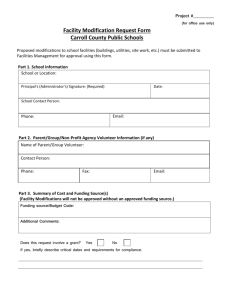

Housing Finance Policy Center Lunchtime Data Talk Mortgage Modifications Using Principal

advertisement

Housing Finance Policy Center

Lunchtime Data Talk

Mortgage Modifications Using Principal

Reduction: How Effective Are They?

Ben Keys, University of Chicago

Tess Scharlesmann, Office of Financial Research, Dept. of Treasury

Max Schmeiser, Federal Reserve Board

August 11, 2015

1

The Determinants of Subprime Mortgage Performance

Following a Loan Modification

Maximilian D. Schmeiser

Federal Reserve Board

Matthew B. Gross

University of Michigan

The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely my own and should not be

construed as representing the opinions or policy of the Federal Reserve Board, Federal

Reserve System, or any agency of the Federal government.

August 11, 2015

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

1 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Percentage of Loans Delinquent (LPS)

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

2 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Ongoing Problem of Foreclosure

As of June 2015

Nationally: 3.37% of all mortgages 90+ days delinquent or in

foreclosure (1.50% in foreclosure)

DC: 3.68% of all mortgages 90+ days delinquent or in foreclosure

(2.36% in foreclosure)

In July 2007

Nationally: 1.30% of all mortgages 90+ days delinquent or in

foreclosure (0.47% in foreclosure)

DC: 0.99% of all mortgages 90+ days delinquent or in foreclosure

(0.37% in foreclosure)

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

3 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2008

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

4 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2009

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

5 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2010

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

6 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2011

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

7 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2012

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

8 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2013

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

9 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2014

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

10 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

April 2015

Delinquent Payment: 90+ PD,Foreclosure, US, 201504*

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

11 / 40

State of the Housing Market

Mortgage Delinquency and Foreclosure Nationwide:

June 2015

Delinquent Payment: 90+ PD,Foreclosure, US, 201506*

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

12 / 40

Motivation

Motivation

Mortgage modifications have been the primary tool used to mitigate

foreclosure

Over 5 million mortgages had been modified as of Q1 2015 (OCC

2015; U.S. Treasury 2015)

68K MHA modifications and over 100K proprietary modifications

started in Q1 2015

Typical modification terms have changed over time

Passage of HAMP resulted in more standardized mods, particularly a

reduction in P&I to 31% of income

Still considerable variation in the exact terms of modifications

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

13 / 40

Research Questions

Research Questions

What modification terms are most effective at reducing the

probability of a subsequent default or foreclosure?

Change in interest rate, change in P&I, capitalization of fees and

interest, forbearance of principal, reduction of principal

Further examine how loan, borrower, and servicer characteristics, and

economic conditions affect subsequent performance

Contribution: Unique dataset (Corelogic) with detailed information on

loans, modification terms, current valuations and amount of junior

liens; national focus; examine pre- and post-HAMP mods

Limitations: Have few borrower demographics or characteristics (such

as income and employment) that could affect both modification terms

and outcomes

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

14 / 40

Background

What is a Mortgage Modification?

A mortgage modification is any change in the terms of a mortgage

Modifications relatively rare prior to recent crisis

However, magnitude of housing crisis necessitated widespread use of

modifications to help borrowers in distress

Goal of modification should be to improve affordability of mortgage

payment

Number of different options to reduce payments:

Reduce interest rate

Extend amortization period

Use principal forbearance

Reduce mortgage principal

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

15 / 40

Background

Early Mortgage Modifications

At the start of the housing crisis, modifications were at the discretion

of the servicer and terms varied substantially

Modifications made in 2008 rarely lowered monthly payments and often

resulted in increased payments

Approximately half of all subprime and alt-a mods increased payments

(White 2009)

Among all 2008 modifications done by national banks, 32 percent

resulted in increased payments (OCC 2009)

Many modifications failed to improve affordability resulting in 12

month redefault rate over 60%

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

16 / 40

Background

Post-HAMP Modifications

In March 2009 the HAMP program was introduced

HAMP required servicers to adjust monthly P&I on first lien to 31

percent of total monthly income

Follow ”waterfall” to meet target: reduce interest rate, extend term,

forbear part of principal interest free

Servicers can continue to offer proprietary modifications to borrowers

who don’t qualify for HAMP

Terms of proprietary modifications began to improve substantially

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

17 / 40

Background

Trend in Number of Mortgage Modifications

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

18 / 40

Data

Data

Use loan-level data from FirstAmerican CoreLogic’s Loan Performance

Asset Backed Securities (ABS) Data on privately securitized

mortgages

ABS data include information on subprime and alt-a loans, but does

not include information on agency backed securities or loans held in

portfolio

Data used here are only representative of privately securitized subprime

and alt-a loans, not the entire US mortgage market

Contain monthly performance history for about 20 million individual

loans

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

19 / 40

Data

Data

CoreLogic data contain detailed static and dynamic information on

the loans and their performance

Static data include information from origination such as date of

origination, the state where the property is located, the borrower’s

FICO score, origination balance, interest rate, payment and interest

amount, and servicer

Dynamic data are updated monthly and include information on the

current interest rate, mortgage balance, payment and interest, and

loan performance

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

20 / 40

Data

Data

CoreLogic also provides two supplemental files that are used in our

analysis:

The first contains detailed information on whether a borrower received

a loan modification, as well as some parameters of the modification

(e.g. reduction in principal, principal forbearance, change in P&I)

Other modification terms are inferred from dynamic loan data (e.g.

reduction in interest rate, change in amortization term)

The second file is the CoreLogic TrueLTV Data, which matches the

loans in the CoreLogic Loan Performance data to public records to

obtain information on the presence and amount of any other liens on

the property

Also contain a monthly estimate of the property’s value from their

automated valuation model

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

21 / 40

Data

Data

Given size of database select a five percent random sample of

first-lien loans

Our data on modifications and loan performance cover the period

January 2008 through December 2013

Restrict our data to loans originated no earlier than January 2000 and

modifications occurring after January 2008

To provide economic context for the loan performance we merge in

state level unemployment rates obtained from the Bureau of Labor

Statistics

Yields sample of approximately 37,000 modified loans, 1.35 million

loan-month observations

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

22 / 40

Data

Number of Modifications in Sample

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

23 / 40

Data

Share of Modifications with Payment Increase/Decrease

2008 to 2013

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

24 / 40

Data

Share of Modifications with Balance Increase/Decrease

2008 to 2013

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

25 / 40

Data

Modification Performance by Year

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

26 / 40

Data

Outcome for Modified Loans in Sample

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

27 / 40

Methods

Empirical Methods

Use two different estimation strategies: Probit for 12 month redefault

and Proportional Hazard Model estimated using a multinomial logit

The probit model takes the form:

Pr (Yizs = 1) = f (α + βXi + γModi + δCLTVi + πHPIz + θStates + izs )

Y is an indicator for whether or not the loan becomes 60 plus days

delinquent within 12 months of modification

X is a vector of loan characteristics from origination (loan used for

purchase, FICO score, owner-occupied, low or no documentation, and

origination year)

Mod is a vector of loan characteristics at the time of modification

(loan servicer, payment status, junior lien, and modification year)

Mod also includes key mortgage modification parameters (forbearance

% principal, % change in P&I, interest rate, and principal balance, %

capitalized fees and interest, HAMP mod)

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

28 / 40

Methods

Empirical Methods

In each period, a loan can be in one of numerous mutually exclusive

states: current, delinquent (30, 60, 90+ days), lis pendens, REO,

foreclosure sale, prepaid, short-sale, and modification

So estimate discrete time proportional hazard model using

maximum-likelihood to account for these various potential states

Similar specification to probit, but include time varying characteristics

current combined loan to value ratio (CLTV) and state

unemployment rate

Also include number of months since modification

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

29 / 40

Results

Results: Probit 60+ Days Delinquent within 12 months

Junior lien

Loan used for purchase

FICO at Origination 580 to 649

FICO at Origination 650 to 719

FICO at Origination 720 and Above

Not owner occupied

30 to 60 Days Delinquent at Mod

90 Days Delinquent at Mod

In Foreclosure at Mod

Year on Year Change in HPI

Unemployment Rate

Base Probability of 60 Day Delinquency:

t statistics in parentheses.

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

∗

p < 0.10,

∗∗

p < 0.05,

Mortgage Modifications

(1)

0.0284∗∗∗

(5.4123)

0.0402∗∗∗

(7.7463)

-0.0429∗∗∗

(-6.5733)

-0.1281∗∗∗

(-16.9011)

-0.2164∗∗∗

(-21.4534)

0.0328∗∗∗

(2.9566)

-0.0199∗∗

(-2.5476)

0.0892∗∗∗

(14.5294)

0.1210∗∗∗

(13.8086)

-0.0033∗∗∗

(-10.0149)

0.0142∗∗∗

(8.6610)

38.9%

∗∗∗

p < 0.01

August 11, 2015

30 / 40

Results

Results: Probit 60+ Days Delinquent within 12 months

(cont)

Principal Forbearance as Pct of Balance

Percent Reduction in Principal

Percent Capitalized Fees and Int

Percent Reduction in Interest Rate

Percent Reduction in P&I

Percent Increase in P&I

LTV 100 to 124 Percent

LTV 125 to 149 Percent

LTV 150 Percent and Above

Base Probability of 60 Day Delinquency:

Observations

t statistics in parentheses.

