– Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13 Ed.)

advertisement

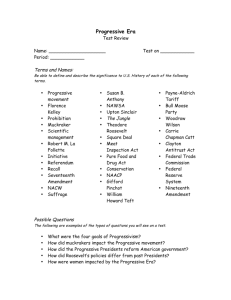

AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. Progressivism and the Republican Roosevelt, 1901 – 1912 Before studying Chapter 28, read over these “Themes”: Theme: The strong progressive movement successfully demanded that the powers of government be applied to solving the economic and social problems of industrialization. Progressivism first gained strength at the city and state level, and then achieved national influence in the moderately progressive administration of Theodore Roosevelt. Theme: Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor, William H. Taft, aligned himself with the Republican Old Guard, causing Roosevelt to break away and lead a progressive third-party crusade. After studying Chapter 28 in your textbook, you should be able to: 1. Discuss the origins and nature of the progressive movement. 2. Describe how the early progressive movement developed its roots at the city and state level. 3. Identify the critical role that women played in progressive social reform. 4. Tell how President Roosevelt began applying progressive principles to the national economy. 5. Explain why Taft’s policies offended progressives, including Roosevelt. 6. Describe how Roosevelt led a progressive revolt against Taft that openly divided the Republican Party. Know the following people and terms. Consider the historical significance of each term or person. Also note the dates of the event if that is pertinent. A. People Henry Demarest Lloyd Thorstein Veblen Jacob Riis Lincoln Steffens Theodore Dreiser Ida Tarbell Robert M. La Follette Hiram Johnson Francis Willard Florence Kelley +J.P. Morgan John Muir Gifford Pinchot Eugene V. Debs Nelson W. Aldrich Charles Evans Hughes Upton Sinclair William Howard Taft Richard Ballinger +Rachel Carson AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. B. Terms: progressive initiative referendum recall difference between conservation and preservation “rule of reason” Muckrakers *Sixteenth Amendment *Seventeenth Amendment Eighteenth Amendment *Keating-Owen Child Labor Act (1916) Elkins Act Hepburn Act Northern Securities Supreme Court case Women’s Trade Union League Muller v. Oregon Lockner v. New York Triangle Shirtwaist fire Meat Inspection Act Pure Food and Drug Act Newlands Act Sierra Club Yosemite National Park dollar diplomacy Payne-Aldrich Act Dollar diplomacy Ballinger-Pinchot affair Old Guard +=One of the 100 Most Influential Americans of All Time, as ranked by The Atlantic. Go to Webpage to see all 100. *=A 100 Milestone Document from the National Archive. Go to Webpage to link to these documents. C. Sample Essays: Using what you have previously learned and what you learned by reading Chapter 28, you should be able to answer an essay such as this one: The textbook states that the *Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine distorted the original policy statement of 1823. Did it? Compare the purposes of the two policies. D. Can you explain why? The Spanish-American War lasted 3 months. The Philippine insurrection lasted 3 years. Can you explain why virtually every American history textbook devotes several times more space to the war than to the insurrection? AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. E. Interpreting Political Cartoons: Look at the cartoon and answer the questions below it The World's Policeman 1. What is the title of this cartoon? ________________________________________________ 2. Who is the big man in the middle of the cartoon? ___________________________________ 3. What new “policy” is the cartoon commenting on? __________________________________ 4. What famous Roosevelt saying is represented in this cartoon? ________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ 5. How are stereotypes being used? _______________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ 6. How is geography being manipulated? ___________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ 7. Is the cartoon supportive or critical of Roosevelt? Explain: ___________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ F. How do you analyze political cartoons? Use the following diagram: AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. Cartoon Analysis Worksheet Level 1 Visuals Words (not all cartoons include words) 1. Identify the cartoon title. 1. List the objects or people you see in the cartoon. 2. Identify the cartoon captions (Who is saying what? Are they real or symbolic?) 3. Locate three words or phrases used by the cartoonist to identify objects or people within the cartoon. 4. Record any important dates or numbers that appear in the cartoon. Level 2 Visuals Words 2. Which of the objects on your list are symbols? 5. Which words or phrases in the cartoon appear to be the most significant? Why do you think so? 3. What do you think each symbol means? 