The several elections of 1824. Abstract

advertisement

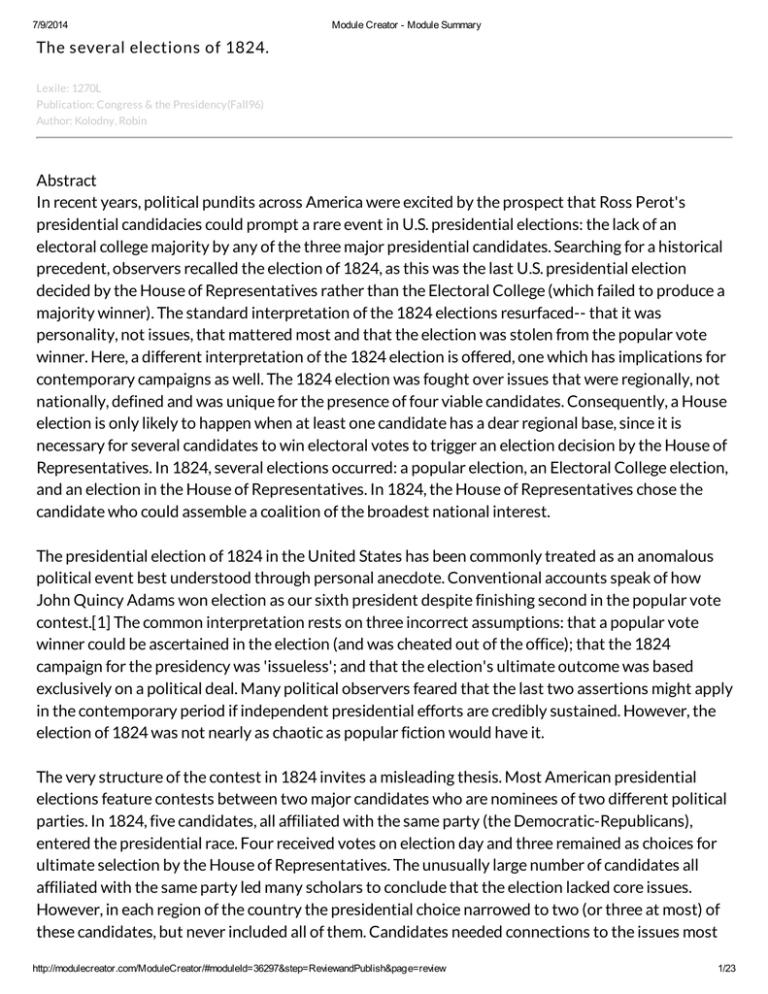

7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary The several elections of 1824. Lexile: 1270L Publication: Congress & the Presidency(Fall96) Author: Kolodny, Robin Abstract In recent years, political pundits across America were excited by the prospect that Ross Perot's presidential candidacies could prompt a rare event in U.S. presidential elections: the lack of an electoral college majority by any of the three major presidential candidates. Searching for a historical precedent, observers recalled the election of 1824, as this was the last U.S. presidential election decided by the House of Representatives rather than the Electoral College (which failed to produce a majority winner). The standard interpretation of the 1824 elections resurfaced-- that it was personality, not issues, that mattered most and that the election was stolen from the popular vote winner. Here, a different interpretation of the 1824 election is offered, one which has implications for contemporary campaigns as well. The 1824 election was fought over issues that were regionally, not nationally, defined and was unique for the presence of four viable candidates. Consequently, a House election is only likely to happen when at least one candidate has a dear regional base, since it is necessary for several candidates to win electoral votes to trigger an election decision by the House of Representatives. In 1824, several elections occurred: a popular election, an Electoral College election, and an election in the House of Representatives. In 1824, the House of Representatives chose the candidate who could assemble a coalition of the broadest national interest. The presidential election of 1824 in the United States has been commonly treated as an anomalous political event best understood through personal anecdote. Conventional accounts speak of how John Quincy Adams won election as our sixth president despite finishing second in the popular vote contest.[1] The common interpretation rests on three incorrect assumptions: that a popular vote winner could be ascertained in the election (and was cheated out of the office); that the 1824 campaign for the presidency was 'issueless'; and that the election's ultimate outcome was based exclusively on a political deal. Many political observers feared that the last two assertions might apply in the contemporary period if independent presidential efforts are credibly sustained. However, the election of 1824 was not nearly as chaotic as popular fiction would have it. The very structure of the contest in 1824 invites a misleading thesis. Most American presidential elections feature contests between two major candidates who are nominees of two different political parties. In 1824, five candidates, all affiliated with the same party (the Democratic-Republicans), entered the presidential race. Four received votes on election day and three remained as choices for ultimate selection by the House of Representatives. The unusually large number of candidates all affiliated with the same party led many scholars to conclude that the election lacked core issues. However, in each region of the country the presidential choice narrowed to two (or three at most) of these candidates, but never included all of them. Candidates needed connections to the issues most http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 1/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary salient in that region of the country, or their names did not appear on the ballot. Looking at who appeared on the ballots in the various states tells us much about the central political problem revealed by the election of 1824: the dissolution or disjunction[2] of revolutionary era politics as the next political generation began to take power. The election of 1824 provides a rare opportunity to see how the confluence of two major factors resulted in apparent disarray: sectionalism and the pre-alignment of the party system. Regional divisions cleaved along two central issue dimensions: the relative strength of nationalism (the power of the federal government vs. the power of state governments) and the nature of political participation (elitist or egalitarian republicanism). The various candidates competed in either one or both of these issue dimensions. One of these tensions usually was resolved in a particular region (for example, Westerners in both the North and South were overwhelmingly supportive of egalitarian republicanism, leaving the role of the national government as the central question). The incongruity of these contests -- resulting in several elections occurring simultaneously -- is not a reflection of the banality of politics in the 1820s, but of the consequences of political party breakdown. This intense localism was based on competing definitions of the United States as a nation. Regional tensions and sectional rivalries that would tear the nation apart in 1861 were already in existence at least by 181920 (the Missouri Compromise) and arguably as early as the Constitutional Convention (Stampp 1980).[3] As long as the federal government remained small and run by those who founded the country, the concept of union remained on the sidelines. But in 1824, none of the assumptions concerning the role of government or political leaders could be sustained. The events of 1824 also merged with a discussion of the appropriate method for selecting presidents and, indirectly, the role of the president in the political system. These issues were essential to the politics of the election of 1824 because they embodied not only political party incoherence, but an intersection of the issues at hand. Who would participate in presidential selection and what role the president and the political parties should play in the political system were highly salient. The presidential selection apparatus mattered in 1824 because it illustrated the changing role of political parties in America. The founders envisioned a 'party-less' polity and designed the presidential selection mechanism to retard any party development. When parties emerged anyway, they found the presidential selection system inappropriate for their needs. National politicians working in Washington (especially Congress) created a centralized party system and altered the manner of presidential selection. As the first party system gradually deteriorated, it left a vacuum in presidential selection practices. Whereas the founders envisioned a system in which state representatives (electors) voted for local or regional champions, Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans developed the norm of making a decision about presidential selection in Washington which would then be communicated to the various states' electors. As mass democracy approached and the Jeffersonian tradition of party waned, voters and politicians were adrift. The election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 ushered in a new era of presidential nomination and hence presidential selection that would make mass-based political parties a permanent part of our political system (McCormick 1982). http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 2/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary Delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 sought a presidential selection procedure that would both reflect the will of the people and preserve the sanctity of federalism. The compromise of a neutral state-selected slate of electors to elect presidents, rather than presidential selection by governors or state legislatures, became known as the original Electoral College. The electors would presumably be less liable to deception than the people at large. Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution specifies that the number of electors awarded to each state shall be equal to the number of senators and representatives assigned to that state, and that the electors themselves shall not be elected officials of the United States. The method of selection of individual electors was left to the discretion of the individual states. Each elector cast two votes, one each for two separate individuals, with the restriction that at least one of the candidates selected could not be a resident of the elector's home state. The candidate receiving the highest number of electoral votes would be elected president, provided he had a majority, and the candidate receiving the second highest would be elected vice president. If no candidate received a majority of electoral votes, the House of Representatives would select the president. The Senate would select the vice president. The five candidates with the highest number of votes would enter into an election by the House. A "House election" equalized the political power of all states, giving each state congressional delegation one vote. To win, a majority (50% + 1) of the states was required. This system was in effect for the first four presidential elections (1788, 1792, 1796, and 1800). Some founders feared this system would result in ties for the presidential contest, especially if two like-minded candidates ran. The infamous election of 1800 proved those fears were justified. In this election, the Democratic-Republicans, the first true opposition party in America, intended Thomas Jefferson to be their presidential candidate and Aaron Burr to be their Vice Presidential candidate. Since each Republican elector cast two votes (without specifying the intended office), Jefferson and Burr tied at 73 electoral votes each for the presidency. The House of Representatives had to choose between Jefferson and Burr for the presidential office. Thirty-six separate ballots were cast before Jefferson emerged the winner. The events of this election led directly to the drafting and subsequent ratification of the 12th amendment to the Constitution, adopted September 25,1804.4 This amendment directed electors to indicate their choice for President and Vice President separately, making two distinct races. This change was a tacit acknowledgement that earlier hopes of internal counter-balancing in the executive branch (based on the idea that no political parties would develop and hence no 'tickets' would form) were forever gone. The presidential and vice presidential candidates would now be linked. The amendment also changed from five to three the number of candidates allowed to enter the House election if no candidate received a majority of electoral votes. The 12th amendment did not change the rules about the selection of individual electors to serve in the Electoral College. The states retained (and still control) this power. Three methods for the selection of electors in the states emerged by 1788: 1) appointment by the legislature; 2) popular vote by a general ticket; and 3) a `mixed' or district system. The first method, state legislative appointment, did not involve the voting public except in their indirect selection of the legislature. The second http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 3/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary method, the general ticket, required a centralized body (normally a caucus) of each party or faction to compose a slate of electors. Voters would then choose between competing slates and the entire number of electors would be awarded to the winning slate at large (the winner-take-all method). The third method, the district system, required an initial popular vote in variously delineated districts of the state and electors were then apportioned accordingly.[5] Most states chose legislative appointment of electors initially. Over time, selection of electors by general ticket was seen as more democratic. As new states entered the union, they tended to adopt the general ticket method outright. The general ticket was preferred to the district system because a state's political impact on the election increased when electors were allocated as a slate instead of divided among districts. These considerations pressured some states to revise their laws on elector selection (Zagarri 1987). However, by 1824, only 13 of the 24 states were selecting electors by general ticket. Five states used the district system, and six still used legislative selection. Table 1 lists the states by their method of elector selection. The 'will' of the people in the six states using legislative selection, accounting for 71 of the 261 electoral votes in 1824, cannot reliably be discovered.[6] Further, even where there was popular election of electors, voter turnout was lower than in previous statewide elections. Thus, the idea that the mass of the people spoke and were ignored is suspect (McCormick 1960). This is an important element in the argument against the stolen election thesis. One consequence of the election of 1824 was the abandonment of legislative selection of electors. By 1828, only two states, Delaware and South Carolina, used legislative selection. From 1832 to 1860, only South Carolina chose the legislative method. The discussion of who would select electors accompanied a discussion of who would name the national parties' choices for the electors' consideration. Andrew Jackson would use the events of 1824 to transform the manner of nominating presidential candidates from the congressional nominating caucus to the party nominating convention (McCormick 1982). Nominating caucuses had been an integral part of electoral politics in this country virtually since its founding, but by 1824 they were waning. The first nominating caucuses of a partisan nature were not at the national level, but held within the states for nominating state candidates. Giving state legislatures the responsibility of making nominations began as a matter of convenience. Communication and travel difficulties prevented local representatives from congregating to reconcile their respective decisions. It seemed logical to leave nominations to "...men enjoying the confidence of the voters of the state [who] were already assembled in the capital in pursuance of their functions of members of the legislature" (Ostrogorski 1900, 257). By 1796, nominating caucuses in state legislatures became standard practice for nominations of Governor and Lt. Governor in all the states and thus insured permanent party organization. These caucuses also generally assumed the responsibility for the nomination or appointment of presidential electors. Later, a congressional caucus decided upon a presidential nominee to represent the party. By making a formal recommendation, the caucus was denying the elector his central role as intended by the framers (Ostrogorski 1900). Electors began to follow the lead of the congressional caucus rather than make their own independent decisions. In 1824, William Crawford was the choice of Jefferson, http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 4/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary and his continued allegiance to Jeffersonian ideals stood in stark contrast to what would become Jacksonian ideals. A consequence of this affiliation was that Crawford became the choice of the congressional caucus, an albatross that would prevent his serious consideration in most areas of the country outside the South.7 Although 216 congressmen were eligible to participate in the caucus, only 66 attended. They were principally from the states of New York, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia (Stanwood 1884; Hargreaves 1985). Dissatisfaction with the congressional caucus resulted in its abandonment by the Federalists in 1816 and by the Republicans after 1824. Starting in 1832, nominations were made by the mass public instead of elites. The 'corruption' implied by the congressional caucus system of presidential selection became an important issue itself in the 1824 campaign (Remini 1981, 80). The results of the general election of 1824 reveal what the congressional caucus had managed to hide: the extreme sectional nature of the country. With the nation's fiftieth birthday fast approaching, the search for a common American identity intensified. The revolutionary generation had passed on, leaving the destiny of the new nation in the hands of the next generation. Because of the loose ties this new generation had to the founding and because of the multiplicity of experiences that had shaped the nation, no one had dear authority to guide the country's future, and the party system that existed did not have the capacity to articulate the new dimensions of debate. It was, as Gordon Wood explains, an extremely unsettling time for American society, with no clear lines of authority (Wood 1988). A country of 13 states that fought a war for a collective goal became a loosely affiliated `union' of 24 states with vastly different histories and in varying stages of political and economic development. Consequently, there was no universal vision of where the country ought to go and this culminated in local debates of the national interest. The cleavages were several: North versus South, East versus West, frontier versus seaboard, industrial versus agrarian. Such cleavages encouraged a debate between pursuit of a common national interest and the preservation of state autonomy. Regional affinities were intense in this debate and a further line of fissure developed between the traditional elitist republicans and the emerging egalitarian republicans. The competing notions of republicanism (meaning the nature of representation in the American democracy) are critical. Lawrence Kohl's analysis of the differences in Democratic and Whig party mentalities (which crystallized out of this 1824 struggle) shows their world outlooks. Each side viewed individualism differently. For the traditional or 'elitist' republicans (the future Whigs), equality meant equality of opportunity and success required self-discipline as well as compromise and sacrifice for the collective good. Consequently, government should strive to level the playing field for individuals using policies which would minimize the differences of the regions. Such actions would require "wise men of broad vision" in government (Kohl 1989, 90-1). The egalitarian republicans (future Jacksonian Democrats) deeply mistrusted the creation of new, centralized institutions such as banks, corporations, and bureaucratized governments because they were seen as deliberately creating inequalities among men. The less ordinary people controlled things, the more egalitarians mistrusted them. Egalitarian republicans valued universal suffrage and local rather than national, control of government (Koh11989, 27-33; 58-9). http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 5/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary As just described, the two major axes, nationalism and republicanism would emerge in the second party system. The type of republicanism, or more precisely who should rule, was a matter of central importance. The Federalist party had always championed elitist republicanism, but once Federalists disappeared from the national political arena, the Republican party more obviously displayed this tension. The older regions of the country, specifically the eastern seaboard, tended to be most comfortable with the elitist republican ideas of the founders. The newer parts of the country, all the frontier areas, had no established hierarchical political culture and based their new state governments on egalitariardsm. This division manifested itself partly in a disagreement over the nature of the party and electoral system. The elitist republicans were content with the idea of a congressional nominating caucus, or some other form of party caucus, determining presidential candidates and issues. The egalitarians insisted on openness and popular will. The other major issue dimension in 1824 was the appropriate role of the national government in the economic development of the nation. An economic package known as the `American System' provoked a variety of regional disagreements. The American System, named and championed by Henry Clay, advocated a protective tariff, internal improvements, and a national bank. The policy was meant to remove major hindrances to economic development for domestic industries (Baxter 1995). The economic sanctions against Great Britain preceding and during the War of 1812 greatly stimulated manufacturing and grain-producing areas, found mostly in the North and West. Once the war concluded and European imports returned to American markets, manufacturing and grainproducing industries found that their goods were no longer price competitive in domestic or foreign markets. The northern and western states argued for a protective tariff that would preserve their industrial economies by artificially sustaining the wartime price levels. The northern and western regions declared tariffs in the national interest even though these taxes would injure the Southern economies which had no local industries to protect (Remini 1991, 228-233). Southerners also had no interest in paying higher prices for domestic goods, especially if the goal was to strengthen northern industry. Another major part of the American System controversy involved internal improvements. The Westerners in both the North and South needed good roads and canals to communicate and conduct their business with other parts of the country and abroad. Transportation difficulties encountered during the War of 1812 highlighted these problems. As troops and supplies had to be moved further west, the poor state of the roads became apparent (Taylor 1964). However, the East was reluctant to finance the construction of the western states' infrastructures and tried to portray internal improvements as a state matter. Clay, hoping to build a national coalition, linked the two issues as Samuel Francis explains: The crux of the American System argument was that the vision for America should be based on a view of a strong national government rather than a weak national government with strong, autonomous state governments. Northern and western regions, interested in creating a genuine national http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 6/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary infrastructure to promote commercial development, allied for strong nationalism while the South opposed it, finding discussions of infrastructure contrary to their states' rights views. This nationalism-states' rights tension was the basis of the slavery question as well. The Missouri Compromise of 1819 had not resolved concerns about the future of slavery in the nation. Northerners and northwesterners came to resent the three-fifths compromise in the Constitution which they felt allowed the South to be unfairly over represented. As the country expanded westward, these northern and southern cleavages on the slavery question endured. In the North and Southeast, slavery was understood as an economic and representation (of property, not of persons) issue. The relative absence of slave labor in the newer western areas tended to foster less tolerance for the existence of slavery. The northern and southern Westerners had economic concerns as well regarding slavery, but they were rooted more in issues of egalitarianism and the elite society of the slaveholders (Freehling 1990). Eugene Roseboom captures the link between the issues and candidates in his overall evaluation of the 1824 campaign: The individual personalities of the candidates were certainly factors, but they were secondary to the relevance of the issues they represented in various regions. Discussion about candidates largely existed in the regions where their presence would have ties to the local contest, and where they were not redundant. Figure 1 illustrates this point. In most of the regions of the country, debate centered on only one of the two issue dimensions. Therefore, it would be meaningless to field all four candidates in every area. Two would normally be sufficient to address the relevant debate. The following sections on the candidates and regional contests illustrate this point. Five individuals were major candidates in the election of 1824: John C. Calhoun, William Crawford, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. Calhoun, a former congressman from South Carolina and incumbent Secretary of War, was the first candidate to enter and to leave the race. One major reason for Calhoun's entrance into the race was his repugnance at the idea of William Crawford's designation as Jefferson's heir. Calhoun thought him an elitist and worse, a potential ally of old style Federalists? In contrast to Crawford, Calhoun's politics were strongly nationalist and emerging egalitarian at that time. He was popular in Pennsylvania where his family originally settled (Hargreaves 1985) and in his home state of South Carolina. Calhoun thought he might be able to capitalize on anti-Crawford sentiment, but when it became clear that Andrew Jackson would assume that role, Calhoun called an end to his effort and instead declared his interest in the Vice Presidency. He was elected Vice President easily in 1824. Of all the candidates in the election, William H. Crawford was the one whose status was most volatile. Crawford was the clear front-runner in the election's early stages until September of 1823 when he suffered a debilitating stroke. Even in illness, Crawford retained significant support until the last stages of the election. Crawford was a U.S. Senator, and then Secretary of the Treasury throughout http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 7/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary the Monroe administration. Though a Georgian, Crawford was considered the logical heir to the Virginia dynasty, since he was a protege of Jefferson. Crawford's nomination by the congressional caucus confirmed his status as heir. This designation would harm him considerably throughout the race. Andrew Jackson was the most popular military hero of the first half of the nineteenth century. His fame, especially from the Battle of New Orleans, was the force behind his entrance into the presidential arena. Jackson was a well-known political enemy of Crawford and Clay who both criticized him for his treatment of Indian matters in Florida, though both Adams and Calhoun supported him (Sellers 1957; Hargreaves 1985). The Tennessee legislature nominated Jackson for the presidency in 1822, though they also sent Jackson to the Senate in 1823 for lack of a sufficiently strong anti-Crawford candidate? While in the Senate, Jackson's activities remained low profile, but the prospect of his presidential candidacy did not. John Quincy Adams, son of John Adams, second president of the United States and a founding father, enjoyed an early career of foreign diplomacy. Though he served in the U.S. Senate as a moderate Federalist, he left the Federalist party in 1809 because of the party's support of Great Britain in the trade embargo. He supported Jefferson's embargo and alienated the Massachusetts state legislature and New England Federalists generally who labeled him `apostate.'