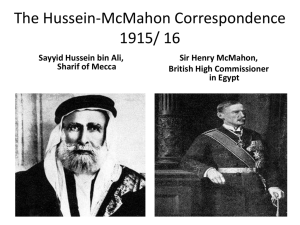

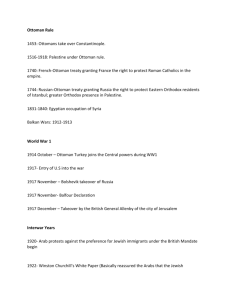

q. Title: This study traces British government policies with

advertisement