Informationsheets_6.14_dm.pptx

advertisement

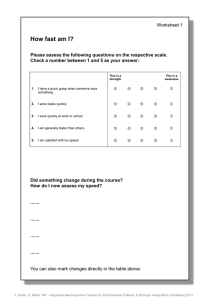

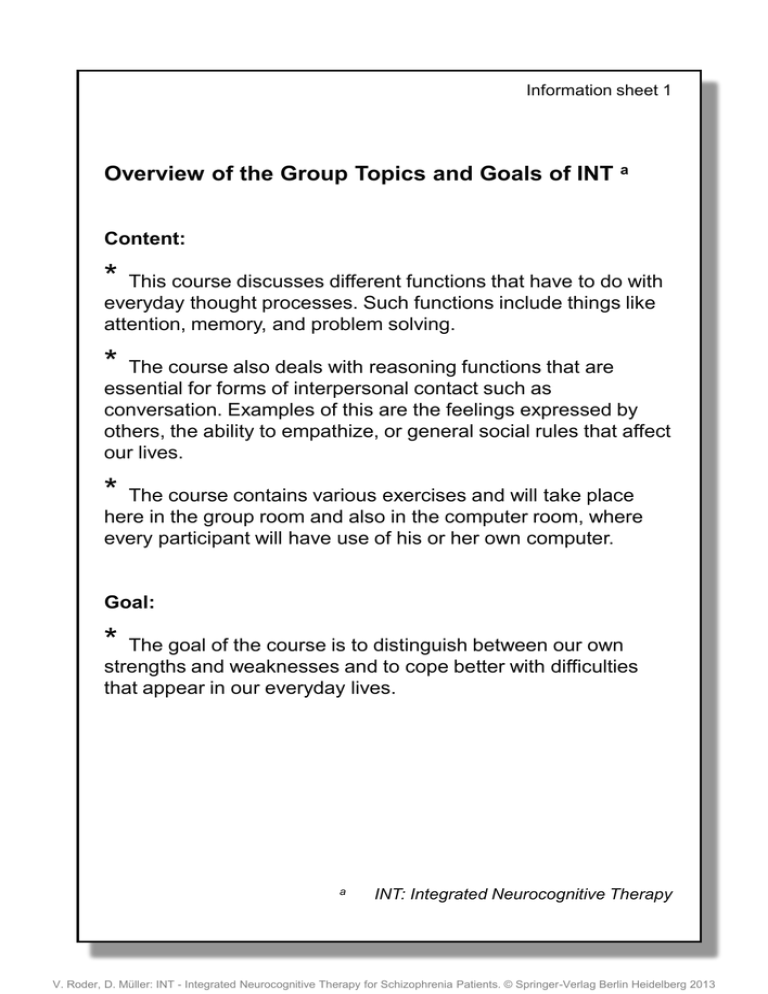

Information sheet 1 Overview of the Group Topics and Goals of INT a Content: * This course discusses different functions that have to do with everyday thought processes. Such functions include things like attention, memory, and problem solving. * The course also deals with reasoning functions that are essential for forms of interpersonal contact such as conversation. Examples of this are the feelings expressed by others, the ability to empathize, or general social rules that affect our lives. * The course contains various exercises and will take place here in the group room and also in the computer room, where every participant will have use of his or her own computer. Goal: * The goal of the course is to distinguish between our own strengths and weaknesses and to cope better with difficulties that appear in our everyday lives. a INT: Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 2 Performance and Mood Our mood depends on how tense we feel. Our mood and level of tension affect our performance in everyday reasoning and action. The activation chart below illustrates this relation: Activation Chart Ability to cope in everyday life high low Mood: bored, disinterested, depressed, tired, lacking energy, interest, and motivation ... Consequences: lack of challenge inactivity/withdrawal Low performance medium Mood: motivated, interested, alert, self-confident, feeling well, ... Consequences: positively challenged actively goal-oriented High Performance high Tension (Activation) Mood: anxious, insecure, annoyed, nervous, distrustful, the feeling of losing control ... Consequences: excessive challenge overactivity Low performance V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 3 How do I become faster and more attentive? The following strategies for improvement have proved effective: Direct influence on speed and attention: * Repeated practice: so that the activity to be performed becomes a simple routine ("Practice makes perfect"). * Prevent distraction: concentrate on the task at hand, repeatedly visualize the goal and content of the activity (say sentences like "My task is to ..." or "I want to concentrate only on my task" or write down the goal and content of the present activity). * A break at the right time: a short, but intensive period of work followed by a break ("I want and am now allowed to give myself a short break"). * Motivate yourself: plan on doing something pleasant or rewarding yourself somehow after finishing the activity. *Reducing fear of the activity: start with simple activities that we feel confident about. Divide the task into subtasks and orient yourself by them ("in the next quarter of an hour I have the following goal"). * .... Preventative measures (indirect influence): * Increasing alertness: develop motivation and interest for the target activity. * * Sufficient rest: regular sleep and life rhythm. .... V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 4 The Influence of Sleep Quality and Lifestyle A good quality of sleep is the most important requirement for health, wellbeing and concentration. Fatigue during the day is related to a poor quality of sleep at night. The term sleep hygiene refers to life habits that promote healthy sleep. Important requirement for good sleep include healthy living and good nutrition. Keeping just a few "rules" helps most people experience more restful sleep. * Caffeine: Caffeinated drinks such as coffee, tea, and cola as well as prescription and non-prescription medications containing caffeine should generally not be consumed three to four hours before bedtime. * Nicotine: Nicotine is also a stimulant, which disturbs sleep and can interrupt a good night's sleep as a result of withdrawal. Cigarettes and some medications contain considerable amounts of nicotine. Smokers who give up their habit fall asleep faster and wake up less often during the night as soon as their withdrawal symptoms are overcome. * Alcohol: Alcohol reduces brain activity. While the consumption of alcohol before bed does help to fall asleep initially, it ultimately leads to sleep interruptions. A "nightcap" before going to bed can lead to waking reactions, nightmares, and morning headaches. * Sports: Regular sports activities promote sleep. While athletic exertion in the morning does not negatively affect sleep at night, the same exertion can disturb sleep if performed within too short a time interval before bedtime. * Sleeping environment: A comfortable bed and a dark room are important requirements for good sleep. A cool, but not cold room and fresh air are helpful. Disturbances such as strong light sources in the bedroom can be eliminated easily, e.g. with dark curtains or dim light. Noise disturbances can be reduced with the help of low-volume background music or ear plugs. * Nutrition: Full meals shortly before going to bed should be avoided just as well as excessive and poorly digestible meals during the day, since such consumption can lead to difficulties falling asleep or staying asleep. Milk and all milk products contain the sleep-promoting substance tryptophan, so they are ideal for a small evening meal. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 5 How can I concentrate better at work? Having to concentrate on a task at work for a longer period of time can be very tiring, especially if the activity is dull. When we get tired, we start to take "pseudo-breaks" which lead to distraction and reduction of concentration. For this reason, it is important that we take breaks consciously so that we can maintain energy and concentration. The following types of useful breaks have proven effective: * interruptions: duration about 2030 seconds, do not leave the work location, useful for structuring one's work: - stretch (neck, back, legs, arms) - walk around for 30 seconds - massage own neck - close eyes and count to 30 - look out the window and look at the clouds - shake around hands - drink some water, etc. * Mini-breaks: duration about 35 minutes (about every hour) - stay at the work location, breathe deeply a few times - rest head on the desk or on knees - leave the workplace briefly and get some fresh air * Coffee breaks: duration 1520 minutes, leave work location (after about 2 hours work). * Rest break: duration 12.5 hours (after about 3.5 hours work). Many people feel distracted by their own thoughts due to fatigue when dealing with longer tasks. Such mental "pseudo-breaks" are bad for concentration. So-called "mindfulness exercises" can be helpful as short interruptions: * Direct you perception outwards: Our attention is often focused inwardly when we're tired, pursuing all sorts of thoughts that are actually not at all important at the moment. In such cases, it is helpful to direct our perception outwards. For example, I can look at the color and shape of objects in my workplace or the structure of the wall in the room. The important thing is that we only describe (round, square, white, black, edged, etc.) and not evaluate (beautiful, ugly, stingy, narrow, cool, comfortable, cozy, etc.). V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 6 Filter Model of Perception * * We perceive with all 5 senses: we see, hear, smell, touch, and taste. What we perceive depends on our memory and the experiences stored there. Or the other way round: Our earlier experiences determine what we perceive today. * Our capacity of perception is selective. What we perceive is also filtered. The selection of information that we perceive depends on various influences (filters). Among these are mood and feeling, our interests, our alertness and attention, our attitudes and personality, and the current activation level of these filters. Our perception also depends on how important something is to us in a certain situation. Impressions selection / filter Perception (visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, haptic) selection / filter Memory/ Memories V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 7 How do I Recognize the Feelings of Others? * Various facial features betray the feelings of others: for example, how the eyes are opened, the shape of one's eyebrows, nose, or mouth, or the wrinkles around the mouth and eyes and on the nose or forehead. In total, our facial expressions make use of about 17 different facial muscles. neutral: no facial expression pleasure: anger/ rage: •corner of the mouth turned upwards • open mouth • laugh lines under the eyes and with mouth wrinkles • eyebrows drawn together • lips pressed together • frown lines between the eyebrows anxiety / fear: disgust: • wide eyes • strained lower eyelid • slightly open mouth • turned up nose • skewed lips • eyebrows drawn together grief: surprise: • mouth and eye wrinkles pulled down • large eyes • open mouth • wrinkles in forehead V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 8 A gesture often says more than 1000 words! * Gestures and facial expressions, these accentuate our feelings using body language. * With our gestures and facial expressions, we send signals to our environment. They are means of communication. * Our gestures disclose, in a given situation (e.g. we come across a barking dog), how we: - feel (e.g. we're afraid), - what we think (e.g. "The dog wants to bite me!"), - our physical reactions (e.g. difficulty breathing, sweating, rapid heartbeat), - our behavioral reactions (e.g. we freeze or retreat). * A certain gesture basically consists of a facial expression, posture, arm position, hands and fingers. * Posture: Whether we bend forwards (e.g. showing attraction or expression aggression) or shyly pull back (e.g. showing fear, insecurity, or even disgust), or stand or sit very straight (e.g. expressing self-confidence), each posture sends a different signal to others and is also perceived differently by ourselves. * Arms: Whether we stretch out our arms in front of us (e.g. "Stop, you're coming too close!" or "I'm afraid of you"), extend them sideways ("Come into my arms, I like you"), cross them ("I'm not interested!"), place them on our own bodies ("I'm in pain"), put them on our hips ("I'm the boss here"), or let them fall behind our bodies ("I'm not a danger to you, but I am interested in what you're saying") -- these are all examples of different emotional states. * Hands and fingers: These also can be used to make different gestures that other people interpret: Sticking out the thumb upwards ("OK!") or downwards ("not OK"), lifting only the middle finger ("vulgar insult"), the index finger ("note"), the index and middle fingers ("victory!" or "peace"), the thumb, index and middle fingers ("I swear!"), or the index and little fingers ("putting on horns"), making a fist ("threat"), extending an open hand ("help" or "begging"), pressing two flat hands together ("please" or "praying"), extending one hand upwards ("stop!") – these are generally understandable signs which accentuate our own feelings. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 9 Memory The power of memory: When we use our memory, this process can be divided into 3 parts: Memory Encoding Storage Retrieval Learning When we have perceived something we imprint it in our memory (learn). Part of what we quickly imprint is stored. For example, when we have learned something and associate it with other contents in our memory. The rest is lost again, since we don't consider everything important, and everyone's storage capacity is limited. If we remember something or wish to make use of something we have learned, we retrieve the stored memory contents. Types of memory: There are different types of memory. In everyday life, we usually make a distinction between short-term and long-term memory. * Short-term memory is comprised of the part of our memory in which we store information for up to 20 seconds. Its intake capacity is very limited (59 items such as words, numbers, etc.), which is already a decisive factor influencing what we will or will not remember later. By shielding ourselves from outside stimuli while learning (no distraction due to nboise etc.) and by repeating the items to be learned, they can be stored in short-term memory for longer than 30 seconds. * Long-term memory on the other hand contains everything that a person knows. Here, new content is linked and compared with old content and processed so we can retrieve it later. Events and experiences are also stored here, which together lead to the formation of skills: e.g. knowledge of how to drive a car or how to speak Spanish. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 10 Memory Contents In our memory, the most diverse contents are stored which we perceive with all our senses (seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, tasting). We learn in this way what we like to smell or taste, what our favorite color is, what noises we don't like or what surfaces we like to feel. We will now have a closer look at the following memory contents: * Language: Most of the information that we absorb and store is language-based -- things that we have heard or read. Language connects: we can speak with each other, read and listen. Our education is also based on language-based concepts. even mathematics would be impossible without language. Many people find it especially difficult to remember names. * Numbers: A lot of everyday information these days is based on numbers or number series: house numbers, floor numbers in the elevator, calendar days, birthdays, telephone numbers, credit card codes. We are forced to orient ourselves according to numbers when planning and going about our everyday lives. However, most people find it more difficult to remember numbers than words. * Word lists: Who can forget the laborious tasks of language instruction in school, when abstract poems or French vocabulary lists had to be memorized or when our biology teachers tested our knowledge of the strangest lists of specialized terms? We are often forced to store and later to retrieve lists of concepts in everyday life, too. Shopping lists, for example. * Pictures: When we meet someone we know, we recognize that person by their face, and sometimes by their clothes or already by their walk. We thus find that images of people and places are also stored in our memory. * Future events: It might sound like a contradiction, but we also remember future events! In our everyday lives, it can be highly detrimental to forget a coming doctor's appointment, meeting, a partner's birthday, or a first day at work. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 11 Memory Tricks: Inquire, repeat, and write everything down There are various methods to help us remember things better. In principle, the intake capacity of our memory is limited. As a rule, we can retain information in our short-term memory for up to 20 seconds. Beyond 20 seconds, it becomes more difficult (long-term memory) and we tend to forget the information. Important: Every person has a limited capacity for absorbing information. So it is always practical and clever to write the information down! This requires that one understands the information correctly. To ensure this, it helps to repeat the information in or own words and to ask questions if we don't understand something completely. * Keep a memo pad and pen handy next to the telephone at home or at work so that you can immediately write everything down. * Carry a little note pad with you that you can use during important conversations. It is also possible to take notes using mobile devices. * Asking questions: In a (telephone) conversation, ask questions until you have understood the information well and until you have it written on paper. * Repeat the information, e.g. about taking medication at the doctor's office. Immediately write the information down or have someone write it down for you. * For example, repeat your boss's instructions to yourself and write them down. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 12 Memory Tricks: Using the Senses If you cannot write something down immediately, there are different strategies for remembering things better. The most important is that one first tries to concentrate quite consciously on "remembering" ("I want to remember this!"). Use different senses: Repeat information internally or say it out loud: * For example, repeat information given on the telephone (telephone number, address, date, etc.) by saying it internally or out loud. Repeat the information internally a few times, if possible until you have something to write with. * Repeat the name of someone you just met internally, or try to incorporate his or her name continually in the conversation: "I see, Mr. Meier. That's very interesting. What's your opinion, Mr. Meier? Until next time, Mr. Meier.