for Invasion: Competition Prospects Between

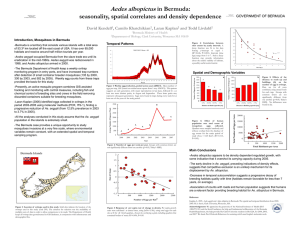

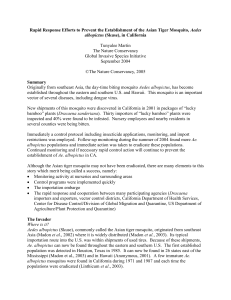

advertisement

Prospects for an Invasion: Competition Between Aedes albopictus and Native Aedes triseriatus in which N. represents the initial number of females, A, the number of females emerging on day x, and wx the mean winglength of females emerging on day x;flw,) predicts numbers of female offspring based on female body size; and D is an estimate of the delay between female emergence and first oviposition. Separate studies of individual females, offered blood daily after emergence, TODD P. LIVDAHL AND MICHELLE S. WILLEY Competition between larval populations of the native North American treehole mosquito Aedes triseriatus and Aedes albopictus, recently introduced from Asia to North America, was assessed by comparing per capita growth rate estimates for experimental cohorts of larvae developing under a variety of initial density combina- provide estimates of D 11.9 days for A. tions in fluid obtained from tires or from treeholes. Estimates of carrying capacities triseriatus and D = 14.2 days for A. albopicand competition coefficients indicate that competition between the two species will tus. Linear functions describe size-depenresult in stable coexistence in treehole communities but local extinction of A. dent fecundity: j(wx) = 23.2w. - 51 for triseriatus in tire habitats. A. triseriatus (r2 = 0.38) and ftwx) = 17.2wx- 14 (r2 = 0.03) for A. albopictus EDES ALBOPICTUS, A CONTAINERined competition between A. albopictus and (10). breeding mosquito, has begun to A. triseriatus, a common filter-feeding and Regression of r' on the initial densities of colonize the North American conti- browsing inhabitant of treeholes and tires A. triseriatus and A. albopictus can be exnent during the last several years, after its throughout the eastern United States (5), to pressed in the form introduction within imported used automo- determine whether A. triseriatus can prevent bile tires. Successful colonization by this the establishment of this ecologically similar dNi i rm + biNi (2) bjNj potential vector for disease transmission, species. Previous comparisons of separate most notably dengue fever (1), and which aspects of single and mixed species cohorts occupies much of Asia and the Pacific re- using artificial media in jars, tires, and When (rTm + bNi + bNj) is set equal to gion, was first observed in Houston in tons enable predictions that interactions of zero and Nj is plotted as a function of N., 1985, where it had already achieved domi- A. albopictus with resident species may result the result is a line that defines the combinance in artificial containers (2). Aedes atin a long-term establishment in tires (6). nations of initial densities that result in no bopictus has since become widespread, occurEggs obtained from laboratory colonies population growth for species i, the zero ring in much of the southeastern and into of A. albopictus and A. triseriatus (7) were growth isocline (Fig. 1). Density combinathe midwestern United States (3). The in- hatched 24 hours before the experiment. tions falling below an isocline permit controduction of A. albopictus has public health Larvae of each species were disbursed, in all tinued growth of the species associated significance, and the ecological outcome of density combinations of 7, 14, 28, and 42 with that isocline; density combinations this introduction will enhance our under- with single species controls for each density, above an isocline will result in the species' standing of community structure. Successful into uncovered 120-mi plastic cups contain- decline. establishment of A. albopictus without the ing 0.5 g of dried leaf litter and 100 mI of In treehole fluid (Fig. 1A), the isoclines displacement of native filter-feeding and treehole or tire fluid, depending on the intersect at positive densities for both spebrowsing species will imply that evolution- habitat treatment (8). For treehole simula- cies; long-term interaction between these tions, 25 ml of fluid was replaced weekly species should therefore result in their conary niche diversification in response prolonged competition between larval stages is with fresh tree drainage water (stemflow), tinued coexistence in treeholes. In tire fluid not necessary for the coexistence of ecolog- collected with a slit hose caulked about a (Fig. LB), the isoclines do not intersect at a ically similar species. maple tree. Both habitat simulations re- positive density for A. triseriatus; long-term Aedes albopictus has demonstrated an apti- ceived weekly replacement of evaporated association between these species should tude for rapid colonization of artificial water with distilled water. Experimental result in the competitive exclusion from tires maintained in aquatic larval habitats, such as discarded populations of A. triseriatus by A. albopictus. insectary automobile tires (3). Egg diapause respons- (220 + IC, -70% relative humidity, and The Lotka-Volterra model of