Discussant’s Notes on John J. Wallis’s Paper:

Discussant’s Notes on John J. Wallis’s Paper:

Did the New Deal Save Democracy and Capitalism?

Implications for the 21 st

Century

Professor Wallis’s paper ranges over economic, social, political and international history in exploring how the New Deal made the modern world less unstable. His argument, as I understand it, is that the New Deal made it politically acceptable for governments in Washington to co-ordinate responses to economic crises. Since the

1940s American governments have extended the New Deal model to the wider world, making possible international responses to crises. As a result, the great recession of

2008 has not (so far) become a great depression on the scale of the 1930s.

Unlike many historians, Professor Wallis offers an explicit counterfactual in relation to the spread of the New Deal model: what would have happened had

American attitudes to the wider world remained as they were in the days of Woodrow

Wilson? The implied answer is that the world would have been deprived of American leadership. The domestic counterpart to this counterfactual is: what would have happened if the New Deal had not established that Federal expenditure would be guided (largely?) by impersonal rules rather than patronage. Professor Wallis suggests that, in the absence of such rules, the Federal government’s freedom of action would have been constrained by Congress, with the result that there would have been no effective co-ordinator of responses to economic crises.

Americans have a wise saying that what one sees depends on where one sits.

In order to offer a different perspective from that of an American historian, I shall begin by quoting the comments of a Treasury official arguing in 1935 that Britain should not follow the example of the New Deal. He wrote: ‘In the United States

2 gambling holds much the same place in national life as cricket does in ours. Nothing, therefore, is more natural than that the American government should indulge in a gamble while a British government has to keep a straight bat and sometimes to stone wall.’

1

Of course, by using the word ‘gamble’ the Treasury official was being needlessly offensive, as Treasury officials are wont to be, but even if one substitutes

William Barber’s more judicious comment that Roosevelt engaged in ‘bold experimentation’, one is left with an impression of policy U-turns and political opportunism.

2

As Professor Wallis notes, there was more than one phase to the New

Deal; recovery was incomplete in 1937; and there was the Roosevelt recession of

1938. From the spring of 1938 Roosevelt was converted to the idea of a fiscal stimulus of loan-financed public works, but the effects of this quasi-Keynesian policy are hard to disentangle from the effects of the Second World War, since large Allied orders for munitions and other goods were placed in America from the autumn of

1939. This raises the question of whether one can talk unambiguously about the economic effects of the New Deal. Could the United States have avoided economic recovery between 1939 and 1945?

A second question, also arising from the Treasury official’s comments, is: was the New Deal the only solution to the depression? Neville Chamberlain, as

Chancellor of the Exchequer, stonewalled over loan-financed public works, and instead pursued a consistent policy based on moderate tariffs, imperial preference, a floating exchange rate and, particularly, low interest rates. The recovery he presided over between 1932 and 1937 was more complete than that achieved by Roosevelt

(unemployment halved in Britain between these dates). Of course a general tariff

1

Memorandum by Sir Frederick Leith-Ross, in Treasury papers, series 188, file 117, National

Archives of the UK: Public Record Office.

2

William J. Barber, Design within Disorder: Franklyn D. Roosevelt, the Economists and the

Shaping of American Economic Policy, 1933-1945 (CUP, 1996), p. 23.

3 brought once-and-for-all benefits to a hitherto free-trade nation that were not available to the protectionist United States, and imperial preference was a peculiarly British trade policy. Nevertheless, could a consistent, ‘straight-bat’ approach based on a floating exchange rate and low interest rates have worked for the United States as well as for Britain? Was Roosevelt’s New Deal the only approach to economic recovery?

Professor Wallis’s emphasises the social and political aspects of the New Deal.

We are left to wonder why the United States was so far behind countries like

Germany and Britain in developing social insurance. Stress is placed on rules required to ensure impersonality in the implementation of policy, but I wonder if something could be said about the lack of a national bureaucracy appointed impersonally though public examination? Was the United States in 1933 backward in terms of Samuel Huntington’s concept of modernity compared with Germany and

Britain? Mention of Germany in 1933 reminds one that modernity may have many aspects.

