The Politics of EU Civilian Interventions and the Strategic Deficit of CSDP

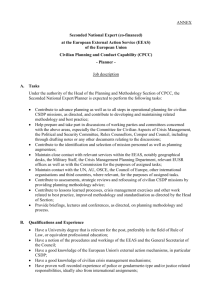

advertisement