24.961 Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness

advertisement

24.961 Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness

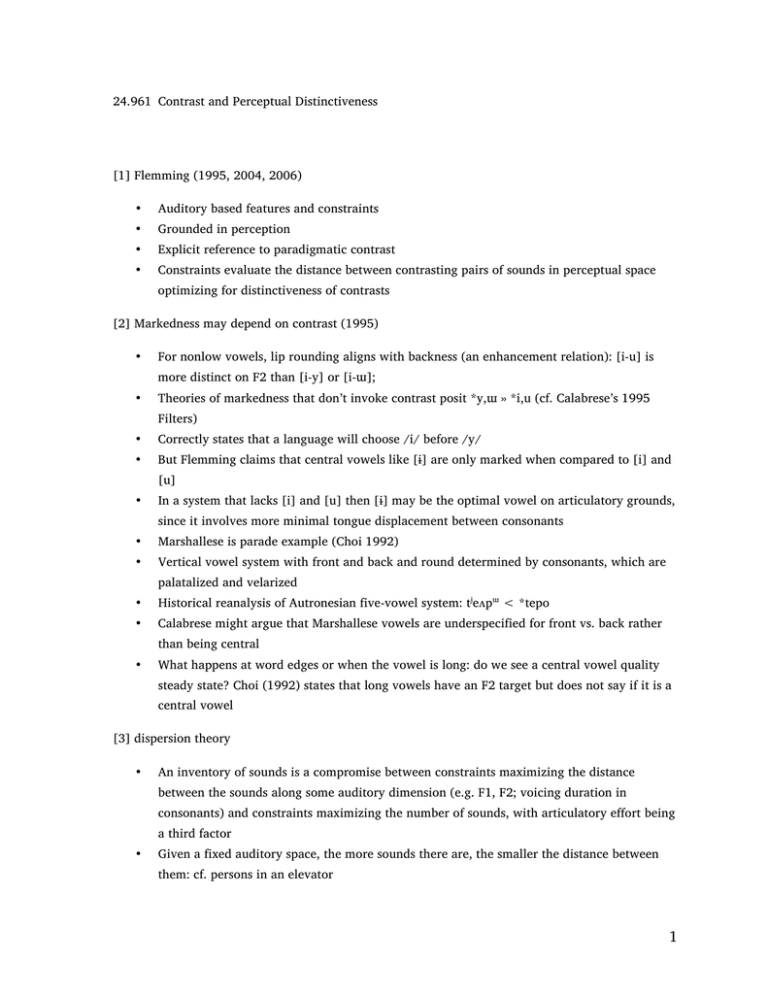

[1] Flemming (1995, 2004, 2006)

•

Auditory based features and constraints

•

Grounded in perception

•

Explicit reference to paradigmatic contrast

•

Constraints evaluate the distance between contrasting pairs of sounds in perceptual space

optimizing for distinctiveness of contrasts

[2] Markedness may depend on contrast (1995)

•

For nonlow vowels, lip rounding aligns with backness (an enhancement relation): [i-u] is

more distinct on F2 than [i-y] or [i-ɯ];

•

Theories of markedness that don’t invoke contrast posit *y,ɯ » *i,u (cf. Calabrese’s 1995

Filters)

•

Correctly states that a language will choose /i/ before /y/

•

But Flemming claims that central vowels like [i] are only marked when compared to [i] and

[u]

•

In a system that lacks [i] and [u] then [i] may be the optimal vowel on articulatory grounds,

since it involves more minimal tongue displacement between consonants

•

Marshallese is parade example (Choi 1992)

•

Vertical vowel system with front and back and round determined by consonants, which are

palatalized and velarized

•

Historical reanalysis of Autronesian five-vowel system: tjeʌpɯ < *tepo

•

Calabrese might argue that Marshallese vowels are underspecified for front vs. back rather

than being central

•

What happens at word edges or when the vowel is long: do we see a central vowel quality

steady state? Choi (1992) states that long vowels have an F2 target but does not say if it is a

central vowel

[3] dispersion theory

•

An inventory of sounds is a compromise between constraints maximizing the distance

between the sounds along some auditory dimension (e.g. F1, F2; voicing duration in

consonants) and constraints maximizing the number of sounds, with articulatory effort being

a third factor

•

Given a fixed auditory space, the more sounds there are, the smaller the distance between

them: cf. persons in an elevator

1

!