[10] However, this also gave John Quincy Adams the legitimacy to serve in subsequent Republican administrations. During the Madison administration Adams served as minister to Russia and later helped negotiate the Treaty of Ghent. In 1817, Adams became Secretary of State in President Monroe's cabinet, where he authored the Monroe doctrine. Henry Clay started his national political career in the U.S. Senate and then was elected to the House of Representatives in 1811. Clay became Speaker of the House immediately and raised the status of both himself and the post by his activist role. Clay considered his position as Speaker to be political, not exclusively parliamentary. He obtained the enactment of legislation on the protective tariff, internal improvements, and the Missouri Compromise despite the vetoes of Presidents Madison and Monroe. Mary Follett claims that "Clay was the most powerful man in the nation from 1811 to 1825" (Follett 1896, 79). Such power, substantial as it was, did not satisfy Clay's ambition and he thirsted for the presidency. Though Clay knew he did not have a national reputation, Robert Remini believes that Clay deliberately devised a regional strategy for a campaign to get him into the House election. Clay thought this was possible because of the political vacuum that formed after the death of 'King Caucus' (Remini 1991, 249). Once it was clear that the congressional caucus would meet and nominate Crawford, the first party system collapsed. If we believe Skowronek's account of events, Monroe deliberately did not indicate a successor and therefore set events in motion (Skowronek 1993, 90-92). However, Thomas Jefferson made it perfectly clear that he saw Crawford as the only true and proper heir of the Virginia dynasty. From 1822 on, the discussion about presidential selection, republicanism, and nationalism consumed http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 8/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary the country and led each of the above named individuals to believe he had a fair shot at the presidency. The expectation from the outset was that with so many candidates in the race, no one was likely to emerge as a majority winner. With no party apparatus to arbitrate the contestants, each candidate's strategy became to either eliminate one of the other candidates or to make it to an election in the House of Representatives. The election of 1824 had three components: the popular election, the Electoral College vote, and the House election. Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3 show the results of the popular and electoral votes. In terms of the popular election, no 'national' election occurred in 1824 in the sense that we usually understand the term. Rather, a series of regional elections occurred, each trying to define the national interests in their terms? In almost no state did all four presidential contenders receive support. In most states where more than two candidates competed, at least one candidate received a negligible share of support. The general election returns suggest distinctly different contests in the following regions: New England, the new Northwest, the South, and the MidAtlantic area. The issues and regions correspond to the cleavages shown in Figure 1. New England (Table 3) New England's dominant candidate was never in doubt: Adams ended up with 84% of the popular vote and all 51 electoral votes from this region. Although John Quincy Adams had left the Federalist party, he was still an Adams and was therefore considered the closest thing to a regional representative. In all of New England, the republicanism axis was settled: egalitarian republicanism did not have an audience here. There was some discussion of the nationalist dimension, though strong nationalism was favored. Ironically, Adams previously rejected the Federalist party because of their regional, rather than national, outlook. Still, Adams was not entirely comfortable being a Republican because he thought the Republicans were generally hostile to an 'aristocracy of virtue' and sometimes bordered on mobocracy (Thompson 1991). Federalists could accept Adams because they did not see him as an extreme Republican. Crawford's name, although linked with the opposition to Adams, never could attract enough support to have a reasonable chance of success. He was Adams's only opponent. The two Western candidates were never mentioned in the contest in this area. New Englanders, who had considered secession, were suspicious of the other regions: Westerners for their egalitarian reforms and Southerners because of their use of the slavepower (especially for representation) and their domination of the presidency for the past quarter century. Also, since New Englanders accepted the idea of elitist republicanism, there was no audience for Clay and Jackson. The modest vote for Crawford (less than 14% in the region) had its roots in opposition to the American System. The vote for John Quincy Adams indicated a victory of strong nationalism and elitist republicanism. The South (Table 4) The contests in the eastern South (Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia) and western http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 9/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary South (Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana) were slightly different due to the salience of the slavery issue in these regions. The overwhelming majority of slaveholders were located in the eastern South at this time. A common element in the election in the South as a whole is the absence of Henry Clay as a candidate. As a strong nationalist with weak pro-slavery views, his position was least preferable to all parties. In the eastern south, the contest was between William Crawford and Andrew Jackson, who differed in their conceptions of republicanism, but were both states' rights champions. No candidate with a hint of anti-slavery views, namely Adams and Clay, gained serious support in these states. Jackson and Crawford remained as the two viable candidates but Crawford had the most extensive political ties here. He won the popular vote contest in Virginia handily and came in a respectable second to Jackson in the popular vote in North Carolina.[12] Georgia and South Carolina had legislative selection of electors. In the electoral vote count, Crawford won all of Georgia's and Virginia's votes; Jackson won all of South Carolina's and North Carolina's votes. Crawford and Jackson both had pro-slavery and state's rights' views, but Crawford was considered the meritorious insider representing the establishment view of republicanism that stood in stark contrast to Andrew Jackson's egalitarian views and following. The western South was different. In Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, the contest was between Adams and Jackson. These areas were divided over the extent of nationalism and the presence of slavery. The newer western portions of these states were in favor of a national system of internal improvements while the eastern sections with significantly better transportation systems, were opposed to this perceived intrusion of the new national government on state powers. However, this east-west split was the geographical division concerning internal improvements that existed throughout the country, not exclusively in the South. Adams' anti-slavery and pronational views earned him support here. Anti-Crawford sentiment in this region was strong. In Alabama, the victory of Andrew Jackson (in excess of 70% of the popular vote) demonstrated a sound repudiation of the Georgia faction (Thomton 1978). The cases of Mississippi and Louisiana are not quite so clear: Mississippi because of its youth as a political entity and small population, Louisiana because of the control that the state legislature had over the election there. The Mid-Atlantic States (Table 5) The major issues in this area were criticism of the current electoral laws and support for protective tariffs. These states contained the older, financially established ports--New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore. Because of the post-War of 1812 economy and the tariff, industries grew in these areas and with them a working class. This class, energized by ideals of western democracy, aided in the promotion of electoral reform and extension of the franchise. The tension was between strong economic nationalism in former Federalist strongholds and strong egalitarianism. Adams and Jackson were the major contenders. http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 10/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary In Pennsylvania, the method of electing the president was a central issue in the 1824 campaign. Crawford, Calhoun, and Jackson received many nominations in county and city conventions throughout the state, and the Harrisburg Convention for the statewide party was held on February 11, 1824. They nominated Jackson, stressing his freedom from any entanglements with "King Caucus" (Hailperin 1926). The reasons for Pennsylvanians' support for Jackson were many: his military record, his opposition to federalism, his Scotch-Irish heritage, his dissociation with the national cabinet (due to its long consideration as presidential