THE HISTORICAL POWER OF THE IMAGINATION: By

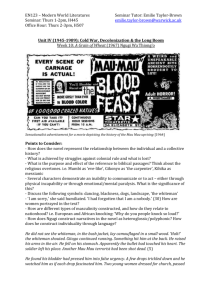

advertisement