Sound are located in a multi-dimensional perceptual space where perceptual

Forsavow

asssum

somceoul

grd

idbe

with

idieeadlizteodm

spoarceet;ha

F2nin

barckesl;l.F1 doubles bark frequencies

e•s, the

me eIlPs A

ymebol

appl

one

a ranked set of

een contrasting sounds.

ints are opposed by two

general (families of) constraints:

Minare

aD

xiism

ze t1he

beVowels

rt-of

astspecified

. ist-F2:3by

! Perceptual dimensions

n-ary

features.

feature

matrices: [F1

• ! *M

t-iF2:

» *num

MinDis

F2:c2ont

» are

*rMi

nsD

» ....

» *MinDist-F2:6:

this 1,

markedness

!

M

ini

m

i

z

e

a

r

ti

c

ul

a

t

or

y

e

f

fort.

F2 6, …].

hierarchy optimizes the distance between sounds along some auditory dimension

Ma

numb

erbe

ofrcof

ontcront

astsra(v

• Ma

xixmimi

izezethe

num

stosw. els): more information can be stored and transmitted per

uni

t ofesspa

ce tor

timnc

e, ybut

t tIhe

aterapos

sibl

!O

ppos

the

ende

of aM

NDcIos

STt of

to gfarevor

few

meacxionf

mauslliyondistinct contrasts.

• Sound inventories arise from embedding Maximize Contrasts somewhere within the MinDist

! With more contrasting sounds, each sound spoken can distinguish more words (and thus

nkinys

g more information).

onve

cra

• ! IEr

taebl

w: de

reas

e eac

Min

distts=

onest

mrplateaminent

deabe

s alopos

iticve

cons

trahint

tha

elFe2ctval

s tuhee blayrge

3

Japran

r nt

Kor

• not

Firsbe

t tabl

elghe

e, sdeccon

d tfroai

en eealiumfor

inaftievde-vow

by hi

-raesnke

ons

s)ean

.

inventory of contrasts (that has

Flemming, Edward. “Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness.” In The Phonetic Bases of Markedness. Edited by Bruce Hayes,

! Kirchner,

INDIST

Robert

and Donca Steriade. Cambridge University Press, 2004. © Cambridge University Press. This content is

excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

M

constraints impose the preference for contrasts between front unrounded and

back rounded vowels.

! If there is no F2 contrast then these constraints are irrelevant (cf. vertical vowel

2

inventories).

16. Differences on multiple dimensions can combine to contribute to the overall distinctiveness

•

Candidate d is winner in second tableau; by moving Max Contrasts up (leftward) in the

MinDist hierarchy, we derive more vowels but at the cost of closer spacing; by moving down

(rightward) we derive fewer vowels but with larger spacing

•

Korean has /i/ vs. /ɨ/ vs. /u/ while Japanese has /i/ vs. /u/ (though /u/ is phonetically

quite front, at least in Tokyo dialect; if it really is /ɯ/ then we would have to appeal to

articulatory effort to choose /ɯ/ over the auditorily more optimal /u/. One the other hand,

phonologically Jap /u/ patterns with labials, causing /h/ to be realized as [ɸ]). Perhaps F3 is

relevant; see discussion of Cantonese below.

Vowel height (F1)

•

Standard Italian (i,u, e,o,ɛ,ɔ,a) arises from ranking MinDist F1:2 » Max Contr » MinDistF1:3

Flemming, Edward. “Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness.” In The Phonetic Bases of Markedness. Edited by Bruce Hayes,

Robert Kirchner, and Donca Steriade. Cambridge University Press, 2004. © Cambridge University Press. This content is

excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

•

Spanish demotes Max Contrast for greater dispersion: MinDist F1:3 » Max Contr »

MinDistF1:4

Flemming, Edward. “Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness.” In The Phonetic Bases of Markedness. Edited by Bruce Hayes,

Robert Kirchner, and Donca Steriade. Cambridge University Press, 2004. © Cambridge University Press. This content is

excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

•

Arabic {i,u,a}

Flemming, Edward. “Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness.” In The Phonetic Bases of Markedness. Edited by Bruce Hayes,