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

∗

p < 0.10,

∗∗

p < 0.05,

Mortgage Modifications

-0.0004∗

(-1.6578)

-0.0014∗∗∗

(-4.4665)

0.0034∗∗∗

(9.0034)

-0.0019∗∗∗

(-12.0364)

-0.0021∗∗∗

(-11.2564)

0.0011∗∗∗

(3.4191)

0.0265∗∗∗

(3.3038)

0.0451∗∗∗

(4.8195)

0.0566∗∗∗

(5.6526)

38.9%

37027

∗∗∗

p < 0.01

August 11, 2015

31 / 40

Results

Results: Multinomial Logit

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

32 / 40

Results

Results: Multinomial Logit

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

33 / 40

Results

Results: Multinomial Logit

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

34 / 40

Results

Results: Multinomial Logit

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

35 / 40

Results

Results: Multinomial Logit

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

36 / 40

Results

Results: Multinomial Logit

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

37 / 40

Conclusions

Conclusions

Any modification that improves the affordability of the loan reduces

redefault and foreclosure

Forbearance appears to reduce delinquency and foreclosure, but

magnitude is one-third that of a principal reduction

Same magnitude effect on REO

The capitalization of fees and interest significantly increases redefault

and foreclosure risk

CLTV has very large effect on subsequent redefault, foreclosure filing,

and termination in foreclosure

FICO score at origination still highly predictive of loan performance

even after a subsequent modification

Delinquency status at time of modification also highly predictive of

subsequent performance

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

38 / 40

Conclusions

Policy Implications

Principal reductions may be quite effective as they affect redefault

and foreclosure through multiple channels

Direct effect through principal reduction coefficient

Effect on P&I

Reduces CLTV

However, this does not necessarily mean they are most cost effective

modifications from the investor’s point of view

Further analysis needed to determine relative cost of each type of

modification

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

39 / 40

Contact Information

Contact Information

Maximilian D. Schmeiser

Senior Economist

Federal Reserve Board

Phone: 202-728-5882

Email: max.schmeiser@frb.gov

Schmeiser (Federal Reserve Board)

Mortgage Modifications

August 11, 2015

40 / 40

The Effect of Negative Equity on Mortgage Default

Evidence from HAMP’s Principal Reduction Alternative

Therese Scharlemann (U.S. Office of Financial Research)

Stephen H. Shore (Georgia State University)

Views expressed in this presentation are those of the speaker(s) and not necessarily of the Office of Financial Research.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Disclaimer: Views and opinions expressed are those of the

authors and do not necessarily represent official positions or

policy of the OFR or Treasury.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Overview

Research Question: By how much does reducing the

amount of negative equity – by reducing the principal

balance – reduce mortgage default?

Data: Administrative data on HAMP PRA, a governmentsponsored program for delinquent borrowers.

Method: Exploit ‘quasi-experimental’ variation in amount of

principal forgiveness granted under HAMP PRA program

rules

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Preview of Results

Default ≡ program exit after 90+ days delinquency

Principal forgiveness averages 28% of principal balance

Observed quarterly default hazard: 3.1%

Counterfactual hazard absent PF: 3.8% (CI: 3.5-4.1%)

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Why might negative equity matter for default?

Neg equity → paying a price that is higher than realized

value

Vulnerable to economic shock; cannot sell home to satisfy

mortgage balance.

Holding current costs and benefits of defaulting constant

(e.g., monthly mortgage payment, home value, home price

expectations, etc).

Principal forgiveness increases future expected benefits of

not defaulting today.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP)

Government program to help delinquent borrowers

Voluntary for servicers/lenders with government subsidy

Delinquent borrowers are sent a letter about HAMP

Qualified borrowers can apply for a HAMP modification

Standard HAMP modifies mortgage terms until the

mortgage is affordable to the borrower

modification: reduce payments by reducing interest rate,

extending loan terms, and/or forbearing principal

affordability target: 31% debt-to-income (DTI) ratio

temporary: rate subsidies phase out beginning in 5 years

NPV test to ensure that modification benefits lender

Borrower completes 3 month trial period at their new

payment to receive "permanent modification".

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

HAMP PRA

HAMP Principal Reduction Alternative (PRA) modification

also includes principal forgiveness (PF)

same affordability target as Standard HAMP

LTV target: 115% LTV target (for 85% of loans) or a 100%

LTV target (for 15% of loans)

servicers with 100% LTV target limit PF to 30% initial UPB

Applicants may be offered Standard HAMP or HAMP PRA

Test to determine NPV to lenders. Servicers typically offer

modification (or no modification) with highest NPV.