6. List adjectives that describe the emotions portrayed in the cartoon. Level 3 A. Describe the action taking place in the cartoon. B. Explain how the words in the cartoon clarify the symbols. C. Explain the message of the cartoon. D. What special interest groups would agree/disagree with the cartoon's message? Why? AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. Theodore Roosevelt in Political Cartoons David C. Hanson, Virginia Western Community College In the early twentieth century, the proliferation of newspapers and pulp magazines with wide circulation provided the perfect vehicle for political cartoonists to communicate their commentaries. Political cartoons in America go back to the colonial era, such as a 1765 engraving by Paul Revere protesting the Stamp Act. Once the new nation was founded, Republicans attacked Washington and other Federalists in scathing cartoons, and the Federalists retaliated against Jefferson and his party. Jackson was assailed in numerous caricatures, as was Lincoln. Then in the late nineteenth century, Thomas Nast perfected the art, creating the enduring symbols of the elephant for Republicans and the donkey for Democrats. His cartoons attacking “Boss” Tweed, boss of New York's Tammany Hall machine, probably played an important role in Tweed's demise. Tweed was an ideal target, but no political figure was more perfectly suited for the art of political cartoons than Theodore Roosevelt. "His gleaming, oversized front teeth, bull neck, pince-nez glasses, and of course, big stick begged to be caricatured. Cartoonists did not have to stretch the imagination to cast Teddy larger than life; he specialized in that department long before he reached the White House" [James Davidson and Mark Lytle, After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection]. Origin of the Teddy Bear Roosevelt was an avid outdoorsman and hunter. He once refused to shoot a small bear on a Mississippi hunting trip and the incident led to the origin of the "teddy bear" as a popular child's toy. His bear friend became a common sidekick in many subsequent cartoons. (Cartoon by Clifford Berryman) G. What was the Progressive Movement? Read on to find out AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. The Progressive Movement The Progressive Movement was an effort to cure many of the ills of American society that had developed during the great spurt of industrial growth in the last quarter of the 19th century. The frontier had been tamed, great cities and businesses developed, and an overseas empire established, but not all citizens shared in the new wealth, prestige, and optimism. Efforts to improve society were not new to the United States in the late 1800s. A major push for change, the First Reform Era, occurred in the years before the Civil War and included efforts of social activists to reform working conditions, and humanize the treatment of mentally ill people and prisoners. Others removed themselves from society and attempted to establish utopian communities in which reforms were limited to their participants. The focal point of the early reform period was abolitionism, the drive to remove what in the eyes of many was the great moral wrong of slavery. The Second Reform Era began during Reconstruction and lasted until the American entry into World War I. The struggle for women's rights and the temperance movement were the initial issues addressed. A farm movement, known as the Populists, also emerged to compensate for the declining importance of rural areas in an increasingly urbanized America. As part of the second reform period, Progressivism was rooted in the belief, certainly not shared by all, that man was capable of improving the lot of all within society. As such, it was a rejection of Social Darwinism, the position taken by many of the rich and powerful figures of the day. Progressivism was also imbued with strong political overtones and rejected the church as the driving force for change. Specific goals included: 1. The desire to remove corruption and undue influence from government through the taming of bosses and political machines; 2. The effort to include more people more directly in the political process; 3. The belief that government must play a role to solve social problems and establish fairness in economic matters. The success of Progressivism owed much to publicity generated by the muckrakers, writers who detailed the horrors of poverty, urban slums, dangerous factory conditions, and child labor, among a host of other ills. The successes were many, such as the Interstate Commerce Act (1887) and the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890). Progressives never spoke with one mind and differed sharply over the most effective means to deal with the ills generated by the trusts; some favored an