Robert Kirchner, and Donca Steriade. Cambridge University Press, 2004. © Cambridge University Press. This content is

excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

[4] neutralization of contrasts

•

In unstressed syllables Standard Italian seven vowels reduce to five, with loss of the

distinction between open and closed mid vowels

3

•

EF sees this as a response to increased artic effort that would be required to realize vowels in

shorter time span of unstressed syllables

•

Chief evidence is that low vowel /a/ is raised to [ɐ]; this encroaches on the vowel space; if

the same Min-Dist and Artic effort constraints that define the stressed vowel/lexical

inventory are imposed, then the number of distinctions decreases since the grammar now

chooses the five-vowel system

Flemming, Edward. “Contrast and Perceptual Distinctiveness.” In The Phonetic Bases of Markedness. Edited by Bruce Hayes,

Robert Kirchner, and Donca Steriade. Cambridge University Press, 2004. © Cambridge University Press. This content is

excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

Flemming, Edward. “The Role of Distinctiveness Constraints in Phonology.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

2006. © Edward Flemming. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license.

For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

[5] Dispersion and enhancement (Flemming 2006)

•

If dispersion constraints can freely interact with faithfulness and markedness constraints

then the model over-generates: the inventory of contrasting segments should vary with

context and targeted enhancement repairs should be able to rescue contrasts that are

challenged by context (e.g. adding a schwa to final voiced obstruents). Another problem is

an infinite regress: “the wellformedness of a candidate word [pad] might depend on whether

or not [pat] is a possible word. But to determine whether [pat] is a possible word, we have

to determine whether or not is statisfies MinDist constraints, requiring it to be adequately

distinct from its neighbors, and so on”.

•

EF’s claim is that we don’t in general find these effects and the only response to a

nonoptimal contrast is neutralization: in unstressed syllables distinctions are lost and the set

of vowels shrinks rather than shifts (e.g. by introducing length); the only response to final

voiced obstruents is devoicing (loss of contrast towards articulatorily less effortful sound)

•

Proposal is to restrict the role of dispersion constraints to defining the phonemic inventory

that encodes the lexicon and as a final “quality check” on the output of the input-output

mapping in the ESC (Evaluation of Surface Contrast) module; in particular, dispersion

constraints cannot interact with (be ranked with) the markedness and faithfulness

constraints that define the input-output mapping.

4

•

In the ECS there are (apparently) just the MindDist constraints and a general *Merger

constraint

[6]

Example from Cantonese:

high vowels:

i y

u

UG space:

F2

F3

5

4

3

2

1

i

y

ɨ

ʉ

u

4

3

2

1

i

ɨ

y,u

ɹ

constraint ranking for inventory

MINDIST=

F2:2

or F3:2

(14)

a.

i

!

b. ! i y

c.

iy !

d.

iy "

e.

i

u

u

u

u

u

*!

*!

MAXIMIZE

CONTRASTS

!!!

!!!

!!!!

!!!!

!!!

MINDIST=

F2:3

or F3:3

**!

*

***

***

MINDIST=

F2:4

**

**

*****

*****

Flemming, Edward. “The Role of Distinctiveness Constraints in Phonology.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

2006. © Edward Flemming. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license.

For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

Given an inventory of contrasting segments, the goal is to realize the full inventory of

contrasts in all contexts. So possible underlying forms consist of all sequences of segments from

• front rounded vowels found after dentals and velars but not labials: ti, tu, ty; ki, ku, ky but

the inventory and the goal is to realize these underlying forms faithfully. In some cases

pi, pu, contrasts

*py

underlying

are neutralized because they cannot be realized with sufficient

• could be repaired

by shift to

a new phoneme

-> pɨ) but this

is in general

not found;

distinctiveness

in a particular

context,

as in final(/py/

neutralization

of obstruent

voicing

contrasts.

Following

Flemming

only merger

to [i] (2002), we will analyze the restriction on front rounded vowels in

β

Cantonese

in

similar

terms. Coarticulation

with anofadjacent

labial

renders

[i] too[isimilar

to front

] that is

• in input-output mapping

there is coarticulation

/i/ with /p/

creating

a vowel

rounded

[y], so the contrast is neutralized in this context. In both cases the evaluation of

too close to /y/ and the response is to neutralize the [iB] - [y] contrast; the outcome is

distinctiveness must apply to the surface realizations of the contrasts in order to take contextual

determined by lowering ranking dispersion constraint maximizing distance from [u] and

effects

such as labial coarticulation into account. However, MINDIST and MAXIMIZE CONTRASTS