3 month trial period at new payment

Program officially in place October 2010.

Enrollment

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Standard HAMP and HAMP PRA Waterfalls

Waterfall continues until borrower hits affordability target of

DTI=31%

Standard

HAMP

no reduction

in mortgage balance

HAMP

PRA

reduce mortgage balance

to hit LTV target

typically 115% LTV

reduce interest rate to 2%

extend loan term to 40 years

forbear principal as needed

equivalent to zero rate balloon

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Data overview

Administrative records for all new permanent HAMP

modifications enrolled 1/2011-6/2013.

45,513 loans, 244,132 loan-quarters

First cohort observable for 10 quarters.

Outcome variable of interest: 90-day delinquency

Borrowers disqualified from program if 90 days delinquent

HAMP database does not track final resolution

Measure default as quarterly hazard: new defaults as

share of surviving loans in each quarter.

Loans in sample have completed 3-month trial and

become permanent

Cannot reliably see mortgage characteristics of cancelled

trials.

About 10 percent of trial modifications are cancelled before

they become permanent - about 2/3rds due to nonpayment.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Identification – Regression Kink Design (RKD)

LTV

Principal Forgiveness (PF) ≡ Initial

Final LTV − 1

= max{0, min{amount needed to hit DTI target,

amount needed to hit LTV target}}

PF needed to hit DTI target (PFDTI ):

PF needed to hit LTV target (PFLTV ):

Initial Mortgage DTI

Target Mortgage DTI

Initial LTV

Target LTV − 1

−1

Servicers with LTV target 1̄00% cap PF at 30% initial UPB.

Can control flexibly for LTV and DTI terms separately

LTV = loan-to-value (measures negative equity)

DTI = debt-to-income (measures ability to pay)

Total DTI = Mortgage DTI + Fixed DTI (taxes and insurance)

Target Mortgage DTI = 31% - Initial Fixed DTI

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Final LTV (red)

Identification (Moderate Initial DTI)

DTI limits PR

45º

LTV Target

PR

nt

u

o

Am

Initial LTV

Source: Authors’ analysis

Appendix

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Final LTV (red)

Identification (High Initial DTI)

DTI limits PR

45º

LTV Target

PR

nt

u

o

Am

Initial LTV

Source:Authors’ analysis

Appendix

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Cap limits PR

45º

LTV Target

PR

nt

u

o

m

A

DTI Would

Have Limited PR

Final LTV (red)

Identification (PRA-cap Kink)

Initial LTV

Source: Authors’ analysis

Appendix

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Identification: empirical model

Pr(Default) = f (α + βPF ln (1 + PF)

+ βLTV ln(1 + PFLTV )

+ βDTI ln(1 + PFDTI )

+ βX X + ε)

We are comparing the relationship between LTV and default on

either side of the kink.

RK treatment effect is calculated as the change in the slope at the

kink (βPF ) divided by the change in the first derivative of the

treatment at the kink (in this case, 1).

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Identification: Selection

PF allocation: We predict PF very well. R 2 in first-stage

regression is 0.99, with precise coefficient of 0.99.

Kink design: Difficult to argue that amount of PF is

correlated with unobservable propensity to default

(conditional on LTV, DTI, and servicer).

Selection: Do servicers select borrowers into PRA with

unobservably higher (or lower) propensity to default when

those borrowers would get higher PF amounts?

Servicer selection on unobservables is difficult for services

because they must follow rules based on observables.

Borrower selection at application on unobservables unlikely

given kink design (borrowers don’t know on which side they

will land when they apply)

Borrower selection possible between receiving trial

modification or offer and before permanent modification

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 1: Impact of Principal Forgiveness on Hazard (Logit)

Dep. Var.

ln(1+PF)

ln(1 + PFLTV )

ln(1 + PFDTI )

Dummy for LTV target = 115 percent

Quarters of observation controls

Quarter cohort and servicer dummies

DTI before modification

Interaction variable

Other controls

10-ppt LTV and DTI bins

Observations

Loans

R2

-0.85***

(0.13)

0.38***

(0.09)

-1.07***

(0.05)

YES

YES

NO

NO

NO

NO

NO

244,132

45,513

0.0289

Quarterly exit rate

-0.54***

-0.61***

-0.65***

(0.13)

(0.14)

(0.16)

0.23**

0.11

0.55***

(0.09)

(0.11)

(0.13)

0.42***

0.31***

0.26**

(0.05)

(0.08)

(0.10)

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

NO

YES

YES

NO

NO

YES

NO

NO

NO

244,132

244,132

211,409

45,513

45,513

39,310

0.0520

0.0520

0.0808

-0.87***

(0.25 )

-0.16

(0.67 )

1.77**

(0.73)

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

210,712

39,172

0.0826

(All specifications include an LTV target control and quarters-of-observation dummies. "Other Controls": FICO, ARM dummy,

investor-owned mortgage dummy, log income, log pre-mod balance, length of trial (linear and squared), log NPV of HAMP mod over no

mod, log NPV of HAMP PRA mod over no mod, dummy for whether the standard HAMP mod had a higher NPV than the PRA mod.)

