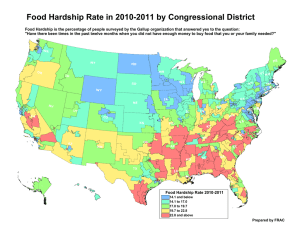

Financial Hardship before and after Social Security’s Eligibility Age

advertisement