09RTTT CCR2012

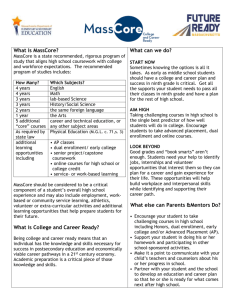

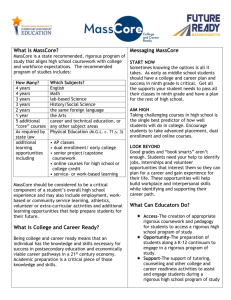

advertisement