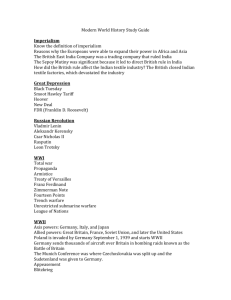

Turning to the statistics of Federal expenditure (Figure 1 and Table 2), I wonder if what we are observing here is a similar displacement effect to that noted by

Peacock and Wiseman in relation to the effects of war on public expenditure in

Britain. According to Peacock and Wiseman, once taxes have been raised for temporary military purposes, part of the revenue can be diverted to welfare expenditure.

3

There also seems to have been a peace dividend in both the United

States and Britain as Cold War tensions eased in the 1960s. The pattern of the proportion of GDP devoted to welfare expenditure after 1945 being greater than before the war, and then of a rising proportion of GDP devoted to welfare expenditure from the 1960s being offset by a falling proportion devoted to military expenditure, is

3

Alan Peacock and Jack Wiseman, The Growth of Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom

(London: Allen and Unwin, 1967).

4 similar in both countries.

4

Is it possible that war was more important than the New

Deal in expanding and developing the role of the state? Even if that were so,

Professor Wallis’s thesis about the importance of the New Deal ideology could be defended since he is concerned with how the United States reacted to crises. I would only observe that it is generally agreed that the Second World War gave an impetus to the development of the British welfare state, and in that case the ideology was partly liberal (Beveridge and Keynes) and partly socialist (the Labour party).

With regard to the international aspects of Professor Wallis’s paper, I confess that I blinked when I read the words: ‘in the lead up to the Second World War, the US played the central role in organizing the Allied response to Germany’ (p. 4). Then I remembered that, whereas for Britons the war against Hitler began in September 1939, the date for America is December 1941. I accept that the influence conferred by Lend

Lease enabled the United States to take the lead in framing the post-war order through the Atlantic Charter and the Bretton Woods agreements. However, American dominance in 1945 reflected the fact that all other advanced industrial countries had been damaged by the war. Once these economies recovered, and once some countries, like Japan from the 1960s to the 1980s, or China more recently, experienced high economic growth, the world became multi-polar again. Is the New Deal a sufficient explanation of the extent of the willingness of most countries to co-operate in an economic crisis?

In raising that question, I do not doubt that the world has benefited from the existence of a problem-solving ideology based on co-ordination led from Washington.

But what has moved other countries to acquiesce in American leadership? In the case of Britain, willingness depended on a belief, articulated most clearly by Keynes, that

4

For British data see Roger Middleton, Government versus the Market: The Growth of the

Public Sector, Economic Management and British Economic Performance, c. 1890-1979

(Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1996), p. 91.

5 prosperity depended upon an expansion of international trade. Presumably a similar conviction motivates the nominally Communist Chinese government today.

Returning to American history, suppose we change the counterfactual? What would have happened if Hoover had won 1932 election? The United States had not been not wholly absent from international economic co-operation before 1933: for example, both the Dawes and Young plans to deal with reparations were named after

Americans. The Hoover moratorium was an imaginative response to the effect of falling prices on the fiscal burden of inter-governmental debts. A Republican administration could hardly have been less international in its approach to the Great

Depression than Roosevelt was in 1933-35. Would America have been led eventually by self interest to international collaboration regardless of its domestic politics?

I would like to end by saying how much I have enjoyed Professor Wallis’s paper. The questions I have raised are not intended to be destructive of his thesis, but rather to encourage more elucidation. To sum up:

1) Was the New Deal the only way in which to tackle the Great Depression?

2) Why was the new American approach to economic crises acceptable to other countries after 1945?

3) Do international economic policies depend upon domestic ideologies?

G. C. Peden

University of Stirling