[i] freely with contextual markedness constraints if we are to account for the

must choosing

not interact

(17) Realization:

relative stability/pin/of inventories*Lacross

contexts.

these two generalizations motivates

ABIAL

IDENT(F2)

IReconciling

DENT(F3)

COARTICULATION

the distinctiona. between Realization

and

Evaluation

of

Surface

Contrasts (ESC). The Realization

*!

pin

*

b.

component maps

an input

string

onto

its

phonetic

realization

while

the ESC assesses the

!

pi n

**!

***

c.

p" n

distinctiveness of contrasts based on these phonetic realizations. The Realization component

incorporates(18)theESC:

contextual markedness constraints that motivate contextual variation in the

MINDIST=

*MERGE

MINDIST=

MINDIST=

/pyn , pin , pun /

F2:2 not include MF2:3

F2:4

realization of contrasts but does

INDIST constraints.

The MINDIST constraints

or F3:2

or F3:3

evaluate the outputs

in

ESC

but

cannot

directly

influence

the realization of a given

pin ,Realization

pun /

/pyn ,of

a.

*!

*

**

pyn pi n pun

input.

!

/pin , pun /

b.

*

pun model to neutralization of front rounding contrasts is illustrated by

piof

n this

The application

/pyn , pun /

c. (15) and (16). It is easier

* to se ethe overall

*! structure of the analysis by

the tableaux in

pyn pun

considering

ESC first

andofthen

turn to the

detailsin of

Realization.

Flemming, Edward.

“The Role

Distinctiveness

Constraints

Phonology.”

Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

2006.

©

Edward

Flemming.

All

rights

reserved.

This

content

is

excluded

from

Commons

license.

The ESC

the same ranking of of

MINDIST

constraints asittheis

Inventory

– there our

is no

re-consider

To evaluate

theemploys

distinctiveness

contrasts

necessary

toCreative

a target

input in

For more information,

see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

ranking of constraints

between components, although only certain classes of constraints apply in

relation to aeach

setcomponent.

of minimally

contrasting

inputs.

This

setplace

must

also occupies

the same

in the at least contain all input forms that

The initial hypothesis

is that *MERGE

ranking as MAXIMIZE CONTRASTS. This implies that the minimum level of distinctiveness that is

differ from the

target

by changing,

inserting

deleting

a single

5

acceptable

for a contrast

in the inventory should

also be theor

threshold

below which

a surface segment, but generally must

contrast is neutralized.

In

thewill

analysisbe

above,

the smallest acceptable

F3 contrast

must have

a

contain additional

forms

as

discussed

further

below.

Here

we

are

interested

in

the

input

distinctiveness of F3:2 since MINDIST = F3:2 ranks just above MAXIMIZE CONTRASTS (14). If

*M

ERGE occupies

the samevowel

position as adjacent

MAXIMIZE CONTRASTS

the rankingThe

of MINDIST

/pyn/ with aconstraints,

front

rounded

to a inlabial.

contrast set for this input includes

any contextual influence that would reduce the distinctiveness of an F3 contrast

!

!

1

2

3

1

!

2

1

3

2

!

1,2

1,2

1,2

1,2

3

3

3

3

3

Gallagher (2010)

•

two types of cross-linguistic root co-occurrence constraints on laryngeally marked

consonants such as ejectives

•

dissimilatory: C’VCV, CVC’V, CVCV, *C’VC’V (cf. Lyman’s Law in Japanese)

•

assimilatory (less common): *C’VCV, CVC’V, CVCV, *C’VC’V (Chaha)

•

Repair of dissimilation eliminates second ejective; repair of assimilation eliminates C’VC by

distributing

ejection through the root

436 Gillian

Gallagher

pattern

I call ‘mixed ’,*T’-K’

heterorganic

and homorganic

pairs pattern differT-K

(1) a. dissimilation

T’-K

ently. ‘ T-K’ stands for

any

pair

of

heterorganic

consonants,

while ‘T-T’

T-T

*T’-T’

T’-T

stands

for

any

pair

of

homorganic

consonants;

the

apostrophe

here stands

T-K

b. assimilation

T’-K’

*T’-K

or

implosive.

