themselves, who reason (often with justification) that her vote will provide the crucial fifth vote needed to cement a Court majority. Consider these statistics: Every Term, a healthy proportion of cases accepted by the Court for review are relatively uncontroversial cases that are ultimately decided by unanimous vote. In the October 1999 Terms, as in almost all past Terms, unanimous opinions accounted for more than one-third of all decisions – 42 percent, in fact, or 32 out of the 77 cases decided by written disposition. In only 45 cases did one or more of the Justices file dissenting opinions. In those 45 cases, however, 18 – 40 percent of the total – were decided by margins of 5 to 4. That’s an extraordinarily high number, reflecting the close divisions and degree of polarization among the Justices. And of those 18 cases decided by 5-4 votes, Justice O’Connor sided with the majority in 15 of them! Justice Souter, by comparison, voted with the five-member majority in only six of the 18 cases; Justice Breyer in only four; Justice Ginsburg in only three. Of the non-unanimous cases decided by the Court last Term, Justice O’Connor voted with the majority an astonishing 92 percent of the time – far more often than the next-ranking Justice (Rehnquist, at 84 percent) – and dissented in only four cases all Term, one of the lowest numbers since the HARVARD LAW REVIEW began keeping statistics more than thirty years ago. With tongue in cheek, one wag commented, “This has led efficiency experts to suggest that Court staff could be trimmed 88% if the redundant Justices were simply eliminated, leaving Justice O’Connor to decide the cases on her own.”12 the Court. Still, that was down from 97 percent in the 1996 Term, which led some observers to wonder whether Justice Thomas was becoming a more independent judicial thinker. Wrote one cynical commentator, “[Justice Thomas’s] standing in the academic community has witnessed a corresponding boost: Whereas in the past he was viewed as a dangerous extremist and Scalia clone, he is now viewed simply as a dangerous extremist.” John P. Elwood, What They Were Thinking: The Supreme Court in Revue, October Term 1999, 4 GREEN BAG 2d 27, 34 (2000). 12 John P. Elwood, What They Were Thinking: The Supreme Court in Revue, October Term 1999, 4 GREEN BAG 2d 27, 31 (2000). -9- To the consternation of some legal commentators, the rigid schisms among the Justices has had another effect besides close outcomes: it has caused palpable friction between the Justices and contributed to what many perceive as a deterioration in comity and civility at the Court. One scholar compared the Justices to “nine scorpions in a bottle” and chronicled many examples of intemperate language in dissenting opinions, scornful questioning of counsel during oral arguments, and other manifestations of interpersonal tensions in the relationships among the Justices.13 The well-known Supreme Court reporter Stuart Taylor once described the contemporary era in Supreme Court history as “the season of snarling justices,” and the phrase was quickly repeated by others writing about the Court during the Rehnquist era.14 Fourth and finally, this Court suffers from – or enjoys, depending on your viewpoint – an unusually high political profile. In the last decade, to an extent unprecedented in its history, the Court has been the subject of sustained, intense, and often far from flattering attention from the media. The Court has been in the spotlight because of – 13 Justice Thomas’s nationally televised and highly controversial face-off against Anita Hill during his confirmation hearing in the summer of 1991; Chief Justice Rehnquist’s role as presiding officer during the Senate impeachment trial of President Clinton in 1998 and 1999; The emergence of the Supreme Court and several individual Justices as issues during the 2000 Presidential election campaign15; and Phillip J. Cooper, BATTLES ON THE BENCH: CONFLICT INSIDE THE SUPREME COURT 173 (1995). Stuart Taylor, “Season of Snarling Justices,” Akron [Ohio] Beacon Journal, April 5, 1990, page A11, cited in, e.g., Christopher E. Smith, The Supreme Court in Transition: Assessing the Legitimacy of the Leading Legal Institution, 79 KY. L. J. 317, 329 n. 56 and accompanying text (1991). 14 During the summer of 2000, Republican candidate George W. Bush, in answer to a reporter’s question, described Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas as the Justices he most admired, and promised that his appointees to the Court would fit their conservative mold. Democratic candidate Al Gore pounced on the issue during one of the televised Presidential debates, saying in answer to a question about Supreme Court appointments: “[T]he next president is going to appoint three, maybe four Justices of the Supreme Court. And Governor Bush has declared to the antichoice groups that he will appoint Justices in the mold of Scalia and Clarence Thomas who are known for being the most vigorous opponents of a woman’s right to choose.” “Supreme Interest: For Some Justices, The Bush-Gore Case Has a Personal Angle,” Wall Street Journal, December 12, 2000, page A1. 