Socioeconomic Gradients in Early Child Health Across Race, Ethnicity and Nativity National Poverty Center Working Paper Series

National Poverty Center Working Paper Series

#06 ‐ 21

June, 2006

Socioeconomic

Gradients

in

Early

Child

Health

Across

Race,

Ethnicity

and

Nativity

Lenna

Nepomnyaschy,

Columbia

University

This paper is available online at the National Poverty Center Working Paper Series index at: http://www.npc.umich.edu/publications/working_papers/

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the National Poverty Center or any sponsoring agency.

Socioeconomic Gradients in Low Birth Weight across Race and Ethnicity

Lenna Nepomnyaschy

Columbia University

This work has been supported by a grant from the National Poverty Center at the University of

Michigan. Any opinions expressed are those of the author. I would like to thank Julien Teitler and Nancy Reichman for their advice and suggestions.

1

2

Abstract

This paper examined socioeconomic gradients in low birth weight across a number of racial and ethnic groups in the United States, using a new nationally representative study of children born in 2001 (n = 8,650). The data include oversamples of several minority groups and a rich set of demographic, family, health, and health behavior characteristics. Proportion of low birth weight

(and 95% CIs) across categories of income and maternal education was presented for the pooled sample of children and disaggregated by race/ethnicity: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black,

Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian. A strong graded association was found for the pooled sample between both income and education and low birth weight. When disaggregating by race/ethnicity, the income gradient was evident only for whites and Hispanics, while the education gradient was found only for whites. Blacks had the highest rates of low birth weight across all socioeconomic categories (of any group) and the largest black/white disparities were found in the top of the income and education distributions. These findings have important implications for identifying the sources of disparities in low birth weight and understanding the meaning of socioeconomic status across groups in the US.

Keywords: Infant, low birth weight; socioeconomic factors; ethnic groups

3

There are large disparities in infant health by socioeconomic status (SES) in the United

States. Low SES mothers are much more likely to have poor birth outcomes than are mothers of higher SES (1, 2). It is well established that there is a graded relationship between adult health and socioeconomic status throughout the entire SES distribution (3-5). SES gradients have also been found for numerous measures of child health (6-12), with some evidence that gradients become steeper as children age (6, 7, 11, 12). Studies that have examined birth outcomes (13-23) have also found SES gradients, though the results are not consistent across outcomes and measures of SES.

There are also well-established disparities in birth outcomes by race/ethnicity in the U.S.

Non-Hispanic black children have much higher rates of infant mortality, preterm birth and low birth weight than white children (24, 25). For black children, these disparities are not surprising, since they are also much more likely to be poor than white children. However, Mexican and

American Indian children have similar or better birth outcomes than non-Hispanic white children, despite much lower socioeconomic status (25-28). This ‘epidemiologic paradox’ (29) suggests that the association between SES and birth outcomes is not similar across racial and ethnic groups. Graded associations between maternal education (as a proxy for SES) and low birth weight have been found for whites and blacks (15-18, 30), though generally weaker for blacks. Only a few studies have examined gradients for other groups and have found much weaker or non-existent associations for Hispanics and Asians (17, 22).

Maternal education is the most commonly used measure of SES in research on infant health, because of the lack of broader measures in most data. Studies that used different indicators of SES found that results were sensitive to the indicator used (15, 23). The variability

4

in the associations of infant health with SES across race and ethnicity and by SES indicator is consistent with the idea of differential returns to human capital by race and ethnicity (31-33).

This study drew on a new nationally representative birth cohort of young children to investigate how two indicators of socioeconomic status (maternal education and household income) are associated with low birth weight for non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks,

Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians. The associations were adjusted by a rich set of potential mediators, including demographic characteristics, maternal health, and health behaviors. Understanding how the SES/low birth weight association differs across groups is vital to identifying the sources of disparities in birth outcomes and understanding the meaning of socioeconomic status across groups in the U.S.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was based on data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey–Birth Cohort

(ECLS-B), a nationally representative study of over 10,000 children born in the U.S. in 2001.