T-T

T’-T’

*T’-T

T-K

c. mixed

*T’-K’

T’-K

Gillian

Gallagher

a. Shus

wap: kw’alt

‘to stagger’

qet’ ‘to hoist’ kwup ‘to push’ qmut ‘hat

The constraints

b. Chaha: ji-t’ək’ir

‘he hides’

ji-kəft

‘he opens

*C’VC or CVC’

co-occurrenceT’-T’

restrictions

reflect

asymmetries

in the perceptual

T-T

*T’-T

Gallagher, Gillian. “Perceptual

Distinctness

and Long-Distance

Laryngeal Restrictions.” Phonology 27, no. 3 (2010),

strength

of contrasts

roots This

with

different

laryngeal

435-80.©

Cambridgebetween

University Press.

content

is excluded

from our configuraCreative Commons license. For more

Co-occurrence

restrictions

on reported

laryngealin features

have

various forms,

The experimental

results

w4 reveal

a three-tiered

hierhttp://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/

.

information,

see

Gillian

Gallagher

whichinat

glance distinctness

seem to be of

contradictory.

Assimilatory

and

disperceptual

laryngeal contrasts

in pairs of

roots.

thefirst

• Not restrictions

a simple markedness

hierarc

since

what is ruled

one tof

ype is preferred in the

similatory

are opposites

– hy

what

is prohibited

inout

oneintype

The constraints

[k’ap’i-kapi]

> is required

[k’api-kapi]

> Mixed

[k’ap’i-k’api]

language

isrprecisely what

in another.

restriction lanothe

co-occurrence restrictions reflect asymmetries in the perceptual

guages

are

particularly

puzzling,

because

the

antagonistic

requirements

to

B([T’-K’]:[T-K])

B([T’-K]:[T-K])

B([T’-K’]:[T’-K])

• Gaof

llagcontrasts

her treats between

this as arroots

ising frwom

par

adigmlaryngeal

atic disperconfigurasion constraint over the permitted

ithadi

fferent

assimilate and dissimilate coexist in different corners of the same lanThe

results

reported

in

wo4n reveal a three-tiered hier454

le

xicexperimental

apuzzling

lGillian

root

tyGallagher

pes

wit

hsystemic

respect

to ejeis

ctiunderstandable

guage.

This

array

of

restrictions

if markedness

hierarchy

projects

two

constraints,

defined

in

distinctness

in the perceptual

ofmarkedness

laryngeal contrasts

in pairs

of roots.

constraints

evaluate

contrasts

between

sets

of

roots

in

a

language

of

corresponding

to

the

two

asymmetries

in

(15).

I

refer

the“di

con5.2alyTsis

heisconstraints

• An

supported by a speech perception task (“samto

e” instead

or

fferent”)

that finds it is more

individual

forms.

that

evaluate

laryngeal

contrasts

between

roots

as

laryngeal

dis[k’ap’i-kapi]

>

[k’api-kapi]

>

[k’ap’i-k’api]

Laryngeal

co-occurrence

eflect

inerthe

di

t to constraints.

judg

e apaper

C’ vs3.isCrestrictions

contrast

in trhe

preasymmetries

sence of anoth

ejeperceptual

ctive than when the

The

argument

this

that

laryngeal

co-occurrence

restrictions

ARDIST in

or

Lfficul

B([T’-K’]:[T-K])

B([T’-K]:[T-K])

B

([T’-K’]:[T’-K])

strength

of

contrasts

between

roots

with

di

ff

erent

laryngeal

configuraare a unified

andt is

areplain

best: i.e.

understood

accompphenomenon,

anying consonan

more errowhen

rs on the

C’VCperceptual

’ vs. C’VC than on CVC’ vs. CVC or

tions.

The experimental

w4 reveal

a three-tiered

a. LarDist(2v1)-[F]

properties

of laryngeal

contrasts results

betweenreported

roots arein

taken

into account.

The hierhierarchy

projects

two

systemic

markedness

constraints,

defined

in

C’

Vtw

C ovsin

CV

C perceptual

archy

the

distinctness

of

laryngeal

contrasts

i

n

pairs

If

c

on

tra

sting

root

s

each

have

an

[F

]

segm

ent,

then

th

ey

do

tof roots.

paper presents experimental support for a hierarchy of perceptual no

discorresponding

to

the

two

asymmetries

in

(15).