incubator), and his ambiguity on the American System. As in Pennsylvania, the major political concern in the state of New York was the method of election of the president. However, the arenas in which this common conflict played out were vastly different. In Pennsylvania it was found in the various popular conventions; in New York it was in the backrooms of the Albany Regency and the floor of the New York state legislature. The dictation of the congressional caucus was the issue that remained supreme (Rammelkamp 1905). But in the meantime, the debate over reform in the electoral laws - led by Martin Van Buren and the Albany Regency on the side of strong party control and DeWitt Clinton and the anti-Regency faction for the cause of popular control - became inextricably linked with the electoral fates of Crawford, Adams and Clay in the state. At question was the selection of electors by the state legislature, rather than by the people. The Crawford supporters (mostly members of the Regency) succeeded in having a vote on electoral law reform postponed so that the state legislature would decide on the electors for the presidential election of 1824, insuring that a general ticket method of elector selection would not be in place until 1828. What they did not consider was the public outcry over this postponement, resulting in many victories for anti-Regency candidates for governor and the state legislature. This sent a significant signal to the state legislature about to choose presidential electors. A complex series of internal political manueverings followed and Adams received 26 of the state's 36 electoral votes. In Maryland, these issues seemed muted due to the still strong presence of the Federalist party. Maryland enjoyed healthy two party competition until 1821. Indeed, the Federalists controlled both houses of the Maryland state legislature in 1816 and the Senate was still Federalist in 1819. As the more urban areas of the state thrived, the Republican party gained in electoral strength and eventually controlled both houses by 1821. With the Federalists gone, the Republican organization began to disintegrate, its supporters finding the system of caucus nomination beyond utility - capable only of further division. This resentment, plus the interest in the tariff and internal improvements, explains why Crawford found no serious support here. It was Adams who benefitted from the old Federalist supporters, while Jackson received Republican support. Maryland's electoral votes were divided: seven for Jackson, three for Adams, and one for Crawford. Mark Hailer explains: "Despite Jackson's margin in electoral votes, he and Adams polled nearly the same number of votes. Jackson carried the old Republican districts of Baltimore and the western counties. Adams carried the old Federalist strongholds in southern Maryland and the Eastern shore" (1962, 313). Both sections of the state were united in their support of a canal and a railroad, to provide the western section of the state with better access and to promote the port of Baltimore. In the wake of the Federalists' demise, old Federalists saw the party's failure as a function of the role of parties themselves. They supported http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 11/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary Adams on the merits of his record and ran for their own offices as independents (Haller 1962). In Delaware, the Federalists were still viable as a state party. Therefore, the Democratic-Republican party was more united, backing Crawford as the party caucus's choice. The Federalists chose to back Adams because he was a committed nationalist. The state legislature selected two Crawford electors and one Adams elector for the Electoral College. In the House election, Delaware's only representative went for Crawford (Wire 1973). In New Jersey, Jackson would defeat Adams, winning all eight electoral votes. The Northwest (Table 6) In the wake of the Missouri Compromise, slavery positions were considered important to the campaign in the free northwest. However, in the four years since this event, no other high visibility slavery issue had arisen. This calm explains how Andrew Jackson garnered support in the Northwest although the slavery issue would certainly have hurt Jackson's chances (because of his pro-slavery views) there far more than Clay's. Henry Clay was keenly aware of this political reality. In a letter to Francis Brooke in February of 1824, Clay writes: "As I have told you before the northwestern states will go for Mr. Adams, if they cannot get me. They will vote for no man residing in a slave state but me, and they vote for me because of other and chiefly local considerations, outweighing the slave objections. On that you may depend" (Clay 1963:3,655-6). The tension in the Northwest was between strong egalitarianism and strong nationalism. Of course, the American System was of overriding importance to this area. This economic plan was important because the tariff would price domestically produced goods competitively with foreign imported goods, compensating for the increased transportation and start-up costs of domestic industry compared with those of the more established foreign (mostly British) producers. This in turn would "relieve the unprofitableness of agriculture, diversify industries, open new channels for capital and labor"(Roseboom 1917:164) and in this way enhance the autonomous political development of the whole country. Internal improvements would greatly lessen the costs of transportation and provide reasonable access for the West to eastern markets. The northwestern section could not support any candidate who did not advocate an economic plan favorable to domestic industry. Roseboom explains why Crawford found no support in the area: "The fact that he was most strongly supported in the Southern states where tariff and internal improvements were most unpopular was alone enough to condemn him....The fact that he was from a slave state and the supposed intrigues in which he was engaged for the presidency were further counts against him" (Roseboom 1917:166-7). These sentiments also help explain the support that Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams found for their campaigns. They also explain the `soft' support for Andrew Jackson. Jackson's personal popularity and advocacy of western democracy brought him some followers, but this could not make up for the fact that his stand on the American System was ambiguous. Most of the tenets of the western democratic ideal had already been realized here - there were no battles fought over electoral reform as in other parts of the country. This resulted in uneven support for Andrew Jackson. http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 12/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary Historical geography helps explain the popular vote in Ohio. Jackson's support was in the southwest near industrial Cincinnati and in the eastern part of the state which had been settled by many Pennsylvanians. Similarly, support for Adams came from areas settled by New Englanders. The rest of the state supported Clay. Donald Ratcliffe states more firmly that Adams would have received far more support in Ohio had he been perceived as more dedicated to the American System. That combined with his anti-slavery views would have made him unbeatable in the popular election. However, Ratcliffe says of the House election "...almost all Clay's adherents followed their favorite into an alliance with the Adams forces in 1825. This was a natural combination since, after all, they would almost certainly have united in 1824 behind a known northern supporter of the `American System' had one existed with a prospect of national success" (Ratcliffe 1973, 864). Illinois and Indiana gave strong support to Jackson, Adams, and Clay, reflecting tensions between views on slavery and egalitarianism. Since no candidate had gained a majority of the electoral votes, the election went to the House. As shown in Table 1, Andrew Jackson received the greatest number of electoral votes at 99, followed by John Quincy Adams with 84, William Crawford with 41 and Henry Clay with 37. Jackson's 99 votes fell short of the required majority of 131. The House of Representatives, according to the 12th amendment, decides the presidential election if no candidate receives a majority from the top three electoral vote recipients. Therefore Jackson, Adams, and Crawford became the candidates for the next phase of the election, excluding Henry Clay. This made for a very interesting struggle, quite distinct from that involving the popular and electoral vote. The three measures of the vote in 1824 (popular, electoral, and House) were extracted from three different audiences. The popular and electoral votes are inherently linked, although not entirely interdependent, but the votes of the congressional delegations in the House were much less dependent on the first two measures. Representatives were (and are) constitutionally forbidden from becoming electors because the Founders feared self-interest would