activist approach to trust-busting, others preferred a regulatory approach. A vocal minority supported socialism with government ownership of the means of production. Other Progressive reforms followed in the form of a conservation movement, railroad legislation, and food and drug laws. The Progressive spirit also was evident in new amendments added to the Constitution, which provided for a new means to elect senators (17th), protect society through prohibition (18th), and extend suffrage to women (19th). Urban problems were addressed by professional social workers who operated settlement houses (Jane Addams) as a means to protect and improve the prospects of the poor. However, efforts to place limitations on child labor were routinely thwarted by the courts. The needs of Blacks and Native Americans were poorly served or served not at all — a major shortcoming of the Progressive Movement. Progressive reforms were carried out not only on the national level, but in the states and municipalities of the country as well. Prominent governors devoted to change included Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin and Hiram Johnson of California. Such reforms as the direct primary, secret ballot, initiative, referendum and recall were effected. Local governments were strengthened by the widespread use of trained professionals, particularly with the city manager system replacing the all-too-frequently corrupt mayoral system. H. What was the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and why was it significant to the progressive movement? Read the following article to find out: AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. AMERICAN HISTORY - APRIL 2006 - A DAY TO REMEMBER By Charles Phillips March 25, 1911 - Triangle Shirtwaist Fire At the end of the work day on March 25, 1911, Isidore Abramowitz, a cutter at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company located in the heart of Manhattan’s Garment District, had already pulled his coat and hat down from their peg when he noticed flames billowing from the scrap bin near his cutting table. It was about 4:40 PM, and within minutes the fire swept through the factory and killed more than 140 of the 500 people who worked there. The conflagration, for some 90 years considered the deadliest disaster in New York City history, would usher in an era of reform with implications far beyond those of mere workplace safety. The Jewish and Italian immigrants working at Triangle, most of them young women, produced the fashionable shirtwaists — women’s blouses loosely based on a man’s fitted shirt — popularized by commercial artist Charles Dana Gibson, whose famous “Gibson Girl” had become the sophisticated icon of the times. Beginning in late 1909, these workers participated in a major strike led by the Women’s Trade Union League demanding a shorter working day and a livable wage. The garment workers had also protested the deplorable working conditions and dangerous practices of the industry’s sweatshops. A large proportion of these firetraps, like Triangle, were located in Manhattan’s crowded Lower East Side. The factory workers had support not only from the left wing of the American labor movement but also among the city’s wealthy progressives. Such socially prominent women as Anne Morgan and Alva Belmont ensured tremendous publicity for the strikers, and they helped stage a huge rally at Carnegie Hall on January 2, 1910. But they met with adamantine resistance from factory owners, led by Triangle partners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, who hired thugs from a private detective agency to break up the strike. The owners in general enjoyed the backing of Tammany Hall boss Charles F. Murphy, which meant not only that the New York police were hostile to the workers but that strikebreakers were also available from the street gangs employed as muscle by Murphy’s political machine. When the strike ended, the owners had agreed to some minor concessions and the radical newspaper The Call declared the strike a victory. But little had changed, and everyone on the Lower East Side knew it. The workers at Triangle still put in long hours for low wages, without breaks, in an airless factory located on the top three floors of a hazardous 10story firetrap. Scraps from the pattern cutters piled up in open bins and spilled over at the workers’ feet, where the higher paid cutters, often men, dropped the ashes or even tossed the smoldering butts of the cheap cigars they smoked. Because Blanck and Harris feared pilfering by their employees, access to the exits was limited, despite the city’s fire regulations. At closing, workers were herded to the side of the building facing Greene Street, where partitions had been set up to funnel one worker at a time toward the stairway or the two freight elevators before they could leave the building