A content analysis of commercially prepared thinking skills programs

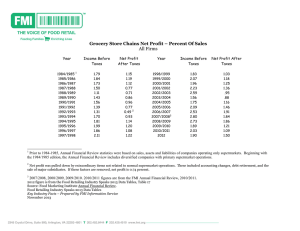

advertisement