Births were sampled from Vital Statistics records and consist of children born in 2001 who were alive at the 9-month baseline interview (34). The ECLS-B includes oversamples of several minority populations which have not been the focus of most prior nationally representative surveys, including American Indians, Chinese, and other Asians and Pacific Islanders. The current study is based on interviews with mothers when the infant was 9 months old (baseline), to which birth certificate data were appended. The final sample consists of 8,650

1

singleton births for whom the biological mother was the main respondent, and who were non-missing on birth weight and race/ethnicity.

1

All unweighted sample sizes have been rounded to the closest 50 as required by the National Center for Education

Statistics (NCES).

5

Low birth weight (< 2500 grams) was assessed from birth certificates (BC). Socioeconomic status was assessed using maternal survey reports (SR) of her education (less than high school, high school degree, some college, or college degree or better), and total household income in the past year (<=$15,000, $15,001-$30,000, $30,001-$50,000, or >$50,000). The mother’s race and ethnicity (BC) was classified as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, or non-Hispanic American Indian. Models controlled for the following: maternal age (BC) (less than 21, 21-30, or 31 and older), marital status (BC), whether this was the mother’s first birth

(BC), child’s sex (SR), number of people in the family (SR), whether the mother lived with both biological parents until age 16 (SR), region of residence (SR), maternal smoking during pregnancy (either BC or SR), prenatal care in first trimester (BC), and presence of any prenatal medical risk factors (BC) including anemia, cardiac or lung disease, diabetes, hypertension, eclampsia, previous low birth weight or preterm birth, or other medical risk factors.

Means for low birth weight incidence, socioeconomic status and all covariates were compared across racial/ethnic groups. Tests of statistical significance (t-tests for binary and continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables) were used to identify significant differences on each measure between white and all other racial/ethnic groups.

Associations (adjusted only by child sex) between levels of income and education and low birth weight were graphed as predicted probabilities (and 95 percent confidence intervals) from logistic regressions for the pooled sample of infants and then separately by racial/ethnic category. These associations were then adjusted by demographic characteristics (child sex, mother’s age at birth, marital status, number of people in the family, mother’s family background, urban residence, and region of residence), medical risk factors, and health behaviors

(smoking during pregnancy and early prenatal care). All analyses were performed using Stata 9

6

SE statistical software package, were based on weighted data, and were adjusted for design effects using the SVY set of commands in Stata (Statacorp 2003).

RESULTS

Of the full sample of 8,650 singleton infants, 5.8 percent were low birth weight (from table 1). Children of non-Hispanic black mothers were more than twice as likely to be low birth weight as those of non-Hispanic white mothers (10.5 vs. 4.9 percent). No other group had low birth weight rates that were significantly different from those of whites.

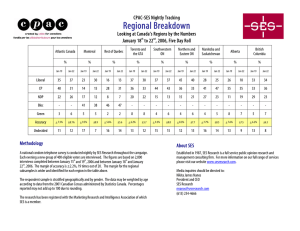

SES varied substantially across groups. Only 9 percent of Chinese, 11 percent of white, and 8 percent of Asian children were in households with income of $15,000 or less, while 40 percent of black and over one-third of American Indians were in this group. Conversely, only 15 percent of black and Hispanic and 16 percent of American Indian families had over $50,000 of income, while about half of white and Asian families were in this group. A somewhat similar, though not identical, pattern is evident for maternal education. Over half of Hispanic and more than one-third of black and American Indian mothers have less than a high school education, and only about 10 percent of mothers in these three groups have completed college.

Over one-quarter of black and American Indian mothers were less than 21 years old at the child’s birth, compared with only 8 and 12 percent of Asian and white mothers. Almost 90 percent of Asian mothers were married at the child’s birth, while only one-third of black mothers were married. Similarly, just over one-third of black and American Indian mothers lived with their own biological parents till age 16 compared with 60 percent of white and Hispanic mothers and almost 80 percent of Asian mothers.

American Indian and white mothers (26 and 19 percent) reported much higher levels of smoking during pregnancy than any other group, with only 11 percent of black mothers and 3

7

percent of Hispanic and Asian mothers in this group. All the minority groups were less likely to have had prenatal care in the first trimester than white mothers, with only three-quarters of black,

Hispanic and American Indian mothers having early prenatal care. Hispanic and Asian mothers were both less likely to have had any medical risk factor during pregnancy than were white mothers, while black and American Indian mothers did not differ significantly from white mothers on this measure.

