Introduction to Mentalisation Clinical Question? A Training Workshop

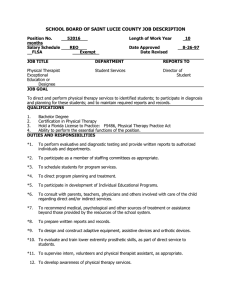

advertisement