two-species es to photoperiod and freezing tolerance 16 hours light:8 hours dark photoperiod). competition provides a useful starting point indicate that A. albopictus immigrated from Three replicates were raised for each two- for the analysis of this interaction, in which temperate Japanese populations (4) species density combination and five repli- the per capita rate of change for species i is a preadapted for physical conditions in much cates of all single-species density levels. Pu- direct analog of Eq. 2 of North America. Despite its colonizing pae were removed from experimental r.m dNi rmiay ability and tolerance of physical conditions, habitats and placed within vials of water (3) the eventual success of A. albopictus may topped with inverted vials. Adults were reK, N Ntdt 'i Ki hinge on its ability to interact with native moved daily; female wings were measured at Within this framework, the stability of the magnification x25. species within communities under invasion, Per capita growth rates were estimated for interactions depends on a combination of particularly the mosquitoes that occupy treeall larval cohorts from the composite index the competition coefficients (a%), which holes and tires in eastern North America. This experiment addresses the potential (9) convert the per capita influence of species j on the growth rate of species i into the for competitive success of A. albopwtus as a colonist of two habitats, tires and waterequivalent number of species i and carrying InL Axf(wx)] filled treeholes, both of which maintain wellcapacities (Ks). These quantities are calculat(1) ed indirectly from the intercept and regresdeveloped native mosquito fauna. We examsion coefficients of Eq. 2. D + x x The difference in the predicted outcome of Clark Department Biology, University, Worcester, for the two fluids is clarified by comparing MA 01610. = A = + car- to were an [.XAxf(wx)yiAxf(wx) 12 JULY 1991 REPORTS 189 with A. albopictus at very low densities. Sufficient time may not have elapsed since the introduction of A. albopictus to enable s abo g B|A. gi '0@ | 80 lsdln. 01 8 the test of these predictions in field popula1 tions, but coexistence between A. albopictus and A. triseriatus within treehole communi10 to 60 oCD0 60 0 01 ties is suggested by the appearance of A. triseriatus and A. albopictus as the first and Atdsertafus ~ A tisea~ J1 second most abundant filter-feeding species 0 4 in glass jars attached to trees in a Louisiana forest (14), making up 81% and 17% of the z z5 filtering and browsing larvae collected. The co-occurrence of these two species has also been noted in other studies of treehole 40 0 20 60 80 100 40 20 60 0 80 100 communities (15). Field studies of A. alNo. of A albopictus per 100 ml No. of A albopitus per 100 ml aegypti in artificial habitats, with A. bopictus Fig. 1. Density combinations that permit equilibrium for Aedes triseriatus and A. albopictus. Hatched regions overlay combinations for each species for which the 95% confidence interval of the predicted tires in Texas (2) and cemetery vases in per capita rate includes zero in (A) treehole and (B) tire-simulated habitats. The equilibrium Florida (15), suggest success byA. albopictus combination of densities is circled for each fluid treatment. Differences between the intercepts of the as a competitor in such containers, with a two isoclines are statistically significant on both axes in treehole fluid and on the vertical axis in tire fluid concomitant reduction ofA. aegypti popu(P < 0.01 in each case); the difference between intercepts on the horizontal axis in tire fluid is not lations. Aedes triseriatus is only abundant in significant. Standard errors for these t tests were obtained with the jackknife technique (11). tire habitats located within shaded areas, and few detailed census data are available for K. and ag in each fluid for each species (Fig. significant and opposite differences in a,7's such habitats in areas that have been reached 2). The difference does not result from for the two species. If these coefficients by dispersing A. albopictus. However, the altered Ks's alone, which are significantly reflect overlap of resource. use, the differ- potential for A. albopictus to dominate artilower in tire fluid for both species, reduced ences suggest that resources exist within ficial habitats has been clear since its discovby nearly the same amount for each. The tires that can be used much more effectively ery in Texas, where A. albopictus' abundance weekly addition of nutrients and removal of by A. albopictus than A. triseriatus, and that was three times that of A. aegypti and 20 metabolic wastes by replacing 25 ml with treehole fluid contains resources that each times that of A. triseriatus (2). Although A. triseriatus may be the most stemflow in treehole fluid may account for species exploits differentially. Detailed studies of the larval diets of these two species in likely potential treehole competitor, other much of this difference in Ki. The differential competitive outcome in the