538 Elisabeth Dunne et al. 1

advertisement

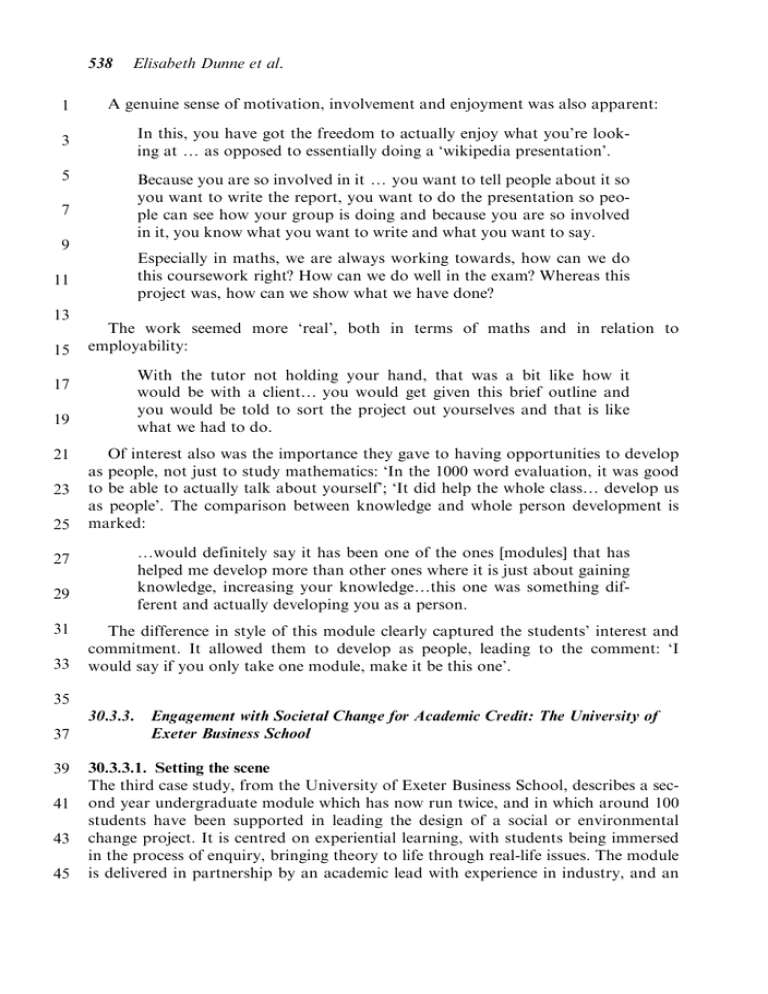

538 Elisabeth Dunne et al. 1 A genuine sense of motivation, involvement and enjoyment was also apparent: 3 In this, you have got the freedom to actually enjoy what you’re looking at … as opposed to essentially doing a ‘wikipedia presentation’. 5 Because you are so involved in it … you want to tell people about it so you want to write the report, you want to do the presentation so people can see how your group is doing and because you are so involved in it, you know what you want to write and what you want to say. 7 9 11 Especially in maths, we are always working towards, how can we do this coursework right? How can we do well in the exam? Whereas this project was, how can we show what we have done? 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 The work seemed more ‘real’, both in terms of maths and in relation to employability: With the tutor not holding your hand, that was a bit like how it would be with a client… you would get given this brief outline and you would be told to sort the project out yourselves and that is like what we had to do. Of interest also was the importance they gave to having opportunities to develop as people, not just to study mathematics: ‘In the 1000 word evaluation, it was good to be able to actually talk about yourself’; ‘It did help the whole class… develop us as people’. The comparison between knowledge and whole person development is marked: …would definitely say it has been one of the ones [modules] that has helped me develop more than other ones where it is just about gaining knowledge, increasing your knowledge…this one was something different and actually developing you as a person. The difference in style of this module clearly captured the students’ interest and commitment. It allowed them to develop as people, leading to the comment: ‘I would say if you only take one module, make it be this one’. 35 37 39 41 43 45 30.3.3. Engagement with Societal Change for Academic Credit: The University of Exeter Business School 30.3.3.1. Setting the scene The third case study, from the University of Exeter Business School, describes a second year undergraduate module which has now run twice, and in which around 100 students have been supported in leading the design of a social or environmental change project. It is centred on experiential learning, with students being immersed in the process of enquiry, bringing theory to life through real-life issues. The module is delivered in partnership by an academic lead with experience in industry, and an Students Engaging with Change 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 539 industry partner with experience in active citizenship and community engagement. The industry expert acts as lead tutor and works with students in the active learning and outreach stages of the module to develop their collective leadership capabilities and to locate enterprises in the community. This allows students to tap in to a ready-made network of community-based leaders and project groups, and introductions by this tutor ensure a positive reception to student requests. The tutor’s skills of working in ‘real life’ community projects are transferred to the student groupings, ensuring that collaboration is encouraged and challenges resolved quickly to move groups towards action. Rather than avoiding the inevitable issues of group-work in large cohorts, students engage with the idea that multiple perspectives are an essential part of working with others to lead change. As emphasized by the Johnson’s several decades of research in the United States (see Johnson & Johnson, 2003), group-work is not an easy option, but it can be highly effective. Culturally heterogeneous groups, as in this module, tend to provide benefits over homogeneous groups, including greater numbers of ideas, improved creativity and flexibility (Kirchmeyer, 1993), provided students have the skills and time to manage the group process (Watson, Kumar, & Michaelsen, 1993). Students learn that if they want to move through society, shaping and influencing, then they must take the time to listen and to understand the perspective of others. That world view is an important part of effective communication; drawing upon one of Covey’s effective habits, they are told ‘seek first to understand and then to be understood’ (Covey, 1989). From week 1, they are asked to ‘switch on their curiosity’ and to start noticing and asking questions about the things they see and hear around them, sharing opinions, ideas and questions. This process supports the group to have a sense of agency, and to identify the change that they would like to see, justify the need for that change and move forward to research and design the project plan. Any difficulties that the students face are highlighted as learning opportunities, supporting them to engage with an unfamiliar and sometimes threatening learning environment. The fear centres inevitably on attainment and uncertainty about assignments and how to do well on the module; many were only used to content which they learnt in order to repeat back. 30.3.3.2. What do students do? Part 1 requires students to engage in active learning, where students are placed in random enquiry groups of six and through a series of exercises begin to form a united group, getting to know each other and establishing the group rules for effective team work. The first three weeks focus on the group learning process, individual differences and multiple perspectives. The in-class exercises are designed to unite the students, aligning personal values and creating a cohesive in-group identity (Haslam, 2004). It is by spending time carefully creating this identity that commitment to the process and the module as a whole is developed. The support invested at the start of the module is essential and seeks to strengthen group