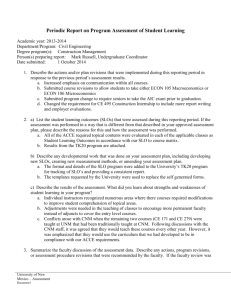

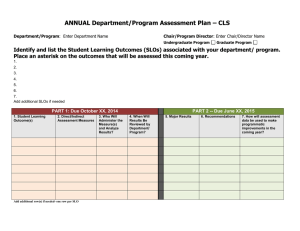

CNM Handbook for Outcomes Assessment (doc)

advertisement