“Moral responsibility”: a Case Study in the Biology of Ethical Language

advertisement

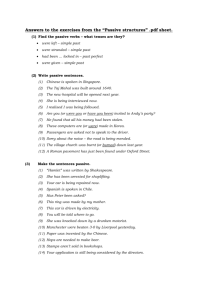

“Moral responsibility”: a Case Study in the Biology of Ethical Language R.E. Jennings jennings@sfu.ca C. Verbauwhede cverbauw@sfu.ca The Biology of Language in General Language is primarily1 a physical, more particularly a biological, phenomenon. It consists of physical occurrences (speech, gesture, inscription, and so on) that have physical effects (neural, oral, gestural, motional and so on). To notice that the effects of linguistic occurrences are conventional is, from a biological point of view, to notice that the causal significance of particular linguistic events has itself a causal history. Since the causal significance of linguistic events depends upon mediating neural effects, when those effects are typed, the types will therefore constitute species, where by a species is understood a union of populations temporally ordered by an engendering relation. In practical terms, the causal significance of present speech is engendered by the causal significance of previous speech. But these species have in common with biological species that they constitute non-classical sets, for if we consider the closure of a species under the engendered-by relation, we will find all ancestral species. Again, in practical terms, every member of a biological species has ancestors that are members of ancestral species. In the case of linguistic species, elements of language have the effects they do because of the ancestral effects of ancestral elements together with the nature of the engendering relationship. Since we have non-linguistic ancestors, all linguistic effects have ancestors that are non-linguistic effects. The apparent arbitrariness of linguistic effects is an early evolved characteristic, since, we may assume, the distant, non-linguistic ancestors of those effect-types were nonarbitrary. The task of the biologist of language is to say what can be said about language within this theoretical arrangement of parts. Within this theoretical framework, there is room for what might be called a philosophical2 biology of language. The physical facts of language impose empirical constraints upon what can be claimed by philosophical theory, and may ultimately explain the nature of philosophical difficulty itself. We do not venture much in defence of the second of these claims, but some inkling may be got from considering one fact about the relevant engendering relation. Since language is transmitted to children, linguistic species themselves admit of the language of ontogeny as well as that of phylogeny. Neural and other effects of language in individual adults develop from the effects of language in individual infants. There is no precise semantic audit of these effects in adolescence. The result is that genetic drift alone can go a long way toward explaining the comparative shortlivedness of the eco-systems of types that constitute whole languages. But it also 1 explains why for some elements of language, we should eventually find ourselves at such a loss to give an account of their “meaning” that we find ourselves talking for no reason other than to find out what we are talking about. And it may ground a prognosis for the likely success of the exercise. In this offering we illustrate one comparatively superficial respect in which the biology of language provides a criterion of adequacy for philosophical theory. This is the constraint, biologically imposed, that any claim about current use of vocabulary must in principle be supportable by an account of how that use was engendered by ancestral use. An upshot is that the plausibility of any claim about current use must depend upon the plausibility of the theoretically implicit3 claim that such a use was engendered by known previous uses. The Case: moral responsibility Some recent speculation about the nature of moral responsibility provides a case in point. It provides an occasion for us to set side by side the biological method and the method that seeks what has been called “reflective equilibrium,” in which sets of intuitions are checked for logical consistency with one another and with competitor sets. Within the limitations of the previous section, the two methods are not in conflict, and we offer no final judgement between them. Our largest methodological claim is that the equilibrium practitioners might find useful restraints in the standards of empirical plausibility that the historical philology provides. All ethical vocabulary is ethicalized vocabulary. That is, it is vocabulary that originally had non-ethical uses, in many cases religious or legal in character. Responsibility is a case in point.Responsibility is constructed from the Latin root respons- and the suffix -bilem. Respons-, in turn, results from the combination of the prefix re- with the verb spond re, which we translate as ‘to make a solemn pledge.’ The resulting compound, respond o found use in contractual settings in which an engagement was reciprocated (Ernout4, s.v.). In Latin, the root verb was applied to pledges of a religious nature, in particular ones in which the father promised (spondet) his daughter (sp nsa) to the bridegroom (sp nsus—a word that survived into Middle English) (Ibid.). Our word spouse is a derivative of these uses, as is sponsor, for which the ecclesiastical use retains the old meaning: “one who answers [is liable] for an infant at baptism” (OED, s.v.). With the re- prefix attached, respond o was initially applied to oracles, whose predictions were made only after a pledge was received. This use conserved the legal and religious applications of the root in the word resp nsum (Ernout, s.v.). R sp nd re subsequently lost its technical flavour and came to be used as “answer” or “respond” in the common language (Ibid.). The historical connection between answerable and responsible is easy to understand when one pays attention to the Old English roots of answer. Similarly constructed, it results from combining the prefix and-, “against” or “in reply,” with the root “swaru,” from the verb sw rian, “to swear.” 2 The suffix, -bilem requires separate mention. It was attached to verbs to form adjectives in Latin with the sense “able to be,” or “fit to.” Adjectives of the former were passive, as in vincibilis, “able to be overcome,” while those of the latter were active, as in stabilis, “fit to stand.” In later exploitations of Latinate formations, accordingly, words in -ble could therefore have either passive or active application, and in some cases both. Like the -able of answerable, the -ible of responsible is historically an active -ble construction. When one is responsible to or answerable to a person or a group of people—be it a supervisor, a board, a court or a nation— for one’s actions, one is able to answer to that group for5 something one has done. So far the constructions are grammatically active, but modally weak, that is, akin to possible rather than necessary. Historically, the language of responsibility was given its apparent force of requirement by the contingent fact that in any particular legal setting, the capability of answering defined a small or unit class. The requirement devolved, in the simplest case, upon the uniquely able. To be answerable or responsible for another was ancestrally to be in such a relationship to another as to be compellable to answer for his or her acts, where, once again the compulsion devolved. The only known cases, historically, in which either word was used as a passive was in application to questions or reasons, but these uses are comparatively rare and, in the case of responsible, now obsolete: 1697 J. Collier Ess. Mor. Subj. (L.) His best reasons are answerable; his worst are not worthy of being answered. and 1647 Lilly Chr. Astrol. lviii. 383 This is a difficult Question, and yet by Astrologie responsible. Now some passive adjectives in -ble acquire additionally restrictive uses according to the salient reference of the component verb. Thus Mill’s well-know paradigm, audible acquires restrictive uses accordingly as the auditory capacities of the speaker, or members of his set, or his species, or normal such members are understood. As Mill suggests6, the proof that a sound is audible lies in the fact that a person with sufficiently good hearing would be able to perceive it. In the case of desirable, the originating restriction is social: in questioning a property’s desirability, we want to know whether it is to be desired by the appropriate class of person—one with good taste or intent or character, say—not by just anyone. Though it is easy to see that the passive respectable is socially restricted, it is less obvious, but true, that a similar restriction historically originated noble. Noble descends from the Latin construction (g)n bilis (“(k)no(wa)ble”), a passive use of bilis which designates the person as one worthy of being known; that is, a person one can know without social inconvenience or mishap. Conversely, an ignoble person, had the originating use persisted, would be one who could not be acknowledged without social cost. It is the trappings of the restrictive conditions that enables the simplification of the constructions through ellipsis of the by phrase. 3 By their trappings, the respectable, the noble, the ignoble were recognizable independently of the social relationships that originally conferred the properties. In these cases the early straitened reference set becomes broadened in later uses, eventually so broadened as to be indefinite in the one case and absent in the other. In the case of responsible, the ethicalized uses apply the word to cases in which responsibility is to a body having no legal, but only social powers of compulsion. The construction responsible to loses its to in later constructions because the grammatical object of the preposition becomes so diffuse as to be constant albeit vaguely so, and in the course of successive transmissions completely forgotten. In early applications, one is always responsible to a particular other; in later ones, one can be said to be a responsible person. With the historical ties of these later uses reconstructed, we can perhaps say that a responsible person is one able to answer to anyone who bothers to ask, for anything he or she undertakes. We may contrast active responsible with passive respectable by noting that the ellipsis in the one case sheds a to completion, in the other a by completion. And of course in the case of respectable, noble, ignoble and so on, the nature of the implicit reference is not entirely lost, but retained in the derivative element of desert or worthiness (unworthiness). Now we do not suggest that there is nothing more to be said, historically or otherwise about responsible. Nothing we have said would enable one to predict such later uses as the following: “To have a companion animal at home is really new in many cities in China, and many owners of pets, they do not understand how to be responsible, what is their responsibility to these dogs and cats,” said Aster Zhang, a director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare. (The Vancouver Sun, 2003-05-07.) On Tuesday, B.C. conservation officers continued to comb the area looking for the bear responsible. They have killed one bear already, but [RCMP Staff Sergeant Bryan] Reid said they weren’t certain it was the right bear. “The bear responsible for this attack was clearly aggressive and predatory in nature,” Reid said. “The fact that it returned twice indicates it’s clearly a problem.” (The Vancouver Sun, 2002-09-04.) “I would have thought he had some sense of responsibility. It could be that I’m wrong and he doesn’t feel any sense of responsibility to tell people what he stands for given that he has already sown up the election and has millions of dollars in the bank for his campaign,” said Layton. (The Vancouver Sun, 2003-07-02) Nor would it, of itself explain such later constructions as responsible (irresponsible) actions behaviour and so on. However, we do maintain that the main lines of the ethical uses of responsible are sufficiently explained by the historical developments that we have sketched, and that no other historical developments are required. We accept that this does not provide a semantic account: the biological approach is 4 inimical to the notion that a semantic account must be available, as it is to the notion that one is necessary for understanding. Rather our claim is that any purported semantic account would have to accord with the developments that we have outlined. All that would defeat this claim would be a more highly confirmed historical account, not an incompatible semantic theory. Once the historical developments are understood, anyone advancing a semantic theory not in accord with them must resort to a not-particularly-scientific creationism, casting himself in the role of creator. And to be sure, a sufficiently influential semantic creator might bring about a semantic cult even outside the academy, and ultimately a new use. There are many examples of such triumphs of fiat over est. Consider as a live case, David Copp’s proposal ‘that in a broad sense, moral responsibility for an action is a matter of deserving a moral response on the basis of the action7. In advancing this proposal, Copp takes himself to be following Strawson. One might say that Copp has rather overtaken Strawson and even Fisher and Ravizza in the boldness of his restatement. Strawson’s essay8 can be seen as an attempt to describe an affective/reactive substrate of moral discourse. For the formal semanticist venturing into the literature of ethics for the first time, Strawson’s essay is like an exposition of subatomic phenomena in order to render reasonable the peculiar behaviour of connectives in quantum logic. It attempts to describe the human landscape in which moral discourse gains its peculiar traction. But any role that particular moral vocabulary plays there is a product of historical linguistic development. No feature of moral discourse is in principle inexplicable, given access to antecedent features and broader understanding of language. In the case of Copp’s purportedly passive responsibility, we lack even the grounds for a rudimentary explanatory theory, since no actual historical uses have existed to engender it. Had there ever been any relevant passive use of responsible, there might be an historically traceable genealogy of a response-worthiness use of responsible. We might, for example, be able to give an account roughly parallel to that of Mill’s desirable. It might be (to reissue Copp’s own coinage) ‘not clear how to specify it in a clear way’. But the reasons would be bio-linguistic ones. In fact the difficulty of the exercise is at root a bio-linguistic one. The processes by which species of linguistic effects evolve is such as to put much of our vocabulary, ethical and nonethical, beyond the event-horizon of any but simple-hearted semantic theory. Because the only resources available for semantic accounts involve other equally problematic vocabulary (worthy, deserving, intentional and so on), semantics gives way to conceptual geography (whatever, in the circumstances, concepts could be). The possibilities for understanding left to us lie in particular explanatory theories within an overarching biological understanding of the nature of language. Laboratory for Logic and Experimental Philosophy Simon Fraser University URL: www.sfu.ca\llep 5 SOURCES OF EXAMPLES 1697 Jeremy Collier _Essays Upon Several Moral Subjects_ 1647 William Lilly _Christian Astrology_ 6 APPENDIX ACTIVE AND PASSIVE ADJECTIVES IN –BLE ACTIVE Capable Conformable Durable Equable Equitable Horrible Perishable Responsible Sociable Stable Suitable 7 PASSIVE Audible Credible Debatable Flexible ACTIVE AND PASSIVE Agreeable Amiable Answerable Changeable Comfortable Companionable Flexible Knowledgeable Moveable Passable Reasonable Risible 8 Gullible Noble Insuffer Invincib Respect Suscept Get-at-a 9