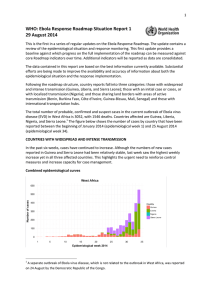

Assessing the socio-economic impacts of Ebola Virus Disease in Title

advertisement