Document 14277359

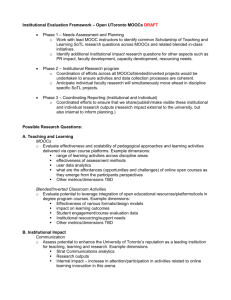

advertisement