“ * Associate the concept you need to remember with a melody. Make a mental image of the information: * For example, close your eyes when on the telephone and imagine the information (telephone number, address, date, etc.) written on a blackboard. * Make an image of the name of a person you have just met. For example, imagine an acquaintance of yours who has the same name (e.g. Reto Meier with the long beard next door..., or she has the same name as my coworker Meier). * Connect the term or name you have to remember with something concrete and make a mental image: for example, imagine Mr. King as a medieval king, Mrs. Baker as a baker with a white apron, or the city of Turin as a tunnel filled with urine. The stranger the image, the easier the item will be imprinted in your memory. Associate concepts with body parts or familiar objects: * e.g. how many days are in each month of the year can be counted off on our knuckles and the spaces in between if we make a fist: The 1st month (January) on the 1st knuckle has 31 days, the 2nd month between the knuckles has 30, the 3rd has 31 again, etc. The only exception is February, which only has 28 or 29 days. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 13 Tricks for Remembering Several Concepts Sometimes it is necessary to remember several concepts at the same time, for example in the case of lists, which includes probably the most typical everyday example, shopping lists. For instance, if you were not able to write down a shopping list or would like to memorize a list of terms, there is a series of learning strategies that can help you: * Classifying shopping items: since our memories are limited and it is difficult to remember more than 5 to 9 different things, the trick of classifying several similar items on one's shopping list under categories is often helpful. Then we need only remember 3 to 4 categories. For example, we can use the categories of drinks (milk, orange juice, cola), fruits/vegetables (cucumbers, potatoes, apples, bananas), and staple foods (butter, sugar, flour, bread). * Associating objects with places: it is also often helpful to imagine the objects to be acquired at their usual location in one's residence. Imagine you are walking through your apartment in a natural sequence, such as from the bedroom (magazine on the night table) to the bathroom (toothpaste, shower gel), from there through the hall (batteries in the cabinet), into the kitchen (bread, drinks, yogurt), and then into the living room (candles). * Putting concepts into a story: as a rule, we can learn lists of concepts better is we put them into a story we have made up: For example, the shopping list "apples, bananas, tooth paste, milk, sweater, cleaning cloth" can be put into the following story: "My husband acts like an ape sometimes: in one hand he holds a banana, in the other an apple. That he is dressed only in a sweater and has the cleaning cloth on his head betrays the fact that he has once again done no chores." The funnier or stranger the story is, the easier it will be to imprint the concepts in your mind. * Initial letters: from the 1st letter of each term in a list, a word or sentence can be formed: for example, from the ingredients "beef, apples, spinach, eggs, bacon, asparagus, lemons, leeks" we can form the word B-A-S-E-BA-L-L. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 14 Memory Tricks for Numbers Most people find it more difficult to remember numbers than words. Who hasn't ever forgotten a telephone number, one's own credit card number, or the birthday of someone close? There are a number of learning strategies to help remember numbers as well: * Separating lines of numbers into units of 2, 3, or 4: This method is used most often in everyday life when learning and writing down telephone numbers: From the fictitious international Swiss telephone number 0041312548312 we obtain 0041 (Swiss code) 31 (Bern code) 254 (Quartier code) and 83 12 (two individual two-digit numbers). From 13 figures we now have 5 easily remembered numbers. * Put the number list to a melody: This learning strategy is often used in TV commercials. * Number-word association: If you have to memorize longer lists of numbers, a credit card code for example, it helps to translate the individual figures into words, which are more appealing to the imagination. Words which rhyme with the numbers, sound similar, or have personal significance as especially suited: the code 8108341 then becomes "It's great (8) to end (10) a date (8) at my age (34) with one (1) drink.” * Imagining numbers in a mental image: As we already learned in memorizing words, we can also imagine lists of numbers on a chalk board, written on a door, or as a neon sign on a building. * Assigning numbers to a picture: Each number between 0 and 9 is assigned to a picture: e.g. 0=ball or egg; 2=twins or swan; 3=tricycle; 4=table or chair with 4 legs; 5=hand with 5 fingers; 6=dice or cube with 6 sides; 7=dormouse or week with 7 days; 8=hourglass or toy race track; 9=bowling. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 15a Memory Tricks for Appointments or Future Events (Part 1) We are generally forced to plan our daily lives so that we do not miss things like doctor's appointments, meetings, birthdays, our parents' anniversary, etc. Thus, our memory is also needed when planning future events. There are several ways, some of which you may already know, that can help you to remember future events better: Keep a schedule: * Carry your scheduler with you as much as possible. It should not be to large but still have enough space to write down the most important information. * * Electronic aids such as mobile phones also have scheduling options. Check your schedule every day: associate a regular activity with checking your schedule: after waking, drinking morning coffee, eating breakfast, etc. * Make yourself a note as an aid not to remember checking (for example, on the mirror in the bathroom, on the front door). * Write down all appointments: indicate the name, location, telephone number, short notes (for example: "discuss side effects with the doctor"). * Also write down telephone numbers and addresses of all private or professional persons you know (friends, acquaintances, family, doctor, coworkers, etc.). Use a calendar at home: * Choose a calendar of sufficient size to enter appointments on individual days. * Display the calendar in a highly visible location (for example, in the kitchen, next to the front door). * Make special "sessions" for planning with your calendar (weekly planning every Sunday evening, for instance). Check your appointments for the following week. Are they also written in your scheduler? * Enter new appointments, which you already know about, in your calendar. Then your calendar will always be up-to-date. A calendar is also good for writing down telephone numbers you often need or which are generally important. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 15b Memory Tricks for Appointments or Future Events (Part 2) Use a bulletin board for notes: * It is helpful to have a bulletin board at the same location as the calendar. *Make a note as a memory aid and pin it to the bulletin board: for example, * shopping lists, * names of medications, information on doses and use, * things that you want to and have to take care of. * Make up levels of urgency as well: for instance, keep notes of things that have to be done in the next few days up top. Things that can be done in the long-term would then be on the bottom. * Often the refrigerator door is used to hang up notes with magnets instead of bulletin boards. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 16 Perceiving a Situation * Interpreting what we perceive: When we see others communicate and express feeling, gestures and other types of behavior in the process, it is advantageous to be able to recognize as quickly as possible what is going on in the situation. This is especially important when we would like to take part in a conversation. We have to interpret the information we perceive correctly and get tot he heart of the matter as quickly as we can. Our experience with similar situations and our reasoning capacity help us with this. * The whole equals more than the sum of its parts: When we perceive a situation or, for example, look at a photo of a situation, we receive information from various parts of the overall picture. For example, when someone smiles, it makes a difference whether this person is doing so because of a funny thought or because of a gesture made by somebody else. When interpreting a picture, we must thus get an overall impression from different parts, just like putting together a puzzle. Puzzle Picture V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 17 Assumptions are not the same as facts! * Assumptions: What we perceive with our senses is often influenced by our personal experiences and expectations. We often see or hear what we want to see or hear. When we see, for example, two people doing something together, we often allow ourselves very quickly to be led by our assumptions when interpreting their actions. However, this puts us in danger of interpreting a situation incorrectly. * Facts: It is thus advantageous to orient ourselves first by facts. Facts are what is really there, what other people would recognize and describe just like we would. Facts are things like a table, a chair, a car, people, people's clothing. When two people talk to each other, if one of them has wide eyes, an open mouth, or an extended arm or finger -- these too are facts. * Distinguishing between facts and assumptions: In order to recognize or understand what is going on in a situation, it is important to distinguish between facts and one's own assumptions. Example: Two people are shown in the picture below. What is happening between the two people? What are the facts? Where are we making assumptions in our interpretation? What is the man pointing to? V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 18 Empathizing with others When we have to deal with other people, exchange views, or read what another person has written, we are forced to orient ourselves by others. The experience we can draw upon helps us in this. Also, we often have to be able to empathize with others in order to recognize what he or she is thinking or feeling at the moment. This is crucial in basic activities such as watching, reading, and listening: * Watching: When we watch others as they do something (playing a game, for example) we usually want to know what is going on. Otherwise it would quickly get boring. In a football game for example, we ask ourselves why a player in front is running zigzag and not straight towards the opposing goal when he sees that a play wants to pass the ball to him. To understand this, it helps to put ourselves in that player's shoes. Maybe he's thinking that he would run offside if he ran straight towards the opposing goal since he has to orient himself by the opposing players. Or in other words, he has to follow the rules of the game. So it is important to understand the rules when we watch football. School was similar: the better we knew what a certain teacher wanted from us, the fewer problems we had! * Reading: When reading a novel, we automatically have to put ourselves into the plot and empathize with the characters involved in order to follow the story. This is particularly the case when reading comics, since here individual pictures and speech bubbles are arranged one on the other, and sometimes it isn't clear which picture is supposed to follow which. The advantage of a book is that we can read every page, every paragraph more than once. We can also put the book aside and fetch it again later. In addition, repeated practice helps us when we read. We learn to understand a text better and better. * Listening: when someone tells us something or we are listening to others talking to each other, sometimes it's difficult to follow. This is especially because we have to visualize what is being said immediately . Otherwise it will be too late. For example, someone is telling us about his vacation and describes his experiences. We will try to visualize what the person is telling us and what he felt at the time. We will try to empathize with him and put his story in our own words. In doing so, we also pay attention to facial expressions, gestures, and the tone of voice the other is using. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 19 Possible means of assistance to improve our empathy with others * First stick to the facts! We should constantly be certain about whether our assumptions or interpretations can be covered by the facts. Facts can include: - What is said or written (the content of what is said or written) - How something is said (tone of voice, volume of what is said, choice of spoken/written words) - Nonverbal behavior (gestures, facial expressions, typical behavior patterns like eye contact, motions, posture) - Where and when something is said or written (place, persons present) - Applicable rules (according to which a game should be played or we should behave) * How would I act in this situation, what would I think and feel? Relate the other's situation to yourself. * Have I already experienced, seen, or heard this situation? Utilize your own experiences. * * Put what was said in your own words! Make a mental image! When someone tells us something, it can be helpful to visualize it with a mental image or film, in which the other person's words are reproduced. * Practice! The more we try to empathize with others (when reading, for example), the easier it becomes. * * * .... .... .... V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 20 I think, therefore I am Every human being thinks. Our ability to reason is an essential part of our being. When we see, hear, smell or intend to do something, we have thoughts about it. It is difficult not to think, even when we're lying in bed with the blanket pulled over our head. * When we think, we use our experiences and acquired knowledge stored in our memory in order to properly classify and understand new sense perceptions or a sudden idea. In other words: We have to assign and delimit in order to check whether a new perception fits what we are already familiar with and know. * When we think, we mostly form words or sentences, and sometimes we also imagine something in the process. Reasoning, in a sense, is the language of our minds. Reasoning requires a high level of flexibility: For example, when we are talking to someone, we are forced to find the right words promptly. This process is often affected by our mood and feelings, sometimes hindered. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 21 Reasoning, a Matter of the Brain Words and concepts are stored in our memory in a kind of network of nodes. Concepts that tend to belong together are connected directly, while dissimilar concepts are further away and tend to be independent of each other. For instance, the word "banana" is more closely associated with "apple", "ape", and "yellow" than with "plate", "kitchen", and "white" (see figure below). chimpanzee peel yellow ape kitchen banana drink eat dishes fruit plate glass cup white * There are people who sometimes find it difficult to find the right "nodes" (words/concepts that is) in these patterns. Many of us have experienced that sometimes we can't find the right words and, as a result, we can't relate things to others very intelligibly. This then makes it hard for others to understand us. * There are others who find concepts and words too quickly. Concepts, that don't actually belong together are activated quickly in their memories. Such people tend to have difficulty explaining things to others because they are jumping from one thing to the next. Other people find this difficult to understand. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 22 What influences are our reasoning and problemsolving exposed to? In everyday life, we sometimes find that reasoning is an easy matter in a certain situation -- we recognize the problem quickly and find a solution right away. But in other situations, we have to make a huge effort and feel blocked. Why is that the case? Our ability to use our powers of reasoning and problem-solving often depends on various influences related to ourselves or the situation and the environment. Examples: * Emotional strain triggered by the situation: the more we are involved in a problem and the more important its solution is, the more difficult it is to solve the problem (closeness/distance to the problem). * Our mood affects our powers of reasoning and problem-solving: If we are too nervous or tense, we often experience more difficulty and can't concentrate as well. The same is true when we have no interest or inclination, since then our attention and alertness tend to be low. As a rule, we reason best when we are slightly, but not overly tense and excited. * Major stress reduces our ability to reason and to plan solutions. Stress can come from ourselves ("I'll be very nervous all day today". "I'm putting myself under pressure") or from our environment (sensory overload, time pressure from the boss, etc.). * Our ability to reason and solve problems in a certain situation also depends on how well we can concentrate at the moment, how quickly we are able to process the necessary information and how well we can use our memory in the process. * Another possible influence: ...... * Another possible influence: ...... V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 23 Difficulties Reaching a Goal In everyday life, we are often occupied with reaching goals and acting in accordance with goals: be it in leisure time, say, going into town to buy something or cooking something at home, or at work, when we have to carry out an order from our boss for example, or even in relationships, when we want to make a date with a co-worker, for example. The following difficulties can arise when we want to reach a goal: * * * * * It is not completely clear to me what I actually want or need to achieve. I have to ideas or solutions about how to reach the goal. I have some solutions or ideas, but I don't know which would be best. I see "a mountain" ahead and can't recognize any smaller steps towards the ultimate goal. I've gotten going and am moving in the direction of my goal, but the solution isn't working. