Dimensions of health and rural resident's health care resources

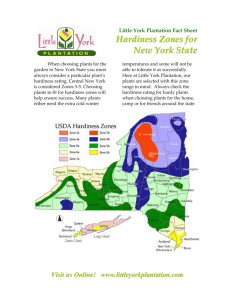

advertisement