15 -10- The unprecedented attention paid to the Supreme Court’s two decisions in the Florida Presidential election dispute in December, 2000.16 The predictable result is that, more loudly than we might have expected (or than many astute observers of the political scene believe is healthy), the Court has become the object of rancorous partisan finger-pointing. The Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore, reported Newsweek Magazine, “exposed the raw undercurrent of politics that runs beneath [the Justices]. Their actions sullied the naive but necessary faith in their Olympian neutrality. In pulling the legal fire alarm, we may have set the fire station ablaze – with high courts just another set of institutions cuffed around in the hardball culture.”17 IV. The Supreme Court Tomorrow: Who Might Go? Whom Might President Bush Appoint? By contemporary standards, the nine Supreme Court Justices are collectively old – but not that old. When President Carter assumed office in 1977, the nine Justices then on the Court averaged slightly less than 64 years of age. Almost a quarter-century later, when President George W. Bush was sworn in, the nine Justices were an average of just over 66 years old – not a pronounced increase over a period during which the average life expectancy for American males increased by almost six years and for American females by more than four years. 18 During the Carter presidency, no Supreme Court Justices left the bench. We cannot and should not assume that President George W. Bush will have vacancies to fill any time soon, or possibly at all. 16 For access to the complete texts of court decisions and briefs in the interrelated cases constituting the Florida Presidential election dispute, see the “Florida Election Cases” page on the Supreme Court Web site – www.supremecourtus.gov/florida.html. “Disorder in the Courts: Judicial Rollercoaster: Bush vs. Gore is Headed Back to the U.S. Supreme Court. Will the Fierce Legal Battles Finally Get Us a New President and End the Chaos--or Ignite a Constitutional Crisis?”, Newsweek Magazine, December 18, 2000, page 26. 17 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nat’l Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Report, 47:28 (December 13, 1999), Table 12, “Estimated Life Expectancy at Birth in Years, by Race and Sex,” www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/pdf/47_28t12.pdf. 18 -11- Still: There are some differences between the Court now and the Court in 1977. For one, the Carter Court had only one Justice who was more than 69 years old; today’s Bush Court has three, including one Justice (Stevens) who is in his 80s. For another, the Justices on the Court today may not be as healthy, collectively, as those who served two decades ago. Two of the Justices on the Court today (O’Connor and Ginsburg) are cancer survivors, and two (Rehnquist and O’Connor) have had disabling back problems in the past. Finally, some Court watchers speculate that partisan rancor among the Justices may take its toll in either or both of two ways: it may fatigue one or more battle-weary Justices to the point where they might consider retiring, and it may prompt conservative Justices to retire during the incumbency of a conservative President who could presumably be trusted to appoint ideologically sympathetic replacements. Some compare the situation today to the one that existed in 1993, when the newly elected Democratic President, Bill Clinton, inherited a politically divided Court that had one Justice in his eighties (Justice Harry Blackmun, then 84), two in their seventies (Justices Byron White, then 75, and Stevens, then 72), and an average age of 63. In the first two years of President Clinton’s first term, two Justices retired (Blackmun and White) and were replaced by Clinton appointees (Ginsburg and Breyer). At any rate, most observers of the Court, including at least one of the Justices, speculate that President Bush may have two, three, or even four vacancies to fill in the next few years.19 The Justices most likely to leave the Court are widely assumed to be – Justice O’Connor. At age 70, she is not in good health and may be ready to return to her home in Arizona. In a story widely picked up by other media, the Wall Street Journal reported in December that Justice O’Connor’s husband, at a private dinner party on election day, “mentioned to others [his wife’s] desire to step down” if a Republican were elected President.20 19 “No less an authority than Justice Thomas recently mused publicly that the next president would ‘certainly’ get to fill some vacancies.” Charles Lane, “Chance for Change Makes High Court a Rallying Point, Washington Post, November 5, 2000, page A6. “Supreme Interests: For Some Justices, the Bush-Gore Case Has a Personal Angle,” Wall Street Journal, December 12, 2000, page A1. Newsweek Magazine subsequently carried a florid account of the dinner party attended by Justice O’Connor and her husband on election day: 20 Supreme court justice Sandra Day O'Connor and her husband, John, a Washington lawyer, have long