two habitat types should be informative. treehole species might interact with A. alThis analysis could be enhanced by the bopictus. Differences among filter-feeding the two fluid types results primarily from incorporation of a wider variety of initial species in vulnerability to the predatory densities of the two species, which would mosquito larva Toxorhynchites rutilus in the 60 r permit tests for nonlinear concave responses Southeast could influence the outcome of to density, known to occur in A. triseriatus theA. albopictus invasion. Additional species 50sh growing in an artificial medium (11), as well of potential importance to the establishment Ka-as nonadditive interactions between the of A. albopictus in treehole communities K + 3.19m However, the narrow isocline include Anopheles barberi, a potential filtercompetitors. 40 regions defined by the linear model for A. feeding competitor that becomes a facultaKt triseriatus in treehole fluid suggest that non- tive predator on small larvae during its 2.73' 30 L linear isoclines resulting from such nonlin- fourth instar (16), and three additional filear models should not vary substantially ter-feeding and browsing species: Aedes 1.0 from this linear case, leaving intact the pre- hendersoni, Orthopodomyia signfera, and 0. -2.29* diction of coexistence. More likely, our pre- alba. However, all four of these potential _ _ 1.. i _ 0.6 diction of competitive exclusion of A. trise- competitors have marked preferences for a riatus in tire fluid may require modification restricted types of treeholes (5), and are 0.4 CL at 4.88* to include the possibility of its coexistence therefore unlikely to present consistent ob02 J1 J1 q J1 1-. - Tire Trehoie Fluid ource Fig. 2. Comparisons of parameters of competiantd K. depict tion in treehole and tire fluid. carrying capacities forA. triseriatus an dA. albopictus. Competition coefficients translate the competitive effect of an A. albopictus indiviidual on A. tnseriatus into the equivalent number ofA. triseriatus individuals (ama), and the revers(e translation (acL). Standard errors for each estimaLte, obtained with the jackknife technique (11), mre shown as vertical bars. The t statistics for diifferences of parameters estimated for treehole arnd tire fluid treatments are shown (*P < 0.05, * *P < 0.01). 190 Table 1. Responses of per capita growth rate estimates for each species to the initial density of Aedes triseriatus and A. albopictus larval cohorts in two types of fluid. Regression analyses are based on Eq. 2. Standard errors for each regression term and the coefficient of determination (r2) are shown. All regression coefficients are statistically significant (P < 10`-). Units are as follows: rm, days'-; b1 and b2, days-' x (individuals/100 ml)-1. The numbers of r' values obtained for each regression (n) differ because some cohorts produced no survivors, especially A. triseriatus growing at high densities in tire fluid (10). Fluid Species n rm b2 bi 0.0029 -0.0012 ± 0.0001 -0.0005 ± 0.0001 0.74 Treehole triseriatus 65 0.0514 + albopictus 64 0.0798 ± 0.0036 -0.0015 triseriatus 35 0.0591 + 0.0070 -0.0018 Tire albopwtus 65 0.0904 + 0.0036 -0.0020 + + + 0.0001 -0.0011 0.0003 -0.0015 0.0001 -0.0005 + + + 0.0001 0.80 0.0003 0.66 0.0001 0.82 SCIENCE, VOL. 253 stacles to the establishment of A. albopictus; a large fraction of treeholes contain only A. triseriatus as potential competitors (5). Our results indicate that competition with the predominant species in treehole communities, A. triseriatus, will be insufficient to prevent the establishment of A. albopictus. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. REFERENCES AND NOTES D. ShroyerJ. Am. Mosq. Control 2, 424 (1986). D. Sprenger and T. Wuithiranyagool, ibid., p. 217. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. Newsl. 16 (no. 3), 13 (1990); ibid. 16 (no. 2), p. 5; ibid. 15 (no. 1), 15 (1989). W. Hawley, P. Reiter, R. Copeland, C. Pumpuni, G. Craig, Science 236, 1114 (1987). W. Bradshaw and C. Holzapfel, Oecologia 57, 239 (1983); ibid. 74, 507 (1988); R. Copeland and G. Craig, Ann. Entmol. Soc. Am. 83, 1063 (1990). 6. W. Black, K. Rai, B. Turco, D. Arroyo, J. Med. Entomol. 26, 260 (1989); C. Ho, A. Ewert, L. Chew, ibid., p. 615. 7. Aedes albopictus and one A. triseriatus population were established by mosquitoes collected in New Orleans, LA. Additional A. triseriatus populations were established by females from central Massachusetts. A three-way analysis of variance of the interactions of Louisiana and Massachusetts A. triseriatus with A. albopictus reveal no statistically significant differences betweenA. triseriatus strains (T. Livdahl, unpublished data), and the results presented here combine the results of both strains. 8. After removing mosquito larvae, without removing detritus, fluid contents of ten treeholes and ten tires were pooled and homogenized with a canoe paddle during fluid disbursement. 9. T. Livdahl and G. Sugihara,J. Anim. Ecol. 53, 573 (1984). 