Figure 1 presents the proportion (adjusted for child sex) and 95 percent confidence intervals of low birth weight at each level of income and education for the pooled sample of mothers. There is a clear monotonic association between low birth weight and income, with each categorical increase in income leading to a lower rate of low birth weight. There is a similar decline in proportion low birth weight as education increases, but the benefit of education is only realized for those with some college or more.

Figures 2 and 3 present these associations separately across race/ethnicity. A graded relationship between income and low birth weight is apparent for whites and Hispanics (though less significantly so for Hispanics). At each level of income, Hispanic mothers have a slightly lower rate of low birth weight than white mothers. There does not appear to be an association between income and low birth weight for blacks. Since blacks benefit less from higher income than do whites, the low birth weight rate for blacks in the top income group remains higher than for the poorest whites, and the disparity in low birth weight between blacks and whites increases as income increases. There is no clear association between income and low birth weight for

Asians and American Indians. For the latter group, improvements at the lower levels of income are offset by an increase in rates of low birth weight for those at the top.

8

The associations between education and low birth weight (figure 3) also vary by race and ethnicity. For whites, the graded association is even stronger than it was for income. For blacks, the association is not monotonic and differences across education categories are not statistically significant. As for income, black/white disparities are greatest for those at the highest levels of education. Among Hispanics, there is no benefit of higher education, but actually weak evidence of a negative gradient, where more education is associated with higher rates of low birth weight.

Higher levels of education appear to confer no benefit for reducing low birth weight for any of the other racial/ethnic groups.

Figure 4 presents proportion low birth weight by levels of income across racial/ethnic groups adjusted by the previously discussed demographic, maternal health, and health behavior characteristics. The adjusted figures are very similar to the unadjusted proportions in figure 2, indicating that the racial and ethnic differences in associations of SES and birth weight are not due to differences across groups in the distribution of risk factors.

DISCUSSION

This paper examined the relationship between two measures of SES and low birth weight across race and ethnicity. Consistent with prior research, income and education gradients were found for low birth weight in the pooled sample of children (13, 15). There was no evidence of a threshold effect in these data, contrasting with at least one prior study (13). Higher income had beneficial effects on low birth weight throughout the entire distribution; however, the payoff for education was only observed for those who had some college or more.

When disaggregating the sample by race/ethnicity, the graded association between both income and education and low birth weight was observed mostly for whites. A weaker income gradient for low birth weight was also evident for Hispanics, but there was no education

9

gradient. There was no evidence of a significant association between education and low birth weight for any group other than non-Hispanic whites. The presence of an income/low birth weight gradient found for Hispanics is in contrast with some prior research on birth outcomes and other measures of child health, which generally did not find a gradient using mothers’ education as the measure of SES (8, 17, 22). These findings highlight the problem of using mothers’ education as the sole measure of SES in health studies. Hispanics are much more likely to have no high school diploma (lowest education category), but are much less likely to be in the bottom income category than either blacks or American Indians.

A consequence of the steeper income and education gradients found for whites than for other groups is that racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes vary across the SES distribution. Black-white disparities in low birth weight are large even at low levels of SES and increase as income and education increase. Asians and American Indians have favorable outcomes at low levels of SES but their advantage over whites dissipates at higher levels of SES.

Hispanics, too, have fewer low birth weight infants than whites at low levels of SES, but have a less consistent pattern based on SES indicator. Hispanics quickly lose their advantage over whites at higher levels of education, but maintain their advantage at higher levels of income.

The fact that the relationship between income and low birth weight persisted after including a rich set of controls for demographic, maternal health and health behavior characteristics suggests that those risk factors are not explaining cross-group differences in SES gradients, and is consistent with Link and Phelan’s (4) theory of the ‘fundamental causes of disease’, which suggests that other resources such as power, knowledge, prestige, social support and social networks lead to health disparities.