been comfortable on the cocktail and charity-ball circuit. -12 Chief Justice Rehnquist. A member of the Court for 29 years and Chief Justice for the last 14, he is 76 years old and in constant pain from a chronically bad back. If he were to remain on the Court until the end of President Bush’s current term, he would at that point be one of the oldest men ever to serve as Chief Justice and would have served longer than any Chief in almost a century. Justice Stevens. Although he is the oldest of the currently serving Justices, he “boasts of beating opponents half his age at tennis”21 and may not be ready for ideological reasons to retire, but few Justices have served into their mid-80s. Justice Ginsburg. She is approaching 70 and spent much of last year undergoing chemotherapy and radiation treatment for recently diagnosed colon cancer. Whom would President Bush select if he were to have one or more vacancies to fill on the Supreme Court? The answer depends to some extent on which Justice’s retirement creates the vacancy. Political considerations might intrude. For example, if Justice O’Connor or Justice Ginsburg were to leave, there might be pressure on the President from some quarters to appoint a woman to fill that vacancy. Similarly, a vacancy in the Chief Justiceship might get caught up in So at an election-night party on Nov. 7, surrounded for the most part by friends and familiar acquaintances, she let her guard drop for a moment when she heard the first critical returns shortly before 8 p.m. Sitting in her hostess's den, staring at a small black-and-white television set, she visibly started when CBS anchor Dan Rather called Florida for Al Gore. “This is terrible,” she exclaimed. She explained to another partygoer that Gore's reported victory in Florida meant that the election was “over,” since Gore had already carried two other swing states, Michigan and Illinois. Moments later, with an air of obvious disgust, she rose to get a plate of food, leaving it to her husband to explain her somewhat uncharacteristic outburst. John O'Connor said his wife was upset because they wanted to retire to Arizona, and a Gore win meant they'd have to wait another four years. … Two witnesses described this extraordinary scene to Newsweek. Responding through a spokesman at the high court, O'Connor had no comment. “The Truth Behind the Pillars,” Newsweek Magazine, December 25, 2000, page 46. 21 Tony Mauro, “One New Justice May Tip Court,” USA Today, August 23, 2000, page 15A. And see Charles Lane, “Chance for Change Makes High Court a Rallying Point, Washington Post, November 5, 2000, page A6: “[Justice] Stevens is in vigorous health, has arranged a schedule that permits him to spend ample time at a vacation home in Florida and enjoys certain prerogatives on the court by virtue of being the senior associate justice. A former law clerk who met with the justice recently came away convinced that Stevens showed no signs of losing interest in his work. ‘He still gets a charge out of it,’ the former clerk said.” -13- political cross-currents; at least a few commentators have identified Antonin Scalia as an eager candidate to replace William Rehnquist as the Court’s next Chief Justice, and given thenGovernor Bush’s words of praise for Justice Scalia during the campaign that idea may not be farfetched.22 These caveats aside, what can we predict today about the kinds of candidates President Bush might nominate for Supreme Court vacancies, the reception those nominees might receive on Capitol Hill, and the impact new members might have on the fragile political and judicial dynamics of a divided Court? In no particular order, here are four observations on the future of the Supreme Court under the new President. First, many close observers predict that President Bush’s first appointment to the Court will be Hispanic. There has never been a Hispanic Supreme Court Justice. As one long-time Supreme Court reporter wrote during the campaign, “if there is a vacancy on the Supreme Court, for the first time a Hispanic-American will be nominated, or at least seriously considered. Carlos 22 I must pause here to relate one of the more delightful anecdotes from the 2000 campaign. During the last few months of the campaign, Vice President Gore hammered away at his opponent for identifying Justice Scalia as one of the members of the Supreme Court whom he admired most. At an annual conference on the Supreme Court held at the College of William and Mary in the fall of 2000, the tarttongued dean of Supreme Court correspondents, Lyle Denniston of the Baltimore Sun, reported on some investigative digging he had done to determine when and under what circumstances Governor Bush had first proclaimed his admiration for Justice Scalia. It turned out that the Governor had appeared many months before on the NBC news show “Meet the Press.” He and host Tim Russert engaged in the following colloquy, during which the Governor revealed that he did not know Justice Scalia’s first name and appeared not to have a clue about his record on the Court: Russert: Which Supreme Court justice do you really