prevent them from choosing wisely. Only in the rare circumstance where the Electoral College could not grant a majority to any candidate was the House to become involved in the process. It is important, also, to note the difference between independent electors casting their separate votes and state congressional delegations (of sizes varying from one to 36) casting a single vote amongst themselves. In 1824, there were 24 states in the union. To win the election in the House (as specified by the 12th amendment), a candidate needed to receive the votes of 50% of the states plus one (13 in 1824). John Quincy Adams received the support of exactly that many states on February 9, 1825 in the House election. Jackson received the vote of 7; Crawford of 4. (See Figure 4) Of the thirteen states Adams carried, seven were already "his" from the electoral college (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York). He gained the support of six more to win the election. Three of these (Maryland, Louisiana, Illinois) split their electoral votes previously and had given some electoral votes to Adams. The remaining three states (Kentucky, Missouri, and Ohio) http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 13/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary were solid supporters of Henry Clay. How Adams came to receive the votes of these last six states is of paramount interest. Clay's Role in the House Election Henry Clay was strategically placed. He was not only the excluded candidate; he was Speaker of the House as well. Clay wrote: "I only wish that I could have been spared such a painful duty as that will be of deciding between the persons who are presented to the choice of the H. of R" (Clay 1963:3, 8923). Many historians believe that Clay's influence was so great that if he had been one of the top three candidates to go to the House election, he would surely have won (Eaton 1957). Clay also believed this: "If the election comes to the H.of R. my election I think certain, if I should be one of the three highest" (Clay 1963:3, 645). Whoever Clay chose to support would undoubtedly have a great advantage. Of the three contenders--Adams, Jackson and Crawford--Clay opted to support Adams almost from the beginning.[13] Clay felt that Adams had the electoral momentum as early as June of 1824 when Clay's own prospects were still uncertain: "If I were to say whose prospects appear to me to be best at this moment, I should designate Mr. Adams" (Clay 1963:3,781).Based on the qualities of the three men presented to the House, Clay felt that Adams was his only reasonable choice. Clay had two objections to Crawford: his supporters and his health. The idea of "King Caucus" was anathema to Clay. He could not support that body's candidate. Indeed, Clay, Adams, and Jackson held this view in common: their mutual enemy was the caucus and its candidate, Crawford. As early as May of 1824, Clay had dismissed Crawford as a credible candidate: "The state of Mr. Crawford's health is such as to scarcely leave a hope of his recovery. It is said that he has sustained a paralytic stroke. His friends begin to own that his death is now but too probable, and that in any event he can no longer be held up for the Presidency" (Clay 1963:3,767). Clay had even more negative feelings toward Andrew Jackson. He had fought for Jackson's censure in the House after Jackson's activities in Florida. Clay wrote of Jackson: "As a friend of liberty, & to the permanence of our institutions, I cannot consent, in this early stage of their existence, by contributing to the election of a military chieftain, to give the strongest guaranty [sic] that this republic will march in the fatal road which has conducted every other republic to ruin" (Clay 1963:4,45-6). Aside from Jackson's personal offenses, Clay had political problems in supporting Jackson, since there would be little point to Clay supporting his rival in the West. Clay saw himself as the West's legitimate spokesman. To advocate Jackson's election would jeopardize his own political ambitions. Clay's statement on Adams speaks volumes: "Mr. Adams, you know well, I should never have selected if at liberty to draw from the whole mass of our citizens for a President. But there is no danger in his elevation now or in time to come" (clay 1963:4,47). That is precisely why Clay chose Adams: he was safe for the country and for Clay politically. Clay and Adams held similar views on a variety of issues. Adams had displayed sympathy for the American System, especially internal improvements. By http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 14/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary supporting New England's candidate, Clay could gain a foundation for power in the North. He would then be better placed for the presidency in the next election. Clay and Adams also shared similar views of foreign policy. A final consideration was that of Adams' disposition and background. To Clay, Adams' manner was better suited to leadership than Jackson's. Gerald Johnson describes Clay's sentiment: "From the beginning the American republic had been run by gentlemen...then for Clay to employ his influence to bring Jackson into office over a gentleman of the old school; a man familiar to Washington, a man who, whatever his objectionable idiosyncrasies, undeniably was a member of the ruling class, would have been sort of an abdication" (Johnson 1939:181). Clay saw himself as part of this tradition and his desire to uphold it prevailed. Adams and the "Corrupt Bargain" John Quincy Adams wanted very much to be president although, as mentioned earlier, he did not actively campaign for it. He had done what was necessary and proper to earn the office, he thought, and was now ready to reap the reward. Adams realized that his election in the House would be difficult. His support in New England was certain, but he would have to find support in other regions if he hoped to win. Clay gave his support to Adams unconditionally, but this support did not necessarily convey to Clay's supporters in Washington. They repeatedly appealed to Adams for a guarantee that Clay would be well-placed in an Adams administration. Adams, not wanting to be in the debt of any man, gave vague assurances: "with regard to the formation of an Administration...if I should be elected by the suffrages of the West I should naturally look to the West for much of the support that I should need" (Adams 1875:6,474). This was enough to satisfy many westerners, especially those from the Northwest and assured their support for Adams. Henry Clay was clearly cabinet material in his own right, whatever his position of influence in the House. As a superior statesman and clear regional representative, Clay would have been an asset to any administration's cabinet. Adams realized this and thus offered Clay the position of Secretary of State in his administration. In his Memoirs, Adams justified his decision to President Monroe: "I then said that I should offer the Department of State to Mr. Clay, considering it due to his talents and services, to the Western section of the Union, whence he comes, and to the confidence in me manifested by their delegations"(Adams 1875:6,508). Adams seems justified in discharging this public debt. At question is Clay's decision to accept the post. Clay's Acceptance of Secretary of State Clay first expressed repugnance, then reluctance, and finally acquiescence to accepting the cabinet post. In a letter dated December 22, 1824 concerning the impending presidential decision in the House of Representatives, Clay declared: "I would not cross Pennsylvania Avenue to be in any office under any administration which lies before us" (Clay 1963:3,900). However, in a letter dated February 4, 1825 (five days before the House of Representatives decided the election of 1824) Clay had a change of heart: "Most certainly, if an office should be offered to me under the new administration, http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 15/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary and I should be induced to think that I ought to accept it, I shall not be deterred from accepting it..." (Clay 1963:4,55-6). How did such a change of heart take place? Clay insisted that he would defer the decision to the wishes of his supporters, but submitted "that I had perhaps remained long enough in the H. of R.; and that my own section would not be dissatisfied with seeing me placed where, if ! should prove myself possessed of the requisite attainments, my services might have a more extended usefulness" (Clay 1963:4,73). As anticipated, Clay's friends concurred. Francis Blair wrote to Clay: "Your friends here all concur in the wish to see you Secretary of State, & ! have no doubt but the great mass of those throughout the State who preferred Jackson next to yourself will feel that they & the country have more than an equivalent for the loss of the house, on the part of the Western Candidate" (Clay 1963:4,91). Clay's acceptance brought cries of "bargain & corruption" - the idea that Clay gave Adams the election in return for Secretary of State. Historians disagree about whether such a bargain was struck. Andrew Jackson and his supporters, especially James Buchanan, actively spread the charge. The Jacksonians charged that Clay and Adams conspired to 'steal' the election from Jackson, arguing that Jackson was the popular vote winner[14] and thus deserved Clay's support in the spirit of preserving democracy. Jackson's argument for the existence of a bargain between Clay and Adams is based largely on third hand information and is also somewhat post facto (Stenberg 1934). Evidence suggests that if there was a bargain, it was implied, not explicit. However, the guilt or innocence of the parties involved has not been nor will probably ever be definitively established. Indeed, a tremendous historiography exists on the subject.