Document 14123725

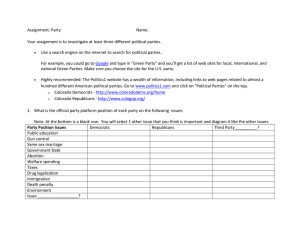

advertisement