respect? Bush: Well, that’s – Anthony [sic] Scalia is one. Russert: He is someone who wants to overturn Roe v. Wade. Bush: Well, he’s a – there’s a lot of reasons why I like Judge [sic] Scalia. … He’s an unusual man. He’s an intellect. The reason I like him so much is I got to know him here in Austin when he came down. He’s witty, he’s interesting, he’s fun. There’s a lot of reasons why I like [him]. The colloquy is reproduced in Michael McGough, “Supreme Speculation,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 1, 2000, page E1. I will leave to others the task of identifying potential Supreme Court nominees who meet the new President’s criteria that they be “interesting” and “fun.” -14- Ortiz of the Hispanic National Bar Association, who has lobbied patiently for the nomination of a Hispanic to the Supreme Court for more than a decade, says, ‘It is impossible to imagine that the next nominee will not be a Hispanic…. We have waited too long.’”23 The first name uttered by most knowledgeable speculators is that of Texas-based federal appellate judge Emilio Garza, who was appointed to the trial court by President Reagan and elevated to a seat on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals by President Bush’s father. Garza, 53 years old, is a law-and-order judge known as a no-nonsense criminal sentencer. He is also firmly opposed both to abortion and to the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence in abortion-related cases, and he generated controversy four years ago when he used a concurring opinion in a high-profile legal challenge to a Louisiana parental-notification statute to declare his personal belief that the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade was “inimical to the Constitution.”24 As far as other potential Bush nominees are concerned, media speculation has focused on the same short list of potential candidates, most of whom are conservative federal appellate judges appointed to the bench by President Reagan or the first President Bush. The list includes: Michael Luttig of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, a 45-year-old described in one press report as “the most conservative judge on the most conservative federal appeals court in the nation.”25 Chief Judge Pasco Bowman of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals in Kansas City, a protégé of Senator Jesse Helms. 23 Tony Mauro, “One New Justice May Tip Court,” USA Today, August 23, 2000, page 15A. 24 Causeway Medical Suite v. Ieyoub, 109 F. 3d 1096, 1113 (5th Cir. 1997) (Garza, J., concurring). Just a few months ago, in what appeared to some as an overt attempt to burnish his conservative reputation with the incoming Bush administration, Judge Garza dissented from a Fifth Circuit decision vacating the capital murder conviction of a man sentenced to die for a triple slaying at a Houston bowling alley. The defendant, a former mental patient and self-described drug addict, initially confessed to shooting three men in the head during a botched robbery attempt. By a vote of 2-1, the Fifth Circuit reversed a jury conviction, ruling that the defendant’s right to counsel had been violated when police officers questioned him immediately after his arrest. In a toughly worded dissent, Judge Garza asserted that the conviction should have been affirmed because the defendant, while in police custody, “simply failed to request counsel in an unequivocal manner.” Soffar v. Johnson, 2000 U.S. App. LEXIS 33526, at 149 (December 21, 2000) (Garza, J., dissenting). Bill Rankin, “Move to Right Seems Certain – Expect Backlash If Any Bush Nominees are Seen as Too Conservative,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 17, 2000, page G6. 25 -15- Judge Edith Jones of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Houston, 51 years old, a law-and-order judge with a reputation as a proponent of the death penalty. Judge Samuel Alito, Jr., 50 years old, a member of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals in Newark, New Jersey, whose conservative leanings are so pronounced that he has been called “Judge Scalito” because of his opinions’ resemblance to those of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.26 Judge Jerry Smith of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Houston, 53 years old, a strong opponent of litigation against cigarette manufacturing companies. Chief Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Charlottesville, Virginia, 56 years old, a noted conservative intellectual. Also mentioned for a possible Supreme Court appointment later in President Bush’s term is Attorney General and former United States Senator John Ashcroft. Second, we can glean some possible insights by examining the justices George W. Bush appointed to the Texas Supreme Court while he was Governor of that state. In his six years as Texas Governor, George W. Bush appointed five of the nine members of the Texas Supreme Court. His appointees included two women, one Hispanic, and no African-Americans.27 As a group, they are young (mostly in their 40s and early 50s), and come from corporate and