[15] Amore plausible explanation is that Clay exercised bad judgement in accepting the position that was honestly offered, rather than Clay merely accepting his end of a corrupt bargain. The corruption charge stuck largely because the position of Secretary of State still carried with it the implied right of succession in the minds of some (at least it was certainly understood as a promotion from the Speakership) and because of Jackson's unrelenting efforts to make the charge stick so that his chances of achieving the presidency in 1828 would be enhanced. Whatever the validity of the 'bargain and corruption' charge, it is hard to imagine any of the three remaining candidates besides John Quincy Adams emerging victorious. Adams logically got the House vote of all six New England states (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island). It is also logical that he would win New York and Maryland whose states split their electoral votes, but whose congressional delegations clearly favored Adams. In Ohio and Illinois, the vote had been split three ways (Adams, Clay and Jackson) with Jackson winning a plurality. With Clay out of the race, Adams logically inherited his support, thus defeating Jackson. Both Kentucky and Missouri gave their overwhelming support to Clay, who in signaling his support of Adams, delivered these states (though it is doubtful they would have supported Jackson). These 12 states compose a strong nationalist coalition of northern and western states. The one state in Adams' coalition that does not make sense is Louisiana. Its electoral vote was split in Jackson's favor, but only slightly. Perhaps this is further evidence of Clay's influence. Jackson carried six southern and border states (Tennessee, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina) into the House vote. He should have had North Carolina also, but as http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 16/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary mentioned earlier, the congressional delegation gave their support to Crawford on the first ballot. Though Indiana had a split popular vote (like Ohio and Illinois), Jackson was able to win their support. This brings Jackson's total to seven states. Even with North Carolina and Louisiana, the total would only have been nine. If Crawford had not been in the race, it is not likely Jackson would have received his three remaining states. Delaware would have certainly gone to Adams and Virginia and Georgia could have gone either way. Thus, clearly Clay had important influence in guaranteeing Adams a first ballot victory. However, it is also clear that Jackson would have had difficulty winning in the House election under any circumstances. From Clay's Failure to Jackson's Success Clay's inability to lead public opinion and his inability to overcome the charge of 'bargain & corruption' allowed Jackson to step to the fore. It was inevitable that the West would have a major representative in national politics. Jackson seized upon Clay's political misfortune and used it to his best advantage. Shortly after the election of 1824, Jackson claimed that the office had been stolen from him by the supposed corrupt bargain between Clay and Adams. So Jackson was able to rally against bargain and corruption in the campaign of 1828. Jackson's overwhelming victory over Adams attests to his success in this crusade. The House contest polarized the political atmosphere immediately. According to Hailperin, "The years, then, between 1824 and 1828 were years of preparation for the democracy of the next thirty years. The results of the election of 1824 made the Jackson people more firmly determined to elect him in 1828. A political candidate of these years had to declare his choice of Jackson or Adams during the campaign" (Hailperin 1926:223-4). But this dichotomy did not erase the fact that the various regions of the country were still at odds and that none felt that the choice of Adams was ultimately fulfilling. Consider this comment by Paul Nagel: "While reverence for the Union may have overcome disruption in 1824, the bitter emotion then aroused left so indelible an impression that Adams took office with the foundations for dissension in place. There remained before the nation a quarter century of compromise and cajolery until the essential problems that clearly intruded in this campaign forced the sections to resolve their differences by violence" (1960, 329). In a sense, then, the election of 1824 was anomalous as it revealed the tensions other elections had managed to conceal. This analysis argues that the concept of a growing, consensual nationalism in the antebellum period is a false one and that the election of 1824 offers us a rare opportunity to assess the true nature of the political environment. The election of John Quincy Adams in 1824 was not the cause of sectional rivalries and dissent, but rather a clear expression of their scope and presence. Consequently, the analogies of 1824 to the present are somewhat different than anticipated. The fear in the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections was that the introduction of a powerful third candidate who had national appeal could force a House election as in 1824 (where the mistaken inference was that personalities would prevail). Of course, Ross Perot did not win any electoral votes. One reason is Perot's insistence on being a national candidate (that is, appearing on the ballot in all 50 states). In http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 17/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary 1824, no candidate was a national candidate. This explains why no one candidate obtained a majority of electoral votes and why many candidates won in various regions. Perot showed greater strength in the upper Midwest and the West than in most other regions of the country. Had he concentrated his efforts in those areas, it is conceivable that he would have received enough electoral votes to deny Bill Clinton a majority. Perhaps 1824 shows candidates how to broker House elections in the future. Indeed, Ross Perot's strength, especially at the expense of then-President Bush, has focused attention on the viability of a third party or independent candidate in presidential elections. Another lesson we may take from the election of 1824 about the elections of 1992 and 1996 is about what may be happening to our political party system. When there is much attention on candidates outside the traditional nominating process, we must acknowledge the weakness this implies about our own party system. The irony is that in 1824, the incoherence of the party system led to the selection of a president by the very 'insiders' who were mistrusted by the people. This `catch-22' could be on the horizon for us once again in the contemporary era. The author would like to thank Rebecca Evans, William Freehling, Glen Gaddy, Janine Holc, Robert Peabody and the anonymous reviewers for Congress & the Presidency for their comments and suggestions. [1] See for example Brown (1925), Bemis (1949), Danger field (1953), Green (1965), Remini (1981) who titles his chapter on the election "The Theft of the Presidency", and scores of history textbooks and other works on the period. [2] This is a term I borrowed from Stephen Skowronek (1993). In categorizing presidential leadership in political time, Skowronek describes the presidency of John Quincy Adams as the first to illustrate the politics of disjunction. This is defined as "...the impossible leadership situation: a president affiliated with a set of established commitments that have in the course of events been called into question as failed or irrelevant responses to the problems of the day"(Skowronek 1993, 39). Skowronek implies a no-win situation for John Quincy Adams: supported enough to be elected, but not to conduct either politics as usual or radical change. [3] Kenneth Stampp has argued that by throwing away the Articles of Confederation in favor of an entirely new document, the founding fathers were abandoning the idea of a unanimous, perpetual union, settling instead for a more consensual one. [4]According to M.J. Heale (1982) about 100 constitutional amendments concerning presidential selection and powers were proposed between 1800-1828. This was