for the day. This allowed company officials to inspect each exiting employee and his or her belongings for stolen tools, fabric or shirtwaists. The stairway and passenger elevators on the opposite side of the building, facing Washington Place, were reserved for management and the public. The only other egress was a narrow and flimsy fire escape on the back side of the building, opposite Washington Place, that corrupt city officials in 1900 had allowed Blanck and Harris to substitute for the third stairway legally required by the city. Access to it was partially blocked by large worktables. These arrangements all fed the disaster when the fire broke out as the result of a match or a smoldering cigarette or cigar tossed into Abramowitz’s scrap bin. The loosely heaped scraps of sheer cotton fabric and crumpled tissue paper flared quickly, and the fire was blazing within seconds. Accounts of the chaos that erupted vary greatly, but apparently Abramowitz reached up, grabbed one of the three red fire pails on the ledge above his coat rack, and dumped it on the flames. Other cutters snatched pails and tried in vain to douse the exponentially spreading blaze. Despite their efforts, the fabric—laden 01d structure, ironically called the Asch Building, began to burn quickly and fiercely. Factory manager Samuel Bernstein directed his employees to break out the fire hoses, only to find them completely useless. Some claimed the uninspected hoses had rotted through, while others asserted that either the water tanks on the roof were empty or the flow of water from them was somehow blocked. Having lost precious minutes in fruitless attempts to control the blaze, the workers looked for the means of escape. A few rushed to the solitary, poorly constructed and inadequately maintained fire escape, which descended from the 10th floor to the 2nd, stopping above a small courtyard. Some of the young women who used it fell from one landing to the next; one of the male employees fell from the 8th floor to the ground. Others madly rushed toward the inward-opening doors on the Washington Place side, preventing them from being opened. (Some later claimed these doors were locked.) As more and more workers piled up at the doors, those at the front were nearly crushed. Only with great effort did Louis Brown, a young shipping clerk, bully his way through the pressed bodies and muscle them away from the exit so that he could open the doors. On the opposite side of the building, panicked workers who tried to exit the 8th floor on the Greene Street side were slowed by the funneling partitions, and found the stairway and elevators already jammed with workers fleeing from the 9th and 10th floors. Afterward, there was much confusion and a lot of debate about which floor the Washington Place passenger elevators visited and when. The elevator operators—Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillo — certainly risked their lives by returning to burning floors to carry their co-workers to safety They probably visited the 8th floor first, saving a lot of lives even as the AP United States History - Terms and People – Unit 9, Chapter 28 (13th Ed.) HONOR PLEDGE: I strive to uphold the vision of the North Penn School District, which is to inspire each student to reach his or her highest potential and become a responsible citizen. Therefore, on my honor, I pledge that I have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work. panic there set in. Then they headed up to the 10th floor, the executive floor. Zito later guessed that they went to 10 twice, dropping off the first group only to find the floor empty on the next trip up. All 70 workers on the 10th floor managed to escape, as did Blanck (and the two daughters he’d brought to work with him) and Harris, who showed a good deal of bravery in his efforts to save many of his 10th-floor employees. They all got out either by the early elevator trips, by way of the staircases or by ascending to the roof New York University law students in a taller, adjacent building lowered ladders to the roof of the Asch Building, and the workers inched their way up them to safety Of all the Triangle employees, the 260 who worked on the 9th floor suffered the worst fate. According to some accounts, the alert and the fire reached them at the same time. The Greene Street exit was quickly jammed, and the doors to the Washington Place stairwell were found to be locked. Since the elevator car itself was packed with 10th-floor employees, some clambered down the greasy cables of the freight elevator. Elevator operator Zito peered up the elevator shaft as those left behind faced grim choices. “The screams from above were getting worse,” he later reported. “I looked up and saw the whole shaft getting red with fire....They kept coming down from the flaming floors above. Some of their clothing was burning as they