Source: Authors’ analysis.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Context for Results

Logit coefficient for ln(PF) to predict the quarterly hazard is

-0.54 to -0.87.

The average quarterly hazard is is ∼ 3.1% for the HAMP

PRA loans in this sample.

A 10% PF at mean implies 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points

drop in the quarterly hazard rate (e.g., from 3.8% to 3.5%

or 3.6%).

The average PF of 30% implies a drop in the quarterly

hazard rate from 3.8% to 3.1%

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Counterfactual: Cumulative default with and without PF

Cumulative Default Rate by Quarter of Modification

0.60

‐ Average hazard with PR: 3.1%

‐ Average hazard without PR: 3.8% ‐ Confidence inverval: [3.5%,4.1%]

0.50

0.40

0.30

0.20

0.10

0.00

2011:Q12011:Q22011:Q32011:Q42012:Q12012:Q22012:Q32012:Q42013:Q12013:Q2

Quarter of Modification

Proportion of modifications that have exited through 2003:Q1 (green line)

Counterfactual proportion of modifications exiting through 2013:Q1 (blue line)

Green – Observed Rate

Blue – Counterfactual Rate Absent Principal Forgiveness

Source: Authors’ analysis

Appendix

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Figure: Estimates for 115 LTV Target Sample

0.45

0.35

Principal forgiveness increases with pre‐modification LTV. Post‐modification LTV unchanged as LTV increases.

Principal forgiveness unchanged as pre‐

modification LTV increases. Post‐modification LTV increases with pre‐modification LTV.

0.25

0.15

0.05

‐0.05

‐0.15

‐0.7 ‐0.6 ‐0.5 ‐0.4 ‐0.3 ‐0.2 ‐0.1

0

0.1

ln(PFLTV) ‐ ln(PFDTI)

Source: Authors’ analysis

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 2: Impact of Principal Forgiveness, kink analysis (logit)

Dep. Var.

Sample

ln(1 + PF )

ln(1 + PFLTV ) PR

ln(1 + PFDTI )

Observations

Loan count

R2

Source: Authors’ analysis

Full

-0.851***

(0.129)

0.380***

(0.089)

-0.539***

(0.031)

244,132

45,513

0.029

Quarterly exit rate

Uncapped

Kink ≤ 0.5

-0.748***

-0.566**

(0.145)

(0.225)

0.308***

0.112

(0.105)

(0.138)

-0.479***

-0.451***

(0.039)

(0.043)

216,407

143,851

41,339

27,641

0.0308

0.0213

Kink ≤ 0.25

-0.421

(0.519)

-0.242

(0.307)

-0.448***

(0.056)

83,913

16,200

0.0182

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 3: Placebo tests

Dep. Var.

Sample

ln(1+PF)

ln(1 + PFLTV )

ln(1 + PFDTI )

Full

-0.851***

(0.129)

0.380***

(0.089)

-1.072***

(0.045)

ln(placebo PF)

Dummy for LTV target = 115

Quarters of observation controls?

Full set of controls?

Observations

Loan count

R2

YES

YES

NO

244,132

45,513

0.029

Quarterly exit rate

Full

Full

Placebo

-0.911***

-0.920***

0.084

(0.133)

(0.264)

(0.128)

0.328***

-0.121

0.343***

(0.094)

(0.675)

(0.085)

-1.114***

1.828**

-1.658***

(0.052)

(0.737)

(0.044)

0.282*

-0.124

(0.144)

(0.252)

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

NO

YES

NO

244,132

210,712

293,962

45,513

39,172

52,862

0.039

0.083

0.042

Placebo

-0.035

(0.225)

0.351

(0.539)

0.231

(0.609)

YES

YES

YES

278,298

48,378

0.080

("Full controls": cohort and servicer dummies, DTI before mod, DTI and LTV bins, FICO, ARM dummy, investor-owned mortgage dummy,

log income, log pre-mod mortgage balance, trial mod length (linear and squared), log NPV of HAMP mod over no mod, log NPV of

HAMP PRA mod over no mod, and a dummy indicating a standard HAMP mod had a higher NPV than a HAMP PRA mod.)