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 24 Steps for Reaching a Goal In order to reach a goal or fulfill a wish or task, it helps to structure the way to the goal well, that is, to plan. The following planning steps have proved useful: 1. Define the goal or want clearly * "I know what I want to/should/must do" 2. Brainstorm as many ideas and possibilities of how to reach the goal and fulfill the want as possible * "Many possibilities are available to me" 3. Think about possible solutions and assess the consequences * "I know how useful each possibility is" 4. Choose one path to the goal * "I know how I'm going to do it" 5. Planning implementation and dividing into intermediate goals * "I know what I'm going to do when" 6. Reviewing and assessing the action * "I know whether I will continue this way or have to find another solution" V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 25 From a Complicated Action to Small Action Steps In everyday life, we are sometimes forced to plan and implement complex actions. When we are doing very well and everything is easier for us, this works automatically without the need for much reflection. Yet there are also situations in which everything is more difficult for us. Then we feel unsure while we are planning and we begin to doubt whether we can do what we planned, even if we would otherwise be able to do it without a problem. In other words, we feel over-challenged. In such situations, it can be helpful to divide the complicated task into small partial tasks. Each partial task is then less threatening and straining. The only important thing is that we plan the individual subtasks well and put them back into the right sequence. Example: I have to get from A (start) to (E) goal via B, C, and D (3 intermediate points). A B C Start D E Goal The following questions are helpful in this situation: * "What do I have to do first?" I have to go to the start (A), otherwise I can't begin! * "What is the final goal and how do I get there?" I want to get to E (goal). To do that, I have to get past A, B, and C (intermediate points)! * "What kind of prerequisites does an intermediate step have that I have to take care of first before I can take that step? In what order do I have to put the intermediate steps?" In order to get to C, I must first have been to A and B, etc. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 26 How can I better find the right words? Sometimes we would like to say something directly to someone or take part in a conversation but we have trouble finding the right words. The same time also happens sometimes when we are writing a letter or want to communicate something to someone. We can't find the words! The following strategies have proved helpful for finding the right words better and sometimes faster: * Practice makes perfect: It is unpleasant when we notice that we're having trouble expressing ourselves. We often tend in such cases to stay silent or withdraw ourselves so we don't have to say anything. Perfectly in line with the motto: if you don't say or write anything, you can't do anything wrong! But we often achieve the exact opposite with such a head-in-thesand tactic. The more we withdraw ourselves and say nothing, the more we isolate ourselves and the more difficult it will be for us to say something in future when we want to. For this reason, it is important that we stay on the ball and practice. Practice gives us confidence and self-assurance. * Clarify the goal: It often also helps to consider what we actually want to say or write or what others expect us to say or write. However, we must then distinguish between what we merely assume others expect from us and for what there is actual factual evidence. There is often a big difference between our spontaneous assumptions and what is actually happening. * Group ideas: It is also often difficult for us to organize the various details and ideas that we want to relate so that our conversation partner understands what we want to communicate. It helps to group details into categories (e.g. pasta, bread,, sausage, and vegetables are all food, jogging, playing football, and swimming are all recreational and sport activities). Then we can organize our thoughts better and orient ourselves in the conversation. * Check whether something fits the topic: If we try to think in categories and group our ideas, it is easier for us to check whether something fits a conversation topic or not. For example, if people are discussing different foods like meat, pasta, etc., remarks about a football match don't tend to fit. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 27 Social Rules and Roles Whenever we have to deal with other people in everyday life, our actions are also regulated by social rules. We know without thinking about it what we should or are allowed to do and what is not appropriate. We all act automatically in accordance with these rules. In other words, we are familiar with the commandments and prohibitions that regulate our social coexistence. Such rules include not only universally known legal rules like ”you shall not steal" or "You must observe traffic laws" but also less easily recognizable rules like how to behave in a restaurant, a supermarket, or a conversation. Social rules determine our coexistence with other people! The social rules which we orient ourselves by can vary, however. The rules change depending on the social role in which we find ourselves. For example, a 10-year-old schoolboy does not have as many liberties as a teacher or an adult. If the teacher is speaking in front of the class, it is sometimes not a good idea to interrupt him or her as a pupil. On the other hand, the teacher occasionally disciplines a pupil for taking too loudly. Similar differences can be seen at the workplace: the boss has a completely different role than one of the many subordinate employees. But neither a schoolboy nor an employee needs to think very much about how to play out their role properly. They do so automatically. What both cases – the pupil/teacher and employee/boss relationships – have in common is that the pupil and the employee feel "small" in their roles, while the teacher or boss tend to feel "big". In everyday life however, we also experience opposite situations: if someone asks us for information or a favor, then the person asking is, in a smaller sense, "small" and we are "big" since the person wants something from us which we can choose to give or not. In addition, we also interact with coworkers or fellow students, neighbors, or family members, without one person expecting something from the other person. Then we are on the same level with our conversation partner; both are equal and occupy the exact same roles. Social rules depend on the social roles that we are acting out at the given moment! V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 28 How do I recognize that my behavior doesn't conform to rules? Social rules determine our coexistence in the world without us having to think about them much. It simply happens, without exertion, even if we sometimes interpret the rules differently. Violations of such rules can lead to unpleasant experiences of stress. In other words, behavior that does not conform to rules leads to strain, which we would rather avoid. Such strain can be avoided or at least reduced by early recognizing the threat of rule violation early. The following points can help us: Pay attention to your own feelings: As a rule, we sense when we are not sure whether we are behaving "correctly". We also notice when we have the feeling that we have behaved "wrongly". Then lose selfconfidence, become sad, or get anxious. Or we become furious because we think we've screwed up yet again. These feelings are often accompanied by physical sensations such as rapid heartbeat, sweating, or feeling unwell. Pay attention to other people's reactions: We can often also tell from the reactions of others whether our own behavior does not fit the demands of the situation. We can orient ourselves by other people's facial expressions or gestures or by how they speak. Is someone shaking their