fell. I could see streaks of fire coming down like flaming rockets.” Others on the 9th floor wedged their way into the Greene Street staircase and climbed up to the roof. Still others ran to the fire escape, which proved incapable of supporting the weight of so many. With an ear-rending rip, it separated from the wall, disintegrating in a mass of twisted iron and falling bodies. In complete desperation, some 9th-floor workers fled to the window ledges. The firemen’s ladders would not reach beyond the 6th floor, so the firefighters deployed a safety net about 100 feet below, and they exhorted the victims to jump. Some of the young women, in tenor, held hands and jumped in pairs. But the weight of so many jumpers split the net and young men and women tore through it to their deaths. An ambulance driver bumped his vehicle over the curb onto the sidewalk, hoping against hope that jumpers might break their fall by landing on his roof. Deliverymen pulled a tarpaulin from a wagon and stretched it out. The first body to hit it ripped it from their hands. “The first ten [to hit] shocked me,” wrote reporter William Gunn Shepherd before he looked up and saw all the others raining down. Fifteen minutes after the fire started the firemen—even then New York’s finest, the pride of the city—were within moments of bringing the fire on the 8th floor under control. But the 9th was hopeless. On the 9th, the fire took over the entire floor. Later, burned bodies were found piled up in a heap in the loft. A second scorched cluster was discovered pressed up against the Greene Street exit, where they had been caught by the blaze before they could get out. At the time, the crowds watching could see groups of girls trapped in burning window frames, refusing to jump. When they could hold out no longer, they came tumbling through the windows in burning clumps. Then it was over. The last person fell at about 4:57 p.m., and there was nothing left to do but deal with the dead— 146 broken bodies. During the next few days, streams of survivors and relatives filed through the temporary morgue on 26th Street to identify the dead. Eventually, all but six were given names. Even before the bodies stopped falling, veteran newsman Herbert Bayard Swope had interrupted District Attorney Charles Seymour Whitman’s regular Saturday news briefing at his apartment in the Iroquois Hotel to announce the disaster. Whitman immediately rushed to the scene and began looking for somebody to blame. Since he couldn’t go after the city itself, he got a grand jury to charge Blanck and Harris with negligent homicide for locking the doors to the back stairway. Defended in a celebrated trial by famed Tammany mouthpiece Max D. Steuer, himself a former garment worker, the “Shirtwaist Kings” were acquitted, much to the outrage of progressives everywhere. But watching the fire that day was a young woman named Frances Perkins. Perkins happened to be enjoying tea with a friend who lived on the north side of Washington Square. She heard the fire engines and arrived just in time to see the bodies begin to fall. Already a rising star in the progressive firmament, she never forgot what she saw, and she never let it go. Through her efforts, and the efforts of others like her, the horrible images of the Triangle fire brought an anguished outcry for laws to compel heedless, greedy, cost— cutting manufacturers to provide for the safety of employees. The pre-fire strikes, coupled with the Triangle disaster and its aftermath, unified union organizers, college students, socialist writers, progressive millionaires and immigrant shop workers. Tammany Hall boss Murphy quickly sensed that a transformation of the Democratic Party could take advantage of this new progressive coalition at the ballot box. As a result, he fully supported the New York Factory Investigating Commission, formed three months after the fire, to inspect factories throughout the state. The “Tammany Twins,” Alfred E. Smith and Robert F Wagner, who were the driving force behind the investigation, backed Perkins as she sat on the commission and took the lead in shaping its findings. The commission’s report, compiled during 2 ½ years of research, brought dramatic changes to existing laws and introduced many new ones. Smith, of course, went on to become governor of New York and the Democratic nominee for the presidency in 1924 and 1928. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt followed in his footsteps and actually won election to the office in 1932, he brought Perkins with him into his New Deal, as the first female Cabinet member (Secretary of Labor), and Wagner as an adviser who drafted some of the most important progressive legislation in the country’s history. In many ways, it is fair to say that the modern American welfare state of the 20th century’s middle decades rose from the ashes of the Triangle fire.