Source: Authors’ analysis

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Figure: Within Estimates for 115 LTV Target Sample - Placebo

0.45

0.35

Principal forgiveness increases with pre‐modification LTV; Post‐modification LTV unchanged as LTV increases

Principal forgiveness unchanged as pre‐

modification LTV increases; Post‐modification LTV increases with pre‐modification LTV

0.25

0.15

0.05

‐0.05

‐0.15

‐0.25

‐0.35

‐0.7 ‐0.6 ‐0.5 ‐0.4 ‐0.3 ‐0.2 ‐0.1

0

0.1

ln(PFLTV) ‐ ln(PFDTI)

Source: Authors’ analysis

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Conclusion: Comparison with Existing Benchmarks

Logit coefficient for ln(1 + PF) to quarterly hazard is -0.54

to -0.87.

The average quarterly hazard is ∼ 3.1% for HAMP PRA.

∼ 30% PF reduces average hazard from 3.8% to 3.1%.

∼ 30% PF reduces cumulative default rate from 49% to

39% in earliest cohort.

Impact of PF may not remain constant over time.

Modifications with rate reduction get less generous after 5

years, so a spike in default for lower-PF (higher rate

reduction) modifications is possible.

Improvements in the housing market may make principal

forgiveness less important.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Conclusion: A simplified discussion of costs vs. benefits of PF

Cost of PF: 30% × (1 − lifetime re-default rate)

Benefit of PF: (lifetime change in re-default rate) ×

(difference between modified & recovery values)

Cost-effectiveness of PF will increase/decrease if:

default-reducing benefits of PF grow/narrow over time

and/or

Counterfactual default rate increases/decreases.

First cohort: change in default rate implies $877k in

writedowns per avoided foreclosure.

Ten loans written down for every avoided foreclosure.

Government subsidy of $262k per avoided foreclosure.

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Evidence of bunching: Loans whose servicers do not apply cap

Distribution of PRA Recipients Not Subject to Cap

0

.2

.4

Density

.6

.8

1

by Distance from Kink

-1

0

1

Distance from Kink

2

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Evidence of bunching: Loans whose servicers apply cap

Distribution of PRA Recipients Subject to Cap

0

.5

Density

1

1.5

2

by Distance Between Uncapped and Capped PRA Amounts

-.4

-.2

0

.2

.4

Distance Between Uncapped and Capped PRA

.6

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Context for Results

Cost of PF:

(PF amount) ×(1 − permanent default rate)

Benefit of PF: (permanent change in default rate) ×

(severity of loss in default, e.g. 50% of mortgage)

∼ 30% PF reduces average hazard from 3.8% to 3.1%.

∼ 30% PF reduces cumulative default rate from 49% to

39% in earliest cohort.

To be cost effective absent subsidies or externalities

default-reducing benefits of PF would have to grow over

time relative to the baseline default rate and/or

baseline lifetime default rate would have to be very high

absent PF

return

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Figure 2: HAMP Enrollment

Cumulative enrollment of non‐GSE loans from Jan 2011 ‐ Dec 2012 Thousands

300

HAMP with Principal Reduction

Standard HAMP

250

200

150

100

50

0

Jan

Mar

May

Jul

2011

return

Sep

Nov

Jan

Mar

May

Jul

2012

Sep

Nov

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 1: Summary Statistics About Loans and Borrowers

Balance pre-mod (0 000s)

Home value (0 000s)

Gross monthly income (0 000s)

Total mortgage payment (0 000s)

Principal & interest payments (0 000s)

FICO

N

(0 000s)

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

41.8

Med.

Mean

SD

Min

Max

$292

$180

$4.5

$2.0

$1.6

559

$324

$205

$4.9

$2.2

$1.8

568

$173

$118

$2.39

$1.05

$0.90

69

$18

$10

$0.6

$0.3

$0.2

250

$1,279

$856

$22.2

$9.5

$9.0

839

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 2: Summary Statistics About Modifications

Total DTI pre-mod

Total DTI post-mod

Total payment reduction

LTV before modification

LTV after modification

Principal balance reduction

Rate pre-mod

Rate post-mod

Term pre-mod (months)

Term post-mod (months)

N

(0 000s)

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

45.5

Med.

Mean

SD

Min

Max

44.2%

31.0%

29.8%

158.8%

115.0%

28.2%

6.4%

3.0%

305

301

47.0%

31.0%

30.0%

164.2%

121.2%

28.9%

6.3%

3.9%

317

333

12.3%

0.4%

16.0%

33.5%

16.1%

17.4%

2.0%

2.1%

60

76

24.0%

12.4%

0.0%

109.8%

100.0%

0.0%

0.8%

1.0%

1

12

100.0%

33.0%

69.0%

240.0%

237.7%

73.5%

15.1%

15.0%

541

541

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Figure: Treatment for 115 LTV Target Sample

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 4: Impact of PF, Between and Within Estimates

Dep. Var.

