CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ‘I Don’t Like Your Face!’

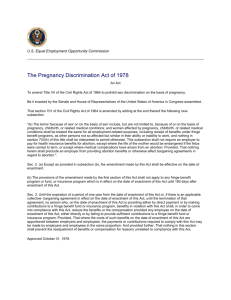

advertisement