Joint Center for Housing Studies Harvard University The Future of Manufactured Housing

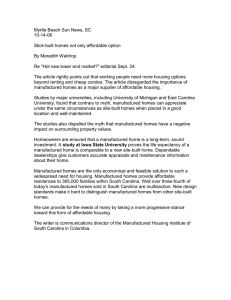

advertisement