Sample

Identification

ln(1+PF)

ln(1 + PFuncapped )

ln(uncapped PF) ln(capped PF)

ln(1 + PFLTV )

ln(1 + PFDTI )

ln(LTV initial)

LTV bin x PRA from DTI bin

Observations

Loan count

R2

Quarterly default rate

Full

LTV Target of Sample

Sample

115%

100%

Full

Between

Within

Within

-0.851***

-1.130***

-0.615***

(0.129)

(0.224)

(0.163)

-0.925**

(0.387)

-0.486

(0.481)

0.380***

0.182

0.688***

(0.089)

(0.124)

(0.183)

-1.072***

0.577

-1.184***

-0.777***

(0.045)

(0.659)

(0.058)

(0.115)

0.502

(0.670)

No

Yes

No

No

244,132

244,132

200,146

43,876

45,513

45,513

38,513

7,000

0.0289

0.0332

0.0261

0.0209

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 7:Estimates in subsamples (logit)

Dep. Var.

Sample

ln(1+PF)

ln(1 + PFLTV )

ln(1 + PFDTI )

Dummy for LTV target = 115

Quarters of observation controls?

Observations

Loan count

R2

Full

-0.851***

(0.129)

0.380***

(0.089)

-1.072***

(0.045)

YES

YES

244,132

45,513

0.0289

Quarterly exit rate

ARM

FRM

PLS

-0.945***

-0.771***

-0.796***

(0.210)

(0.167)

(0.165)

0.504***

0.352***

0.518***

(0.145)

(0.115)

(0.108)

-0.842***

-1.146***

-1.053***

(0.071)

(0.063)

(0.056)

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

YES

105,265

138,867

146,271

18,867

26,646

29,412

0.0225

0.0322

0.0336

Portfolio

-0.728***

(0.218)

0.144

(0.161)

-1.099***

(0.079)

YES

YES

97,861

16,101

0.0247

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Table 6: Variation in estimates (logit)

Dep. Var.

ln(1+PF)

ln(1+PF)

x ln(initial TDTI)

ln(1+PF)

x quarters since mod

quarter of mod

-0.851***

(0.129)

-0.228

(0.325)

0.487

(0.349)

Quarterly exit rate

-0.817*** -0.924***

(0.187)

(0.203)

-0.010

(0.039)

-0.095***

(0.013)

ln(1+PF)

0.039

x quarter of mod

(0.045)

Dummy for LTV target = 115

YES

YES

YES

YES

Quarters of observation controls?

YES

YES

YES

YES

Observations

244,132

244,132

244,132

244,132

Loan count

45,513

45,513

45,513

45,513

R2

0.029

0.039

0.029

0.031

NB: ln(Predicted PF)≡ ln(Pre-Mod LTV)− ln(Predicted Post-Mod LTV)

-0.950***

(0.284)

0.006

(0.041)

-0.096***

(0.014)

0.041

(0.047)

YES

YES

244,132

45,513

0.031

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Counterfactual: hazard by modification duration, with and without

PF

Hazard by Quarters Since Modification

(Quarterly rate of exit from program)

0 06

0.06

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0.00

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Quarters since Modification

8

Observed hazard (green)

Counterfactual hazard absent principal reduction (blue)

9

10

Motivation

HAMP

Identification

Results

Conclusion

Appendix

Counterfactual: hazard by calendar quarter, with and without PF

Hazard by Calendar Quarter

(Quarterly rate of exit from program)

0.07

0.06

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0.00

2011:Q2 2011:Q3 2011:Q4 2012:Q1 2012:Q2 2012:Q3 2012:Q4 2013:Q1 2013:Q2 2013:Q3

Calendar Quarter

Observed hazard (green line)

Counterfactual hazard absent principal reduction (blue line)

Mortgage Modifications using Principal

Reduction: How Effective Are They?

Ben Keys

Harris School of Public Policy

University of Chicago

August 11, 2015

What we talk about when we talk about

mortgage modification

• Goals:

• Help struggling homeowners continue to maintain consumption

• Effect of losing $5 trillion (!) in home equity

• Avoid foreclosure by “curing” delinquent borrowers

• Prevent neighborhood-level spillovers from neglect/abandonment

• Campbell, Giglio, and Pathak (2011)

• Why do homeowners default?

• Income disruptions or shocks to liquidity

• Bad underwriting or contract-related shocks

• Strategic incentives to “walk away” when sufficiently underwater

• Bhutta, Dokko, and Shan (2010) suggest relevant only when LTV>150%

Key Research Questions

• How do we help homeowners stop the transition from

default to foreclosure?

• These papers unpack the mechanisms of modification effectiveness

• Are modifications cost-effective?

• Huge costs to the government to facilitate modifications

• Depends on which features are used (e.g. principal reduction)

• Depends on how we estimate the benefits

• Are principal reductions the solution if temporary income

disruptions are the problem?

