Document 13957897

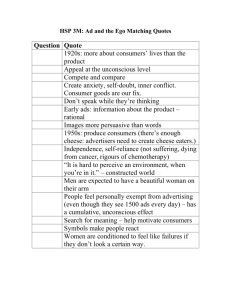

advertisement