identity and underpin the creative process. By the end of this phase, students have begun to shape the social or environmental change projects that they want to pursue. They have an understanding of group values and can see how leadership works as 540 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 Elisabeth Dunne et al. collective experiences. Students are also reminded of the higher order thinking skills required at this stage of their degree programme and how, in developing academic ability, they are also developing skills which transfer to other aspects of their lives. Engagement with the academic literature surrounding leadership and leading change is essential, but students are invited to move beyond theory and consider how ideas and concepts can highlight ways to shape and improve practice. For Part 2, they engage in enquiry, practising their questioning techniques and being coached in the use of enquiry to open up their thinking and challenge their assumptions. They spend time thinking about their change proposal; now is the time to shape their ideas, to use their exposure to others from the wider community to ask questions and to test their project plans. Over two weeks, external practitioners come in to the class; leaders of community projects share their stories and make themselves available for questions. Throughout the enquiry stage, students identify external projects or organisations that interest them. As the students work together to agree upon and then design their change project, they are required to justify the need for their change. This requires engagement with empirical evidence. For some, this will be the first time they have spent time researching a contemporary issue and getting to grips with the validity and reliability issues of data. Students are expected to undertake an external visit to a local charitable or social enterprise to conduct their research. This is often a turning point in their understanding of what it takes to lead change. Through interviewing those that lead change, managers and community workers, students come to appreciate the challenges faced: for example limited or reduced funding, staff turnover, motivating volunteers, preserving the dignity of those in receipt of aid or the need for resilience in pursuit of a strong belief. These challenges may be covered in much of the literature, but the literature does not engage the students in the same way as the impact of their own research. In Part 3, they draw the experience together by engaging in reflection, both as a group when compiling their group project and as an individual when writing their reflective essay. The final student presentations showcase what they have designed, how they have worked together and what change they feel is needed and why. They are asked to share with the audience their values as a group and the leadership approach which they feel best reflects them, to celebrate their unique identity as change agents. This group process comes to an end with the submission of the project assignment, after which they work individually on a reflective essay (‘What does it take to lead change?’), critically reflect on the whole process, use the literature to reflect upon their own experience and use their experience to reflect upon the literature (Brookfield, 1998). 39 41 30.3.3.3. What do students gain? The students’ reflective essays highlight that, for many, there was an uneasy start, especially for some of the international students: 43 45 This module is different. It involves using your knowledge and what you learned during module into practices and it inevitably requires Students Engaging with Change 1 3 5 7 9 11 541 teamwork, which I do not want to be involved in. When I got what the module is completely about, I immediately decided to change module after the induction. But during the induction, being told the purpose of the course, how it will affect your skill and your life, I was inspired by the passion of the founder of the course who wants to make society, the world better. Students later highlight many gains, especially in relation to the processes of working together and what learning really means. There is a sense of ‘journey’: I realised it took more than what meets the eye at first glance. Working with different people from all around the world, each possessing different cultures and an array of ideologies was no mean feat. 13 15 17 19 Made me understand that I shouldn’t just assume, but I should wonder and challenge. I realised how little I knew — the quest to understand what it actually took to lead change successfully opened up with anticipation and eagerness. The developing sense of empowerment is widespread, influencing their futures: 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 This has enabled me to step outside the box and engage in active learning; I didn’t stop when the lecture finished — I was only just getting started. We learn best when in a relationship with others who share a common practice. I therefore hope to increasingly become part of, and create, ‘communities of practice’ where skills and knowledge can be exchanged between people (Wheatley, 2001, p. 6). Enquiry has allowed me to be actively involved in a project, rather than people involved in a linear learning process and having a wrong or right answer which you can investigate no further. Therefore I have become inspired in creating a change initiative. I decided to take challenges and have a sense of curiosity to learn techniques to change my life, my society. Many comments, similarly to the mathematics students, focus on their selfawareness and identity, as a person, a learner and a change agent: Reflecting back on those experiences and feedbacks has helped me understand myself better. …has changed my thinking from now and forever. …has taught me many lessons that help to build a better me. I have become a change agent. AU:3