10

One cautionary note is that Hispanics in the ECLS-B data are made up of mostly (twothirds) Mexicans. Other Hispanics are of Central and South American, Puerto Rican, Cuban and unknown origin. Because these groups have substantial differences in health risks, SES, and infant health, the findings for all Hispanics could be driven largely by Mexicans and may conceal heterogeneity across Hispanic subgroups. In supplementary analyses, Mexicans and other

Hispanics were examined separately, and the results yielded similar patterns. Similarly, Chinese make up the largest proportion of Asians in these data (one-third), with much smaller numbers of

Japanese, Philippinos, Koreans, and Vietnamese. These Asian sub-groups also have very different demographic, SES, and health profiles.

By pointing to race and ethnic differences in returns to socioeconomic status, this study raises important questions about the causes of health disparities. It appears that blacks,

Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians in the United States do not reap the same health benefits from higher socioeconomic status as do whites. This suggests that social mobility is experienced differently by race and ethnicity. Little is known about how the determinants and consequences of social mobility differ across groups. The answers to these questions are likely to provide insights into the causes of health disparities.

11

REFERENCES

1. Kramer MS, Seguin L, Lydon J, Goulet L. Socio-economic disparities in pregnancy outcome: Why do the poor fare so poorly? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2000;14(3):194-210.

2. Aber JL, Bennett NG, Conley DC, Li J. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annu Rev of Public Health 1997;18(1):463-483.

3. Marmot MG, Kogevinas M, Elston MA. Social/economic status and disease. Annu Rev of Public Health 1987;8(1):111-135.

4. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc

Behav 1995;35(Extra Issue: Forty Years of Medical Sociology: The State of the Art and

Directions for the Future):80-94.

5. Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, et al. Socioeconomic status and health, the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol 1994;49(1):15-24.

6. Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C. Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient. Am Econ Rev 2002;92(5):1308-1334.

7. Chen E, Matthews KA, Boyce T. Socioeconomic differences in children's health: How and why do these relationships change with age? Psychol Bull 2002;128(2):295-329.

8. Chen E, Martin AD, Matthews KA. Understanding health disparities: The role of race and socioeconomic status in children's health. Am J Public Health 2006;96(4):702-708.

12

9. Starfield B, Robertson J, Riley AW. Social class gradients and health in childhood.

Ambul Pediatr 2002;2(4):238-246.

10. Goodman E. The role of socioeconomic status gradients in explaining differences in U.S. adolescents' health. Am J Public Health 1999;89(10):1522.

11. Chen E, Martin AD, Matthews KA. Socioeconomic status and health: Do gradients differ within childhood and adolescence? Soc Sci Med 2006;62(9):2161-2170.

12. Currie J, Stabile M. Socioeconomic status and child health: Why is the relationship stronger for older children? Am Econ Rev 2003;93(5):1813-1823.

13. Finch BK. Socioeconomic gradients and low birth-weight: Empirical and policy considerations. Health Serv Res 2003;38(6p2):1819-1842.

14. Finch BK. Early origins of the gradient: The relationship between socioeconomic status and infant mortality in the United States. Demography 2003;40(4):675.

15. Parker JD, Schoendorf KC, Kiely JL. Associations between measures of socioeconomic status and low birth weight, small for gestational age, and premature delivery in the United

States. Ann Epidemiol 1994;4(4):271-8.

16. David RJ, Collins JW. Differing birth weight among infants of U.S.-born blacks, Africanborn blacks, and U.S.-born whites. N Engl J Med 1997;337(17):1209-1214.17.

17. Acevedo-Garcia D, Soobader M-J, Berkman LF. The differential effect of foreign-born status on low birth weight by race/ethnicity and education. Pediatrics 2005;115(1):e20-30.

13

18. Kleinman JC, Kessel S. Racial differences in low birth weight. Trends and risk factors. N

Engl J Med 1987;317(12):749-53.

19. Pallotto EK, Collins JW, Jr., David RJ. Enigma of maternal race and infant birth weight:

A population-based study of US-born black and Caribbean-born black women. Am J Epidemiol

2000;151(11):1080-5.

20. Gould JB, LeRoy S. Socioeconomic status and low birth weight: A racial comparison.

Pediatrics 1988;82(6):896-904.

