Down syndrome: good practice guidelines for education

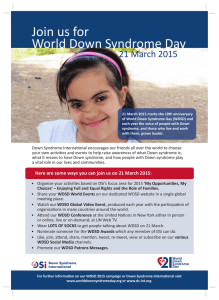

advertisement