L R S

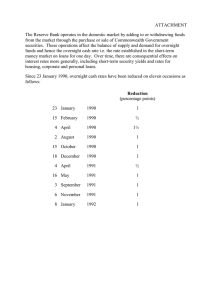

advertisement