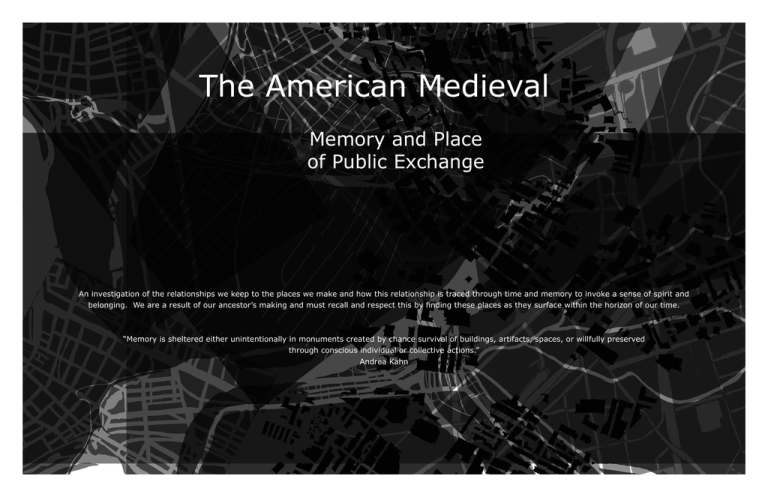

The American Medieval Memory and Place of Public Exchange

advertisement