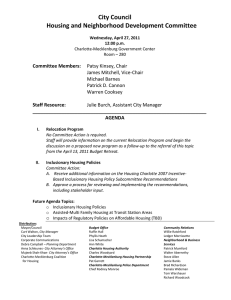

318 H S

advertisement