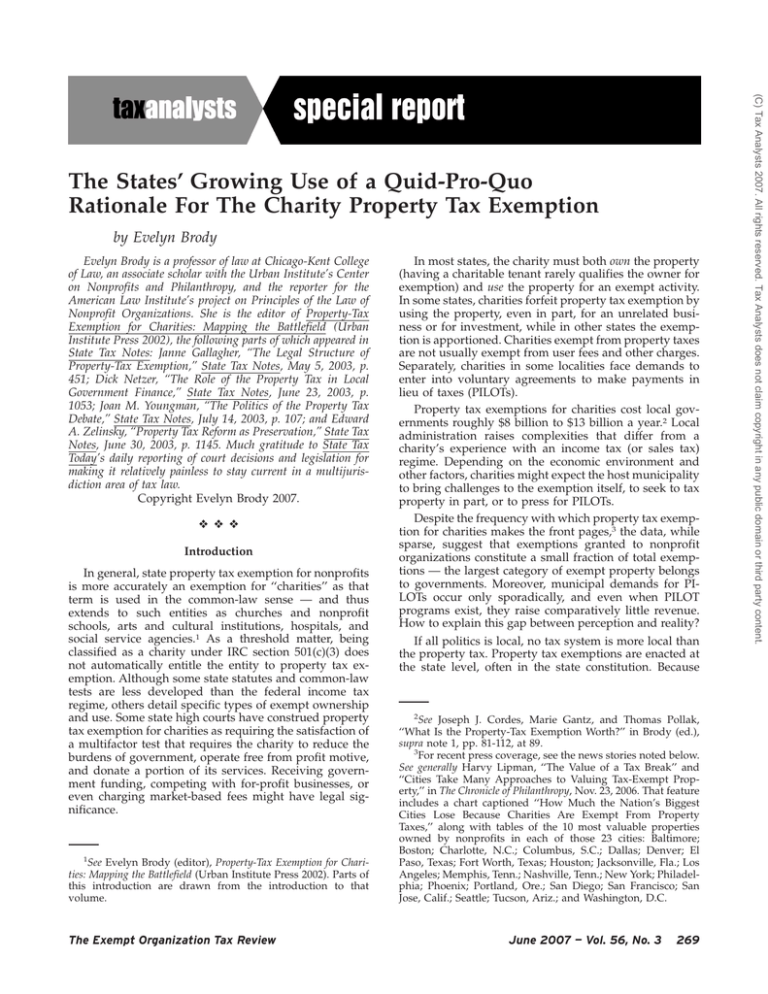

The States’ Growing Use of a Quid-Pro-Quo by Evelyn Brody

advertisement