10. Some cohorts failed to produce adult females. In such cases, the cohort was pooled with emergence data from another cohort within the same experimental cells, with r' calculation based on the total number of individuals for the pooled cohorts. 11. R. Sokal and F. Rohif, Biometry (Freeman, New York, 1981), pp. 795-799. 12. J. Hard, W. Bradshaw, D. Malarkey, Oikos 54, 137 (1989). 13. E. Walker and R. Merritt, Environ. Entomol. 17, 199 (1988). 14. E. Schreiber, C. Meek, M. Yates, J. Am. Mosq. Control 4, 9 (1988). 15. G. O'Meara, "The spread of Aedes albopictus and Aedes bahamensis in Florida," paper presented at the 1990 Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America, New Orleans, 2 to 6 December 1990. 16. J. Peterson, H. Chapman, 0. Willis, Mosq. News 29, 134 (1969). 17. We thank J. Edgerly-Rooks, S. Gaimari, and J. Turner for technical assistance, 0. Sholes, R. Bertin, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions, J. Freier for A. albopictus eggs, and NIH for financial support (R15AI27940 to T.P.L.). 21 January 1991; accepted 30 April 1990 bility, which allows them to serve as nucleation sites for proper folding oflarger RNAs (5). In this report we identify the structural properties that give rise to the sequence HANs A. HEUS* AND ARTHUR PARDIt requirements and high stability of hairpins containing GNRA loops. The GCAA and GAAA loops were chosen The most frequently occurring RNA hairpins in 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA contain a tetranucleotide loop that has a GNRA consensus sequence. The solution structures for these nuclear magnetic resonance of the GCAA and GAAA hairpins have been determined by nuclear magnetic (NMR) studies because they are the most resonance spectroscopy. Both loops contain an unusual G-A base pair between the first frequently occurring members of the GNRA and last residue in the loop, a hydrogen bond between a G base and a phosphate, family. The full sequences of the two hairextensive base stacking, and a hydrogen bond between a sugar 2'-end OH and a base. pins are shown in Fig. 1 (6). Proton and 31p These interactions explain the high stability of these hairpins and the sequence resonances were assigned by standard tworequirements for the variant and invariant nucleotides in the GNRA tetranucleotide dimensional (2-D) NMR techniques (7). Short (<4.5 A) 'H-'H distances were idenloop family. tified by 2-D nuclear Overhauser effect R NA HAmRPINs CONSISTING OF A either G or A) (1). The GNRA hairpin loops (NOE) spectroscopy, and Fig. 2 shows a double-stranded stem and a single- also occur with high frequency in catalytic, portion of the spectrum that was used to stranded loop are among the most phage, and eukaryotic signal-recognition assign aromatic and sugar C-i' proton resonances for the GCAA hairpin. Assignment common structural motifs in RNA. RNA particle (SRP) RNAs (2). The solution hairpin loops have been viewed simply as a structure of another frequently occurring RNA hairpin, which belongs to the UNCG means for the RNA strand to fold back on 9 G3t itself, and it was thought that the sequence family of tetranucleotide loops, has been G29 of the loop might not be very critical. How- reported (3). G5 1 RNA hairpins containing the GNRA ever, recent phylogenetic and thermody(1 .p Q namic studies have revealed strong size and loop sequence have been shown to be subU15 sequence dependencies for hairpin loops in stantially more stable, with melting transi0 E U121 C6 .p RNA (1). In particular, hairpins containing tion temperatures (Tm) more than 40C G9 CL higher than other less frequently occurring a tetranucleotide loop seem to be very imc Il, ci #C .c portant. Phylogenetic studies show that in sequences (4). These thermodynamic and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) tetranucleotide phylogenetic data led to the proposal that loops comprise more than 55% of all loops, GNRA tetranucleotide loops may be evoluand more than 50% of all tetranudeotide tionarily selected because of their high sta- 1W, F. A14..,5.8 .15.6 5.4 5.2 3.8 3.6 loops have the consensus sequence GNRA 6.0 en, (ppm) (where N can be any nucleotide and R is A A CA Structural Features That Give Rise to the Unusual Stability of RNA Hairpins Containing GNRA Loops 0 !GoS lo° 5G C-G 5G A C-G G-Cl 0 G-Cl 0 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309. *Present address: Department of Biophysical Chemistry, University of Nijmegen, Tournooiveld, 6525 ED Nij- megan, Netherlands. tTo whom correspondence should be addressed. 12 JULY 1991 G-C 1 G-U G-C 1 G-U Ppp A Pp UA OH UA OH Fig. 1. The full sequences for the GCAA and GAAA RNA hairpins (17). a .-. aDL Fig. 2. A portion of the 2-D NOE spectrum of the GCAA hairpin in D20 showing the aromatic H2/H8/H6 to sugar HI/H5 region. This spectrum was taken with -1.9 mM RNA hairpin in 100 mM NaCI, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pD = 6.8, at 25°C. Examples of sequential resonance assignment pathways involving H6/H8(n)- Hi'9(n)-H6/H8(n+1) resonances are illustrated. Note the unusual upfield shift of the G9 H-i'. REPORTS 191