21. Collins JWJ, David RJ. The differential effect of traditional risk factors on infant birthweight among blacks and whites in Chicago. Am J Public Health 1990;80(6):679.

22. Goldman N, Kimbro RT, Turra CM, Pebley AR. Socioeconomic gradients in health for white and Mexican-origin populations. Am J Public Health 2006;96(12):2186-2193.

23. Braveman P, Cubbin C, Marchi K, Egerter S, Chavez G. Measuring socioeconomic status/position in studies of racial/ethnic disparities: Maternal and infant health. Public Health

Rep 2001;116(5):449.

24. Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2003 period linked birth/infant death data set: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Reports,

Vol. 54, No. 16; 2006.

25. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacher F, Kirmeyer S. Births: Final data for 2004: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 55,

No. 1; 2006.

14

26. Grossman DC, Baldwin L-M, Casey S, Nixon B, al e. Disparities in infant health among

American Indians and Alaska Natives in US metropolitan areas. Pediatrics 2002;109(4):627.

27. Baldwin L-M, Grossman DC, Casey S, Hollow W, Sugarman J, Freeman WL, et al.

Perinatal and infant health among rural and urban American Indians/Alaska Natives. Am J

Public Health 2002;92(9):1491-1497.

28. Fuentes-Afflick E, Lurie P. Low birth weight and Latino ethnicity. Examining the epidemiologic paradox. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151(7):665.

29. Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the Southwestern United States: An epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep 1986;101:253-265.

30. Pallotto EK, Collins JW, Jr., David RJ. Enigma of maternal race and infant birth weight:

A population-based study of US-born black and Caribbean-born black women. Am J Epidemiol

2000;151(11):1080-5.

31. Kaufman J, Cooper R, McGee D. Socioeconomic status and health in blacks and whites:

The problem of residual confounding and the resiliency of race. Epidemiology 1997;8(6):621-8.

32. Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al.

Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. JAMA 2005;294(22):2879-

2888.

33. Gazmararian JA, Adams MM, Pamuk ER. Associations between measures of socioeconomic status and maternal health behavior. Am J Prev Med 1996;12(2):108-115.

15

34. Bethel J, Green J, Kalton G, Nord C. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort

(ECLS-B), sampling. Volume 2 of the ECLS-B methodology report for the 9-month data collection, 2001–02 (NCES 2005–147). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education,

National Center for Education Statistics; 2005.

16

Table 1: Sample Description (data are weighted in all but the first two rows)

N (rounded to nearest 50)

% of Full Sample

Low birth weight (<2500 g)

Measures of SES

Household Income*

$15,000 or less

$15,001 to $30,000

$30,001 to $50,000

$50,001 or more

Mother's Education*

Less than HS

18

25

21

35

28

All

Children

8650

100%

5.8

White, non-

Hispanic

3700

43%

4.9

11

20

22

47

17

Black, non-

Hispanic

1500

17%

10.5*

40

28

17

15

34

Hispanic

1450

17%

5.4

25

38

22

15

53

8

20

22

50

17

Asian

1400

16%

5.5

American

Indian

550

7%

3.8

34

28

22

16

36

Some college 26

College +

Mothers' Demographic Characteristics

24

Categories of Age*

<21

21-30

31+

Married at birth

Male child

# of people in family a

16

53

31

67

51

4.3

First birth

Lived w/bio parents till 16

Reside in urban area

Region of family residence*

41

58

74

29

32

12

52

36

78

51

4.1

41

61

65

26

10

19

9

22

47

33

8

27

52

21

32*

20

57

23

58*

8

49

43

87*

28

52

19

45*

50 52 54 51

4.4* 4.7* 4.4* 4.5*

38

35*

84*

41

62

89*

47*

77*

93*

43

38*

47*

Maternal Health and Health Behaviors

Smoked during pregnancy

Prenatal care in first 3 months

Any medical risk factor

14

84

30

19

89

31

11*

74*

34

3*

77*

26*

* p < .10; indicates significant differences between whites and each racial/ethnic group. a

Mean number of people.

3*

86*

23*

17

24*

75*

36

18

19

20

21