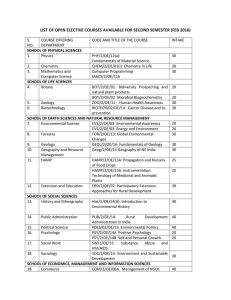

EXPERIENCE OF PEOPLE OF COLOR, WOMEN, AND LOW-INCOME HOMEOWNERS IN THE HOME

advertisement