head, shrugging their shoulders, or have they stopped talking? But don't forget: everyone violates interpersonal rules once in a while! And sometimes people purposely break these rules for fun. Identify the rules: Also, it is sometimes helpful to consider what we and others expect in the situation at hand. What rules are we playing by here? Yet often such thoughts are only possible if we aren't overly excited and strained yet. Then we must first calm down, maybe remove ourselves from the situation briefly and then return to it. Other strategies: ... V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 29a Being able to distance ourselves easier said than done Unfortunately, sometimes people with mental problems are ostracized (stigmatization). For many, this leads to a fear of how others will react when they find out about their mental difficulties. Let's say that Peter has been hospitalized for three weeks in a mental hospital. When he returns home, his neighbor asks him where he was the whole time. What can Peter do in this situation? What should he say? There is no instruction manual for how a person like Peter should handle such a situation. Each individual has to decide for himself or herself. It isn't easy for everyone to come up with an answer to such a question immediately. But it can be helpful to reflect for a moment what possibilities are available. Should we be open with our own problems, or would it be better to distance ourselves? And is it true for all persons who talk to us? The following strategies are possible for Peter: Call a spade a spade: Peter tells his neighbor where he was that last three weeks, what the reason was, and how he is doing better as a result. The last point is especially important and is often forgotten: "Now I can cope with my problems better!” Run away: Peter doesn't say a word and runs away. In line with the motto, "out of sight, out of mind", this action leads to short-term tension release. I'm not talking about it! Peter says that he can't or doesn't want to talk about it (at the moment). White lie: Peter tells his neighbor he was on holiday in the mountains for three weeks, where he could relax wonderfully. Partial report: Peter says he was in a hospital for a while, but he doesn't go into any details. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 29b Being able to distance ourselves easier said than done (Part 2) Other strategies: Half-truth: Peters says that he was in the hospital, where people helped him. But as a reason for going to the hospital he mentions acute stomach pains, suggesting he was suffering from physical ailments. Thus, in contrast to a "partial report", this strategy is a mixture of the two strategies of "calling a spade a spade" and the "white lie". The politician's strategy: But it is also possible to say a lot without disclosing any information – just as politicians often do. Yet to do this we need to take charge of the conversation. Whoever leads the discussion determines the topics! Peter thus answers the question of "Where were you the last three weeks?" with: "Hey, I'm doing great. I just picked up a new hobby. Painting. Have you ever tried to paint? What do you think of that?" Peter is thus taking charge and changes the topic. He knows that curious neighbors will inquire about what they actually want to know two or three more times at most before they finally let the matter rest. With whom do I use each strategy? As a rule, we give varying amounts of information about ourselves to our partner, particular family members, friends, neighbors, co-workers, our boss, or unfamiliar people. We must thus assess what we want to tell to who, who we want to distance ourselves from more and who less. This assessment ultimately also determines which strategy we use with whom. Practice makes perfect: It is also true in this case: the more we apply a distancing strategy, the greater our self-confidence we have to do so! With more self-confidence, fear of the mental strain of experiencing situations like Peter's is also reduced. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 30 Working Actively with Memory We need our memory not only to store and later recall names, telephone numbers, or the contents of a book. We are also working actively with our memory in most situation! In the process, we utilize most of the reasoning functions that we have already talked about: We are attentive and concentrate on the requirements of the situation. We often have to think and act quickly, and we sometimes must also solve a problem and reach a goal. We then store the relevant information in our memory and attempt to link it with our experiences and our knowledge. To do this, we need something like a control center that coordinates the demands of a situation with the aforementioned reasoning functions (cognitions) so that we behave appropriately to the situation. We work actively and consciously with our memory! This is all the more difficult the more challenging and complex the situation is in which we are. For example: When we have to carry out several tasks at the same time: for example, phoning while riding a bike or cooking, or doing a calculation at school while our schoolmate is telling us about her new boyfriend. When we are distracted by internal stimuli: for example, when a situation is too emotionally straining for us ("I'm afraid to talk to my boss.") When we are distracted by external stimuli: for example, when we are looking for someone in a crowded restaurant and are trying not to get distracted by noise or other people. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 31 Costs and Benefits of Behavior Change Human beings are creatures of habit. A large part of our behavior is always the same. That is, we often follow individual action rituals in our everyday lives. Always doing something the same way brings us benefits (advantages) on the one hand, but can also cost us something (disadvantages that we accept). Potential benefits and costs are shown in the figure below: Benefits of the accustomed Costs of the accustomed - security - orientation - having control - being inflexible towards the new - deviation from norms - less effective Scale of habit If new behavior types are used in order to better reach a goal or to better deal with strain, then the cost/benefit scale is shifted: Benefits of the new Benefits of the new - flexible towards the new - conforming to the norm - effective - lack of security - less orientation - less control Scale of the new A mixture of new and accustomed behaviors is often advantageous: being able to trust in what has been tried and tested and still being flexible enough to try something new when it is necessary. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 32 Strategies for Avoiding Distraction when Performing Actions Structure activities: An external structure can help us switch better between different actions. You can imagine, for instance, that it is easier to concentrate on a task when someone always tells you what is to be done next. In everyday life, we can try to structure our actions as well as possible. We are already familiar with possible strategies for doing this from earlier sessions. The following examples have proved effective: Dividing the task into smaller steps (e.g. when cooking). Listing individual steps and checking them off when you have finished them (write on a slip of paper!). Making a daily schedule with particular activities. Ask orientation questions: - What have I already done? - What have I just done now? - What's next? Preventing interruptions - Hang a "Do Not Disturb" sign on the door - Silence the telephone/answering machine etc. Choose a more helpful environment: When you go shopping or out to eat, you can, for example, choose where you are going. In such cases, a more helpful environment would be a quiet restaurant, a smaller shop, or a less frequented time of day with fewer customers in a large shopping center. Other strategies: .... .... Important: Find a path between total avoidance of distraction due to too much stress (no longer leaving home, not shopping anymore) and overstimulation due to sensory overload! Apply your strategies again and again! V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 33 Focusing Concentration When we are distracted by internal stimuli (our own thoughts, feelings, nervousness, expectations, etc.) or by external stimuli (other people, noise, bright light, etc.), it is generally difficult to concentrate on a certain thing, to focus our attention on it, and to block out everything else. The following strategies have proved helpful for focusing our own concentration: Say to yourself that only the