Schmeiser and Gross (2015)

• Data from CoreLogic on subprime and Alt-A loans

• Modifications between 2008 and 2013 (HAMP and non-HAMP)

• Many mods increase principal balance by rolling in fees/interest

• Almost 20% of mods increase payments (!) through post-due capitalization

• Hazard model approach to estimate impact of modification

features on re-default

• Baseline characteristics at time of modification matter a lot

• Delinquency status, FICO and especially CLTV

• Forbearance effect is 1/3 that of principal reduction

• Principal reduction helps through multiple channels

• Reduces CLTV (strategic incentive)

• Reduces monthly payment at same time

Challenges for Studying Modification

• Size and elements of modification are endogenous to pre-

modification characteristics of borrower and housing market

• e.g. why is initial CLTV so predictive of subsequent default?

• Strategic default, or

• Homeowners who reached high CLTV did so through low down payments,

bad contracts (e.g. NegAm), or aggressive extraction combined with

negative regional shocks

• Servicers may be strategically selecting those loans most

likely to succeed

• Results are conditional on choice to modify

• Servicers can design their own program or opt into HAMP program

Scharlemann and Shore (2015)

• Use data from HAMP PRA program and kinks in program design

used to determine amount of principal forgiveness

• Non-GSE loans enrolled in 2011-2013: $3.8b in total forgiveness

• Average loan receives 28% reduction in principal

• Kinks in design affect different borrowers in terms of the amount of

principal reduction

• Based on distance from kink in principal reduction schedule

• Avoids endogeneity problems

• Requires assumptions about similar borrowers on either side of the kink,

and relatively farther away as well to estimate slopes

• Useful placebo test where default increases monotonically in pre-mod LTV

• Cost estimate: $877,000 per foreclosure avoided (!)

• Cost to government: $262,000 per foreclosure avoided

Placebo test figure nails effect of PRA:

Consensus View:

Larger Payment Reduction, Fewer Defaults

• This is true almost by construction

• Need a better understanding of why people default in order

to target modifications and modification features

• If people are liquidity constrained, reducing principal with no change

in payment should not matter on the margin

• Only affects wealth, not liquidity

• Holy grail of data: 1)Debts, 2)Assets, 3)Income, 4)Consumption

• If we knew more about income shocks, we could better design

temporary assistance programs

• If we knew more about consumption, we can see whether programs

had their intended effect outside of the mortgage contract alone

Efficient Credit Policies in a Housing Debt Crisis

• Eberly and Krishnamurthy (BPEA 2014) model:

• Government’s priority should be helping cash-strapped homeowners

• 1) Maintain spending in a weak economy

• 2) Avoid foreclosures

• Some role for principal reduction to reduce strategic default motives

• But costly and spreads benefits over much longer period of time

• Much larger role for temporary efforts to lower monthly payments:

• Defer/forbear mortgage payments

• Reduce interest rates

• Extend mortgage terms

• Propose redesigning mortgages with automatic adjustments

• “Allow for disproportionately lower payments when borrowing constraints bind”

Concluding Thoughts

• Two fantastic examples of careful empirical work to answer

hugely important policy question

• Building consensus around view that principal forgiveness

received limited bang for its buck

• Alternatives

• Large-scale forbearance and refinancing programs

• Automatic refinancing contracts

• Letting some homeowners fail in a low-cost way (own-to-rent?)

• Final note that mortgage programs missed some of the neediest

households

• e.g. NPV-negative because unemployed, failed trial mod, failing to take-

up HARP

More notes on Schmeiser and Gross

• Unemployment rate coefficient is negative in paper (positive in slides)

• MNL results on unemployment and HPI flip sign depending out mortgage

outcome, this is puzzling

• How to think about static vs. time-varying characteristics

• Most importantly CLTV, HPI, and unemployment rate

• Why are HAMP modifications more effective even after conditioning

on terms?

• Has to be something about selection, right?

• Or omitted variables?

• Can be more up-front about endogeneity concerns

More notes on Scharlemann and Shore

• Introduction undersells the result

• Doesn’t fully explain how important the finding is or put it in a broader context of the literature, and

varies across too much detail and too little

• Identification could use a clearer simpler example

• Terms of forbearance: How long does it last? 5 years?

• Why does PRA have the “reverse waterfall” relative to HAMP? How does 2MP fit in?

• Median FICO at time of modification is only 560: Should we expect any of these

people to cure?

• Why are the signs different on PF from LTV and PF from DTI?

• Shouldn’t a dollar in PF be a dollar regardless of where it comes from? This is still unclear

• Is counterfactual exercise of no principal forgiveness but same payment reduction

way out of sample?

• Is this all just substituting forgiveness for forbearance?