Document 13605921

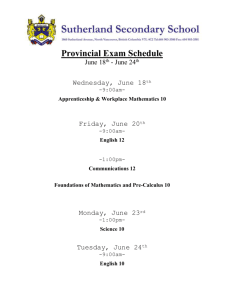

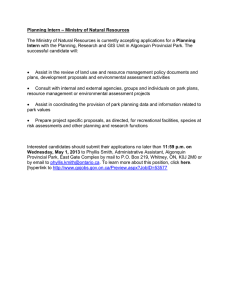

advertisement