task at hand is important right now and nothing else: e.g. if I have to shoot down a box pyramid with 3 balls at an annual fair, it's helpful to tell myself that at the moment only the boxes (target), the ball in my hand (throwing object), and me (the thrower) are important, and I "forget" everything else around me. Encourage yourself to concentrate on something: e.g. if I am looking for something at the supermarket and I don't find it right away, I tell myself that I will find what I'm looking for now, that I will be successful because I am now going to concentrate on it and, if need be, can get help from a shop assistant. Optimize physical tension: e.g. before physically demanding activities, briefly tense and relax your arm and back muscles, breathe deeply, or strike your chest with your fists like top athletes do before a competition. Narrow your field of vision: e.g. if I want to knock down the box pyramid at the annual fair, I look only at the boxes (target) and not to the left, the right, up, or down. Make use of earlier experiences: e.g. if I want to find a friend I am supposed to meet in a large group of people, it helps to consider what I did previously in such situations or how exactly my friend looks, how tall he is, or what kind of jacket he's probably wearing. Other strategies: V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 34 Distractibility During Conversation Distractibility also plays a great role in conversations with others. Being able to stay attentive during a conversation is needed to understand others and to be able to remember what was said later. There are various ways to reduce distraction during a conversation and to focus our concentration on the content of the conversation: Remove sources of distraction: Whenever we have a conversation, we should be sure not to be disturbed by anything. At home for instance, I can turn off the TV when I'm on the phone. Or if I live with others, I can go into an empty room so as not to be disturbed. Always stop the activity that you are doing at the moment! It is very difficult to concentrate on several things at once. For example, I can turn off the stove top when I get a phone call. Or I ask the caller to call back later. Briefly assert yourself: If many people at sitting at a table talking chaotically and I would like to say something to the host, it helps to interrupt the other people ("Please be a bit quiet for a moment. I'd like to say something to our host!"). If this is impossible, get up and change the side of the table you are sitting at. Make eye contact: In conversations it is of great importance for attention and memory to look at the conversation partner while listening. Sometimes we feel slightly uncomfortable looking a person directly in the eyes. But it gets easier with practice! Repeat in your own words: Interrupt the conversation now and then and repeat what you have understood in your own words. This is very helpful for making sure that you have heard and understood something correctly. It also lets the other person know that you are listening attentively. Ask questions: You can also ask questions now and then about what has been said. You can also ask the person you are talking to whether he can speak a bit more slowly or loudly or repeat something important. Other strategies: .... V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 35 Is it my fault or the fault of others? Internal vs. external causes When something happens or we experience something, we generally try to understand why it happened. We look for explanations. In the process, sometimes we automatically, without thinking about it much, ascribe a cause to an event: for example, we can't find a bag full of important items in the morning, and we suspect that our roommate might have put it somewhere, or we place the blame on ourselves for not remembering where we left the bag the evening before. These two possible ways to ascribe cause can thus be called: Internal causal attribution, directed at oneself: The cause is sought in ourselves ("I'm responsible for this myself!"). This can concern both positive events ("I'm good. That's why it worked out!") and negative events ("It's me who's to blame!"). External causal attribution, directed at other people or the situation: The cause is sought in other people or things ("Other people are responsible for this situation!"). Again, this can be an assessment of positive events ("It worked out well thanks to that person!") or negative events ("That person is to blame. It's not my fault!"). In the example given above of a missing bag, the event remains the same whether we ascribe an internal or external cause to it: We can't find our bag and have to look for it! But the conclusions that we can draw from it are different: If we make our roommate responsible, we might suspect him of a bad intention or at least of lacking tact, since he meddled in our private matters. On the other hand, if we make ourselves responsible, we might conclude that we were once again too distracted, feel less secure of ourselves, and complain that we have a bad memory. The consequences also differ depending on whether our causal attribution is internal or external: if we give ourselves the blame for not finding the bag, we will be better organized in future, always place the bag in the same spot in the evening, and try to concentrate better. On the other hand, if we blame someone else, we'll tell him off at the next opportunity and tell him he should keep his hands off our things. Or we'll become distrustful and suspicious out of fear that he could do us harm again. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 36 What can influence me in ascribing causes? When we want to understand and find causes for what is happening right now, there are various ways in which we are influenced in causal attribution: in addition to the distinction we already made between ascribing the cause of an event to ourselves or to others, the following factors are also possible: The cause can be experienced as stable or variable: The cause is assumed to be stable and always the same. That is to say, we expect that in future the same event will be brought about by the same causes (e.g. "The food tastes bad because I can't cook. I'm sure that it won't be any better in the future!"). The cause of an event is perceived as variable, different from situation to situation. The cause for something is ascribed to chance (e.g. "It was pure chance and luck that I got a goal in the last match. It might be completely different in the next game!"). The cause can be experienced as controllable or uncontrollable: The cause is experienced as controllable when we have the feeling that we could do something ourselves to bring about a different outcome (e.g. "After losing the game, I plan on training more so that we might win the next game."). The cause of an event is experienced as uncontrollable when we judge it to be dependent on others or external circumstances (e.g. "The grade I got on the test depended completely on the teacher and the exam questions"). The cause is related to stress and straining emotions: Stress and emotional strain caused by a situation can affect the way was attribute causes of an event (e.g. "When I'm under stress, I see things differently than when I'm relaxed."). Also, the way we explain an even can trigger stress and emotional strain (e.g. "When I interpret someone's stare as hostile, this can make be feel anxiety."). Other influential factors: V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 37 Vulnerability and Stress We all experience stress in our everyday lives, many more intensely and more frequently than others. Why is this the case? The model below provides an explanation: Vulnerability • inherited • problems during pregnancy/ childhood • metabolism (neurotransmitters) • information processing • ... Stress (emotional strain) Early warning signs Symptoms Vulnerability: The greater our vulnerability, the less stress we can tolerate. If a person has low vulnerability on the other hand, that person is not easily perturbed. There are various factors that determine one´s level of vulnerability. Inheritance, difficulties during pregnancy or in childhood, metabolism by means of neurotransmitters in the brain, and problems with information processing are only a few of many such influential factors. Summing up, we can say that the vulnerability of a person is conditioned by different factors that cannot be influenced by the person himself or herself. Stress: Stress can be generated both internally (by ourselves; our own thoughts, feelings, assumptions, expectations, insecurities) and externally (sensory