‘Father Mac’ Miracle A

advertisement

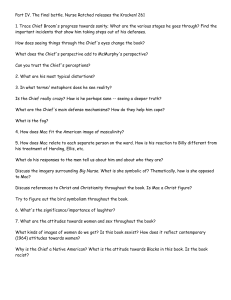

P H OTO C O U R T E S Y O F T H E R E G I O N O F P E E L A R C H I V E S , W I L L I A M P E R K I N S B U L L F O N D S 1 9 9 1 . 0 4 5 . K E N W E B E R ’ S H I S T O R I C ‘Father Mac’ the Miracle Man BY KEN WEB ER rchbishop John Walsh spent much of August 19, 1895, nervously peering out the window of his office on Bond Street in Toronto. The leader of Ontario’s largest Roman Catholic diocese was awaiting a telegram from St. Patrick’s in Wildfield where, just three days before, the parish had buried its beloved pastor, Father Francis McSpiritt. A sad event for the archbishop, losing a priest, and it meant he would now have to go through the delicate politics of choosing a new pastor for the parish. It was a different matter, however, that was making him anxious. He was well aware that “Father Mac”, as parishioners called him, had been extremely popular. Still, the number of mourners at the funeral had been mind-boggling. Not only did Gore Township turn out, and a good part of Albion and Adjala, there were large delegations from Brampton, Caledon East, Mono Road, Streetsville, even Dufferin County, a good many of whom he knew were stalwarts of the Orange Lodge. One group had come all the way from Kleinburg on foot. The passenger train from Niagara Falls had to put on an extra car! The archbishop had rarely seen such an outpouring of affection for a simple parish priest. But in truth, “simple parish priest” didn’t quite describe Father Mac. Francis McSpiritt was born in County Cavan, Ireland, in 1830, and came to Canada about 1855. He was ordained in Toronto ten years later and sent as curate to what many still called The Gore Mission: St. Patrick’s in Wildfield. A The position was a bit of a plum for a young priest, for St. Patrick’s was the second oldest parish in the archdiocese of Toronto. Almost immediately, though, he was sent farther west in Peel, to be pastor of St. Cornelius in Silver Creek, and then in 1869, was transferred to Niagara Falls. Here, in the premier tourist hot spot of North America, Father McSpiritt became known as a maker of miracle cures. Shortly after his arrival, word spread like wildfire through southern Ontario and New York State that this impatient, blunt but friendly priest had cured a Canadian girl of St. Vitus Dance (a form of chorea) and an American man of blindness. Archbishop Walsh’s predecessor, J.J. Lynch, had at first been unimpressed by this phenomenon, then embarrassed, and finally, angry. Lynch felt that one of his primary and most delicate tasks was to keep the Roman church safely and independently afloat in what was pretty much a Protestant – and Orange – sea in Ontario. It was enough that he had his hands full trying to suppress the Fenians, without having to deal with a priest whom people believed had a direct channel to God. The archbishop warned Father McSpiritt that charges of charlatanry could be brought against him, and begged that he give no more “thaumaturgic exhibitions.” But with the stubbornness that marked his character, the priest carried on, explaining that he was only a divine instrument, used by The Master to relieve human misery. “It is between the afflicted and God,” Father Mac always insisted, “I know nothing of it.” H I L L S The archbishop’s response was a time-honoured one. In 1875, he lifted Father Mac out of the high-profile Niagara posting and set him down in remote rural Ontario. St. James’ parish in Adjala Township had bad roads, no rail line and no large towns. Better yet, with the exception of pockets in Albion to the south, it was surrounded by a population that was solidly Protestant. But if the plan was to contain this bumptious Irish priest, it didn’t work. For the next 12 years, Father McSpiritt thrived at St. James’ and word of even more miracles flowed south to the chancery office in Toronto. A similar buzz continued from St. Patrick’s in Wildfield, after he had returned at his own request in 1887. In both parishes, even his Protestant neighbours were known to turn to him in times of stress – even though Father Mac emphatically pointed out that he didn’t think his powers would work on Protestants. Still, several supplicants allegedly were tossed out of their local Orange Lodge for crossing the line. Peel historian Perkins Bull has recorded more than a dozen of Father Mac’s miracles in considerable detail. A typical case involved the Bradley family of Palgrave, whose young son had epilepsy. As Protestants, the desperate family had turned to Father McSpiritt reluctantly. After spending a very short time with their child, Father Mac told the Bradleys they might see one more seizure but that would be all. As if on cue, the boy had an episode on the way home to Palgrave but never suffered one again. He died years later from diphtheria. An important feature of the priest’s reputation as a healer was his low-key style. Apparently, Father Mac never indulged in anything more dramatic than making the sign of the cross. Often, he would just tell the supplicant to go home and pray, and everything would be all right. However his instructions for giving thanks after a cure sometimes raised eyebrows. Two of his favourites were to tell women not to comb their hair on Fridays and to tell men to refrain from shaving on Sundays. On other occasions, the rigidly teetotalling priest revealed an extraordinary level of empathy by directing grateful pilgrims to limit themselves to only two drinks a day. Fortunately for those who sought his ministrations, after the move to Adjala, there were no more official warnings to stop. This somewhat uncharacteristic sensitivity on the part of the church hierarchy may have been because this humble priest sought nothing for himself. He ate sparingly; his cassock was shabby; his buggy rattled and fell apart regularly. Had it not been for an informal committee of parishioners who stoked his fires in winter and kept up his woodpile, he might have frozen to death. His only vanity was a monstrous stovepipe hat said to have come with him from Ireland. It is possible, too, that the hierarchy may have been slightly intimidated by the overwhelming response to Father McSpiritt. Pilgrims sought him out from across Ontario, from the northeastern U.S., and even from England, and built his reputation with tales of cure upon miraculous cure. Although epilepsy seems to have been somewhat of a specialty, belief in Father Mac’s powers covered all forms of affliction. Following a blessing by Father McSpiritt, for example, a woman from New York recovered from life-threatening gunshot wounds. In gratitude, she later built a grotto beside his grave at Wildfield. It was this depth of belief in the priest’s powers and the extent of his reputation that made Archbishop Walsh so uneasy that Father Mac’s funeral might kick off a wave of miracle mania. Thus, when the telegram finally arrived that August day, he was greatly relieved to learn that neither the Bolton Enterprise nor the Brampton Conservator had mentioned miracles in their respective obituaries. What did bring a frown to his face – and he read it twice to be sure – was the news that people were scooping handfuls of earth from the grave. Not quite mania, thankfully, but an indication that not even death could diminish belief in the miraculous powers of Father Mac. Although Archbishop Walsh wouldn’t know it, for he died only three years later, the practice of taking earth from Father McSpiritt’s grave at St. Patrick’s in Wildfield would continue for decades. Caledon writer Ken Weber is the author of several best-selling books. His most recent title is The Armchair Detective. Sainthood for ‘Father Mac’? Not likely. The modern day canonization process is tightly controlled by the Vatican and requirements of proof for the kind of cures attributed to Father McSpiritt are extremely rigorous. Although the sheer number of miraculous remissions credited to him forces the conclusion that there was indeed something most extraordinary about this priest, there is apparently no scientific documentation of the type that would pass the test. As well, it seems that no one in the archdiocese of Toronto has ever come forward to champion the cause, an essential requirement to get the Vatican’s attention in the first place. I N T H E H I L L S S P R I N G 20 01