Health belief model and its aplication to mammography screening in... wellness program

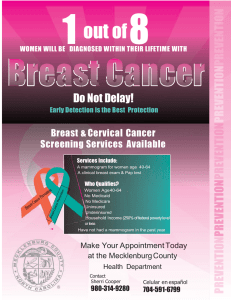

advertisement