overload, stressful situations, time pressure). A person's stress tolerance depends on their level of vulnerability, Stress and associated burdening feelings can no longer or barely be coped with beyond a certain point ("I couldn't stand my anxiety any more!"). We are then in danger of developing the first signs of unpleasant sensations ("early warning signs") (e.g. minor perception distortions, thought circles, as well as simple discomfort, excessive fatigue, sleeping problems, etc.). In the worst cases, this can lead to an outbreak of considerable symptoms of illness, which should we should try to avoid. V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 38 How can I better control my own feelings? Our emotions affect our behavior. We strive for positive emotions and prefer to avoid negative emotions. Our emotions activate certain learned or automatic actions (for example, the feeling of fear urges us to run away). Difficulties can arise when our own feelings are too intense, last too long, or don't fit the situation. The ability to control our own feelings is called emotion regulation. The objective is to reduce our negative emotional states (e.g. aggravation) and to create or maintain positive emotional states (e.g. happiness). Model of emotion regulation: Change of situation Situation Choice of situation Attention processes Change of attention Assessment processes Emotional reaction Change of assessment processes Change of emotional reaction V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 39 Strategies for examining our own spontaneous causal attribution When someone says or does something or when something happens, we then try to explain it spontaneously. In other words, we ascribe a cause to the event in order to orient ourselves. When we aren't doing well, are under stress, or have had negative experiences in similar situations before, we often tend to relate the causes of an event to ourselves, to assess the causes as negative or threatening for us, even when that's not the case. The consequence of such misunderstandings is that we feel even worse and our sense of strain rises unnecessarily. There are various ways to check our own spontaneous assumptions and causal attributions: Check spontaneous assumptions against the facts: People have preconceived opinions. This is important for getting though everyday life without too much exertion. These assumptions need not necessarily agree with the facts of a situation. It is thus a good idea to ask ourselves which facts support my spontaneous assumptions and which don't. Compare your own assumptions with the reality of the situation! Take an alternative explanation into consideration: When we have questioned our spontaneous assumptions, we have to consider a new, alternative explanation for the event. It is also possible to think: "If the first explanation was wrong, then I don't know what happened," But saying "I don't know" is usually highly unsatisfying! The following considerations can help to find an alternative explanation: Do I have something to do with it? We often relate everything that happens to ourselves and feel responsible for everything. There is always the possibility that the event was caused by others or the situation itself (e.g. "There's no air in my bicycle tire. Explanations: the neighbor sabotaged my bike to annoy me, or I drove over a nail, or the tube is so old that the air simply leaked out"). Chance? We often forget to take chance into account. Yet ascribing an event to chance is often more relieving than ascribing an intention to other people (e.g. "I just ran into the blond woman in town by chance" or "The blond woman is following me. That's why I just saw her again"). How can I behave differently? Often, a spontaneous assumption results in an associated action. For example, we look away when someone looks at us and start to interpret the other person's supposed devotion to us. It would be helpful in such cases to get more information first before we permit ourselves a judgment ("The other person's gaze was not directed at me, he's expressing sympathy, or the other person is annoyed"). V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 40 Mountain Hike Our journey through life is like a hike in the mountains. Whether we reach our goal and return happily depends on several conditions. Mountain Hike Life Physical Constitution Vulnerability physique, physical shape Rucksack Strain/Stress useful items: map, food, umbrella, sunscreen useful things: daily structure, medications useless burdens: stones, wine bottles, etc. preventable stress: pondering, too much information, alcohol Other Hikers Social Support Behavior Coping behavior walking more slowly, breaks, asking for help Concentrating on what's essential, not pondering too much Symptoms V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 41 Coping with Stress Yourself If we are in a stressful situation in which we have negative thoughts and feelings followed by burdensome physical and behavioral reactions, there are various ways to cope with this. In addition to taking anxiety-preventing, calming medications, there are also other stress-reducing methods available to us: Breathe deeply: Grandmothers often tell their grandchildren, when they are under stress, that they should breathe deeply. This old saying works! Repeated deep breathing leads to short-term physical relaxation. Say "STOP" to your own thoughts: If anxiety-ridden or self-deprecatory thoughts are running through our head in a stressful situation, it would be useful to stop them. This is possible! Say "STOP" to your thoughts. It is also possible merely to think "STOP" when it is not a good idea to shout "STOP" out loud, in a bus for instance, when our stress level is too high surrounded by all the other passengers. The most essential thing about stopping our thoughts is to convince ourselves. Reinforce your "STOP"-thinking with muscular tension or make a fist! Say positive thoughts to yourself: It is also often helpful to talk to yourself in a stressful situation. It calms us down! Say neutral or positive words like "I can do it!", "It's almost over!", If I need it, I'll get help", "I'm good, I can do this!" Avoid negative assessments (e.g. "I'll never make it! I can't stand it anymore! I want to go back home!"). It's better always to say the same phrases to yourself and to practice them beforehand. Focus your attention on something that is not stressful: It also helps to distract yourself and to focus your attention intentionally on something that isn't stressful: e.g. look out the window and describe the surroundings, or describe a single object (e.g. a plastic bottle or a lamp) by its features. The description should be very thorough and include many details (e.g. hues, reflections fo light, foreground/background, etc.). The descriptions should never be evaluative ("I like that – or not"). IMPORTANT: Practice these strategies several times. Start by practicing in non-stressful situations! You should be able to implement these strategies automatically when you need them! V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Information sheet 42 How can I better control my own feelings? Choice of situation: Look for or avoid situations that we know trigger certain emotions in us. • Examples: plan positive activities, exchange view with people, briefly leave the stressful situation. Change of situation: The features of a situation can be changed, thus changing our emotional reaction. • Examples: seek support in a difficult situation, plan short steps, rehearse difficult situations. Change of attention: Techniques for focusing our attention can help us perceive a situation differently and react to it differently. • Examples: distract yourself by listening to music or conversation, concentrate our attention on positive aspects of the situation or on particular details. Change of assessment processes: Re-assess the situation and your own resources. • Examples: Can I also view the situation as a challenge and not only as a threat? Maybe I can master this situation after all? Change of emotional reaction: There are various techniques for influencing our own emotions directly. • Examples: Recall situations in which you felt happy and which you handled successfully; perform relaxation exercises (slow, deep breathing, making fists, stretching); behave opposite to how you feel (e.g. laugh when you're angry); express your emotions (e.g. punch a sandbag when you're angry, run); recognize your "warning signals". V. Roder, D. Müller: INT - Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy for Schizophrenia Patients. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013