When Will We Ever Learn? Recommendations to Improve Social Development

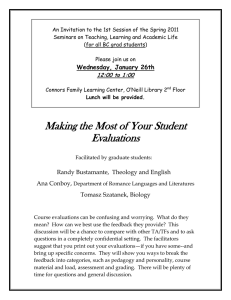

advertisement