about half of all proposed constitutional amendments. [5] The number of these districts would correspond to the number of electoral votes for the state (and would be drawn by the state legislature), or alternatively the existing congressional districts and two at large districts. http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 18/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary [6] Of the 71 votes cast by this method, 36 went to John Quincy Adams, 15 to Andrew Jackson, 16 to William Crawford, and 4 to Henry Clay. If these votes are subtracted from the candidates' totals, Jackson is left with 84 votes, Adams with 48. [7] According to Nagel: "As a Southerner, and claimed by Virginians because of his birthplace, William H. Crawford found it difficult outside his section to overcome the slave region and Virginia Dynasty stigmata. Such problems superseded his more publicized caucus worries and the upshot was the familiar presentation of a man for all America" (1960, 324). Nagel thus emphasizes regional allegiance above Crawford's status as caucus nominee, a point with which I am not entirely comfortable. [8] According to Green (1965, 203), Calhoun probably wrote the following newspaper quote pertaining to Crawford: "...and by combining with many leading Northern Federalists [Crawford] would seat himself in power' against the first idea and true spirit of a republican government, THE WILL OF THE PEOPLE.'" [9] Charles Sellers (1957) also suggests that the Jackson nomination was actually a move to improve Adams' chances at the expense of both Crawford and Clay. Jackson was not considered to be a candidate with truly national appeal (as were Clay and Crawford) but could defeat them in the newer west (TN, AL, MS, LA) which Adams couldn't win anyway. [10] By the time of the election of 1824, Federalists would forget this label and support Adams overwhelmingly. [11] For evidence of this, see Nagel, 1960. Nagel's argument supports the regional issues thesis. His brief summary of period newspaper editorials portrays a pervasive preoccupation with the ability of any one of the `regional' candidates to lead the whole nation effectively. [12]The opposition to Crawford in the Virginia popular vote was split between Adams and Jackson. Adams's support can be explained in two ways: the anti-slavery views of Western Virginians and the reluctance to embrace Jackson's egalitarian views. [13] One of Clay's closest associates, Thomas Hart Benton, testifies to this: "It came within my knowledge (for I was then intimate with Mr. Clay) long before the election, and probably before Mr. Adams knew it himsell that Mr. Clay intended to support him against General Jackson, and for the reasons afterward averred in his public speeches" (Benton 1854, 48). [14]A claim which, though powerful on the contemporary political consumer, has been challenged here. [15] Consider the conclusions of William G. Morgan who surveyed a large number of works on the http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 19/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary subject: "Though the consensus favors Adams and Clay, certain respected historians have sided with Jackson in asserting that a corrupt bargain did occur....There is thus not only a variety of basic conclusions, but also a number of relative positions on the spectrum. A further difference exists concerning the sources used to justify each approach. Some writers emphasize Clay's letters and speeches; others rely primarily on Adams' diary; still others base their conclusions on the statements of Jackson and his lieutenants; some commentators focus on Buchanan's activities and letters. But few historians have effectively utilized all these materials." (Morgan, 1967:57). DIAGRAM: Figure 1: Relationship Of Issues and Candidates MAP: Figure 2: Popular Vote- 18241 MAP: Figure 3: Electoral College Vote- 1824 MAP: Figure 4: House Election- 1824 Adams, John Quincy. 1875. Memoirs. 12 vols. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. Baxter, Maurice G. 1995. Henry Clay and the American System. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press. Bemis, Samuel Flagg. 1949. John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy. New York: Alfred Knopf. Benton, Thomas Hart. 1854. Thirty Years' View. New York: D. Appleton Co. Brown, Everett S. 1925. "The Presidential Election of 1824-5". Political Studies Quarterly 40: 384403. Clay, Henry. 1963. The Papers of Henry Clay. 9 vols. Lexington, KY.: University of Kentucky Press. Dangerfield, George. 1953. The Era of Good Feelings. London: Methuen. Eaton, Clement. 1957. Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston: Little, Brown & Co. Follett, Mary Parker. 1896. The Speaker of the House of Representatives. New York: Longmarts, Green & Co. Francis, Samuel. 1991. "Henry Clay and the Statecraft of 15:45-67. Freehling, William W. 1990. The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854. New York: Oxford University Press. http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 20/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary Green, Philip Jackson. 1965. The Life of William Harris Crawford. Charlotte, NC: n.p. Hailperin, Herman. 1926. "Pro-Jackson Sentiment in Pennsylvania, 1820-1828." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 50:193-240. Hailer, Mark H. 1962. "The Rise of the Jackson Party in Maryland, 1820-1829." The Journal of Southern History 28:307-326. Hargreaves, Mary W. M. 1985. The Presidency of John Quincy Adams. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Heale, M.J. 1982. The Presidential Quest: Candidates and Images in American Political Culture. London: Longman. Johnson, Gerald W. 1939. America's Silver Age: The Statecraft of Clay-Webster-Calhoun. New York: Harper & Brothers. Kohl, Lawrence Frederick. 1989. The Politics of Individualism: Parties and the American Character in the Jacksonian Era. New York: Oxford University Press. McCormick, Richard E 1960. "New Perspectives on Jacksonian Politics." American Historical Review 65:288-301. ---.1982. The Presidential Game: The Origins of American Presidential Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. Morgan, William G. 1967. "John Quincy Adams Versus Andrew Jackson: Their Biographers and the `Corrupt Bargain' Charge." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 26:43-58. Nagel Paul C. 1960. "The Election of 1824: A Reconsideration Based on Newspaper Opinion." Journal of Southern History 26:315-329. Ostrogorski, Mosei. 1900. "The Rise and Fall of the Nominating Caucus, Legislative and Congressional." American Historical Review 5:249-268. Peterson, Svend. 1963. A Statistical History of the American Presidential Elections. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. Rammelkamp, C. H. 1905. "The Campaign of 1824 in New York." Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1904. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 21/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary Ratcliffe, Donald J. 1973. "The Role of Voters and Issues in Party Formation: Ohio, 1824." The Journal of American History 59:847-870. Remini, Robert V. 1981. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom: 1822-1832. Volume 1I. New York: Harper & Row. Remini, Robert V. 1991. Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union. New York: W.W. Norton. Roseboom, Eugene M. 1917. "Ohio in the Presidential Election of 1824." Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 26:153-224. Sellers, Jr., Charles Grier. 1957. "Jackson Men with Feet of Clay." American Historical Review 62:53751. Skowronek, Stephen. 1993. The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from John Adams to George Bush. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Stampp, Kenneth M. 1980. The Imperiled Union: Essays on the Background of the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Stanwood, Edward. 1884. AHistory of Presidential Elections. Boston: James R. Osgood & Co. Stenberg, Richard R. 1934. "Jackson, Buchanan, and the 'Corrupt Bargain' Calumny." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 58:61-85. Taylor, George Rogers. 1964. The Transportation Revolution: 1815-1860. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Thompson, Robert R. 1991. "John Quincy Adams, Apostate: From `Outrageous Federalist' to 'Republican Exile' 1801-1809." Journal of the Early Republic. 11:161-183. Thornton Ill, J. Mills. 1978. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. Wire, Richard Arden. 1973. "John M. Clayton and the Rise of the Anti-Jackson Party in Delaware." Delaware History 15: 256-268. Wood, Gordon S. 1988. "The Significance of the Early Republic." Journal of the Early Republic 8: 1-20. Zagarri, Rosemarie. 1987. The Politics of Size: Representation in the United States, 1776-1850. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. By Robin Kolodny, Temple University http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 22/23 7/9/2014 Module Creator - Module Summary http://modulecreator.com/ModuleCreator/#moduleId=36297&step=ReviewandPublish&page=review 23/23