WOMEN WHO MURDER IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND, 1558-‐1700 University ID: 0956526 September 2010

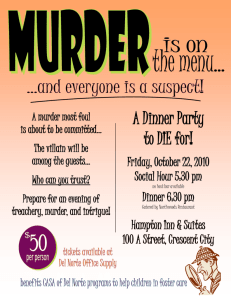

advertisement