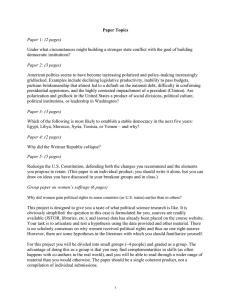

Chapter 18: The United States, an Exception or Further... A. Introduction: American Exceptions and Similarities

advertisement