Document 13447247

advertisement

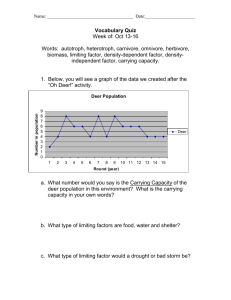

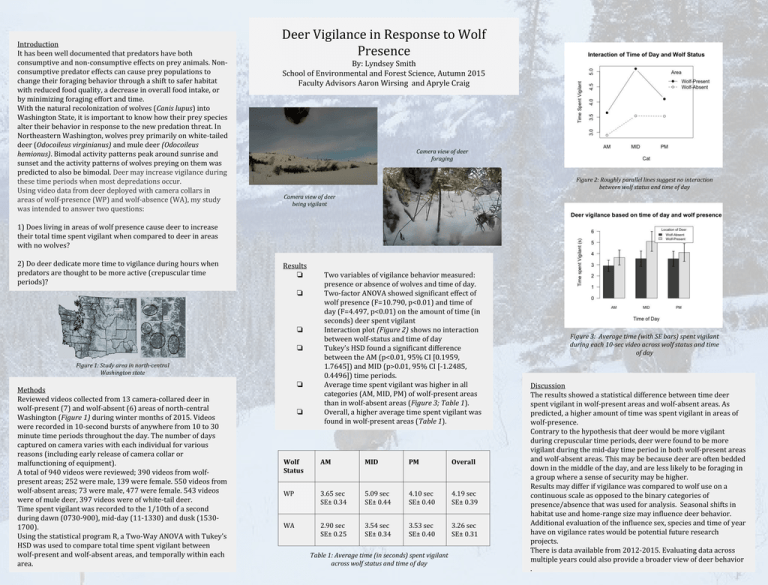

Introduction It has been well documented that predators have both consumptive and non-consumptive effects on prey animals. Nonconsumptive predator effects can cause prey populations to change their foraging behavior through a shift to safer habitat with reduced food quality, a decrease in overall food intake, or by minimizing foraging effort and time. With the natural recolonization of wolves (Canis lupus) into Washington State, it is important to know how their prey species alter their behavior in response to the new predation threat. In Northeastern Washington, wolves prey primarily on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). Bimodal activity patterns peak around sunrise and sunset and the activity patterns of wolves preying on them was predicted to also be bimodal. Deer may increase vigilance during these time periods when most depredations occur. Using video data from deer deployed with camera collars in areas of wolf-presence (WP) and wolf-absence (WA), my study was intended to answer two questions: Deer Vigilance in Response to Wolf Presence By: Lyndsey Smith School of Environmental and Forest Science, Autumn 2015 Faculty Advisors Aaron Wirsing and Apryle Craig Camera view of deer foraging Figure 2: Roughly parallel lines suggest no interaction between wolf status and time of day Camera view of deer being vigilant 1) Does living in areas of wolf presence cause deer to increase their total time spent vigilant when compared to deer in areas with no wolves? 2) Do deer dedicate more time to vigilance during hours when predators are thought to be more active (crepuscular time periods)? Results ❏ ❏ ❏ ❏ Figure 1: Study area in north-central Washington state Methods Reviewed videos collected from 13 camera-collared deer in wolf-present (7) and wolf-absent (6) areas of north-central Washington (Figure 1) during winter months of 2015. Videos were recorded in 10-second bursts of anywhere from 10 to 30 minute time periods throughout the day. The number of days captured on camera varies with each individual for various reasons (including early release of camera collar or malfunctioning of equipment). A total of 940 videos were reviewed; 390 videos from wolfpresent areas; 252 were male, 139 were female. 550 videos from wolf-absent areas; 73 were male, 477 were female. 543 videos were of mule deer, 397 videos were of white-tail deer. Time spent vigilant was recorded to the 1/10th of a second during dawn (0730-900), mid-day (11-1330) and dusk (15301700). Using the statistical program R, a Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD was used to compare total time spent vigilant between wolf-present and wolf-absent areas, and temporally within each area. ❏ ❏ Two variables of vigilance behavior measured: presence or absence of wolves and time of day. Two-factor ANOVA showed significant effect of wolf presence (F=10.790, p<0.01) and time of day (F=4.497, p<0.01) on the amount of time (in seconds) deer spent vigilant Interaction plot (Figure 2) shows no interaction between wolf-status and time of day Tukey’s HSD found a significant difference between the AM (p<0.01, 95% CI [0.1959, 1.7645]) and MID (p>0.01, 95% CI [-1.2485, 0.4496]) time periods. Average time spent vigilant was higher in all categories (AM, MID, PM) of wolf-present areas than in wolf-absent areas (Figure 3; Table 1). Overall, a higher average time spent vigilant was found in wolf-present areas (Table 1). Wolf Status AM MID PM Overall WP 3.65 sec SE± 0.34 5.09 sec SE± 0.44 4.10 sec SE± 0.40 4.19 sec SE± 0.39 WA 2.90 sec SE± 0.25 3.54 sec SE± 0.34 3.53 sec SE± 0.40 3.26 sec SE± 0.31 Table 1: Average time (in seconds) spent vigilant across wolf status and time of day Figure 3: Average time (with SE bars) spent vigilant during each 10-sec video across wolf status and time of day Discussion The results showed a statistical difference between time deer spent vigilant in wolf-present areas and wolf-absent areas. As predicted, a higher amount of time was spent vigilant in areas of wolf-presence. Contrary to the hypothesis that deer would be more vigilant during crepuscular time periods, deer were found to be more vigilant during the mid-day time period in both wolf-present areas and wolf-absent areas. This may be because deer are often bedded down in the middle of the day, and are less likely to be foraging in a group where a sense of security may be higher. Results may differ if vigilance was compared to wolf use on a continuous scale as opposed to the binary categories of presence/absence that was used for analysis. Seasonal shifts in habitat use and home-range size may influence deer behavior. Additional evaluation of the influence sex, species and time of year have on vigilance rates would be potential future research projects. There is data available from 2012-2015. Evaluating data across multiple years could also provide a broader view of deer behavior .