largelaw-firm backgrounds. Most of them have long-time ties to Bush family members and business enterprises. As judges, they have received mixed reviews. One leader of the Texas bar characterized them as “Christian-right, pro-police conservatives.”28 Others, however, have observed that the Court, to the dismay of some of the Governor’s Texas supporters and presumably the Governor himself, has proven to be more supportive of abortion rights than many 26 Id. 27 The Bush appointees are James A, Baker (appointed in 1995), Greg Abbott (1996), Deborah G. Hankinson (1997), Harriet O’Neill (1998), and Alberto R. Gonzales (1999). Their biographies are available online at www.supreme.courts.state.tx.us. Judge Gonzales left the bench two months ago to become Counsel to President Bush. Gaylord Shaw, “Diverging Views on Court: Supreme Tests for Bush, Gore,” Newsday, September 11, 2000, page A4. 28 -16- anticipated. On March 22, 2000, just as the Presidential primaries were at their zenith, the Texas Supreme Court, by a vote of 6-3, voted to reverse a trial court decision in a closely watched parental notification case and ruled that a young, pregnant minor was sufficiently mature to make her own decision about terminating her pregnancy without notifying one of her parents. Four of the six members of the majority were Bush appointees.29 Third, it is possible, maybe even probable, that the nomination of a new Supreme Court Justice would unleash a partisan confirmation fight of such ferocity that it would make the World Wrestling Federation SmackDown look tame by comparison. The close split among the Justices and the large number of 5-4 decisions suggest that the appointment of even one new member could make a portentous difference in the balance of political and philosophical power on the Court. The high stakes are amplified by the narrowness of the Republicans’ hold on the Senate, the willingness of emboldened Senate Democrats to use parliamentary and delaying tactics against conservative nominees, and frayed Congressional nerve endings in the aftermath of the bitterly (and endlessly) contested presidential election last year. One other factor is worth noting. Supreme Court nominations are acted upon in the first instance by the Senate Judiciary Committee. As we saw during last month’s hearing on John Ashcroft’s nomination to be Attorney General, the Judiciary Committee is populated by caustic, sharp-elbowed veterans of political trench warfare. Of all the standing committees in the Senate, none is as bitterly divided along partisan and ideological lines as Judiciary. The eight Republican members are among the Senate’s most conservative, and the eight Democratic members are considerably to the left of the Democratic mainstream. Among the most venerable of the various scales used to rate the comparative liberal (or conservative) voting records of Senate members is one compiled each year by the liberal lobbying group Americans for Democratic Action (ADA). Senators are rated on a scale from zero to 100, with zero meaning that a particular Senator did not adopt the liberal position on a single key vote and 100 meaning that the Senator supported the liberal position every time. In 2000, the eight Republicans who currently serve on the Judiciary Committee had an average ADA rating of 6.9 out of 100. The eight Democrats’ 29 In re Jane Doe 4, 19 S. W. 3d 322 (Texas 2000). -17- average rating was an astonishing 97.5 out of 100. Six Republicans had scores of zero, and four Democrats had scores of 100.30 Table 3: ADA Ratings of Senate Judiciary Committee Members, 2000 Senator State Score Senator State Score Republicans: Hatch Thurmond Grassley Specter Kyl DeWine Sessions Smith Utah South Carolina Iowa Pennsylvania Arizona Ohio Alabama New Hampshire 0 0 0 40 0 10 0 5 Democrats: Leahy Kennedy Biden Kohl Feinstein Feingold Torricelli Schumer Vermont Massachusetts Delaware Wisconsin California Wisconsin New Jersey New York 95 95 95 100 100 100 95 100 It’s a committee, in short, that isn’t afraid to cast partisan votes and doesn’t shy away from bareknuckled politics in the consideration of Presidential nominees to the federal judiciary. Finally, and as a good segue to Professor Rahdert’s presentation, the alteration of even a single vote on today’s Court could presage seismic shifts in Supreme Court jurisprudence in the immediate future. Some of the most provocative issues on the social agenda – abortion rights, affirmative action, Eleventh Amendment and sovereign immunity, the right to be protected from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation – were all the subjects of 5-4 decisions during the 1999 Term. The addition of even a single new Justice could create a new majority on either the right or the left of the Court, and two or more new Justices would almost certainly rearrange the existing voting blocs. 30 These data and the numbers in Table 3 are taken from an interesting Web site maintained by Dr. George Watson, a professor at Arizona State University. The Web site, called “A Vacancy on the Court,” can be found at http://rodan.asu.edu/~george/vacancy.