I

refer

to

the

conminimally

di‰er

in

[F].

tinctness

of laryngeal contrasts among roots, and develops an analysis of

•

that evaluate

laryngeal >

contrasts

between roots

dis(15)

[k’ap’i-kapi]

[k’api-kapi]

> as laryngeal

[k’ap’i-k’api]

laryngeal

co-occurrence

based on

markedness

Let

xR1,

yR1, xR2,restrictions

yR2 be segments

thatsystemic

can be specified

for conthe

D([T’-K’]:[T-K])

IST constraints.3

or LAR

B

B

([T’-K]:[T-K])

B

([T’-K’]:[T’-K])

straintslary

projected

from this

idea ising

that

laryngeal

ngeal feature

[F]. hierarchy.

Let R1 and The

R2 becentral

two contrast

roots,

such

• a. th

co-occurrence

restrictions

are

not

prohibitions

against

certain

configuraat

xR1,

yR1ŒR1

and

xR2,

yR2ŒR2

and

R1=R2,

except

that

LarDist

(2v1)-[F]

hierarchy

projects

two

systemic

markedness

constraints,

defined

in

≠

tions ofyThis

laryngeal

features,

but

rather

are

restrictions

on

the

perceptual

R1

y

R2

.

I

f

x

R1

an

d

xR2

ar

e

[F],

then

R

1

an

d

R

2

ca

nnot

di‰e

r

on

lyt

an [F] segmen

If twocorresponding

contrasting root

s the

eachtwo

have

t,(15).

thenIthey

dotono

(16),

to

asymmetries

in

refer

the

condistinctness

of contrasts

among

possible roots in a language. The operative

in

a single

instance

[F].

minimally

di‰er

inof

[F].

straints

that

evaluate

laryngeal contrasts

between roots

laryngeal disconstraints

in

laryngeal

co-occurrence

restrictions

not as

standard

•b. LarDist

(1v0)-[F]

Let xor

R1,LyAR

R1D

, xIST

R2,constraints.

yR2 be seg3ments

that can beare

specified

for the

tance

Optimality

(OT;

Prince

Smolensky

markedness

conIflaryn

twoTheory

ge roots

eac

have

tw

thtat

ma

y be

gcont

eal rastin

featur

[F].

L

ethR&

1 and

Ro2 segments

be two1993)

con

ras

ting

rospec

ots, ified

such

straints.for

Rather,

they

are

systemic

constraints

that

evaluate

the

marked[F],

then

they

do

not

minimally

di‰er

in

[F].

that a.xR1

, yR1ŒR1

and xR2, yR2ŒR2 and R1=R2, except that

(16)

LarDist

(2v1)-[F]

• of Le

ness

the

set

of

possible

language.

This

follows

t≠

xR1

,Ify. tw

R1

,tra

ycontrasts

bearrsoot

m

tsh thhave

at1 an

caann

b]e2 seg

sapproach

pnnot

em

ciefie

dthe

fo

rnon

tthhly

e y do not

yR1

yR2

If,oxxR1

dR2

xing

R2

eeg[in

Fs],ean

then

R

d[F

R

ca

di‰e

cR2

onan

st

ac

nt,

much previous work integrating systemic contrast markedness into

Gallagher, Gillian. “Perceptual Distinctness and Long-Distance Laryngeal Restrictions.” Phonology 27, no. 3 (2010),

phonological

theory,

including

Contrast

Preservation

Theory roots,

(Kubowicz

lainryngea

l feature

[Fdi‰er

].ofLet

R1[F].

and

R2

be two contrasting

such

a single

instance

[F].

minimally

in

435-80.©

Cambridge

University

Press.

This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more

2003)b.information,

and

the

Dispersion

Theory

of

Contrast

(Flemming

1995,

2006,

that

xR1,

y

R1

Œ

R1

and

x

R2,

yR2Œ

R2.

R

1

a

n

d

R

2

c

a

n

n

o

t

d

i‰

e

r

see

Le

t http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/

xR1, yR1, xR2, yR2 be segmen. ts that can be specoifinelyd for the

LarDist

(1v0)-[F]

Padgettin

2003,

Sanders

Chiosáin

a

single

instance

of Nı́

[F].

If two cont

eac

h].have

w&1oaPadgett

segments

laryrastin

ngea2003,

lgfroots

eatur

e [F

LettR

nd R2 b2009).

eth

twatoma

conytbe

rasspec

tingified

roots, such

the The

first cpaper

onstrain

t is

intended as

to pe

nalize just

{ktypology

’ap’, k’api}ofbularyngeal

t allows {k’a

pi, kapi}, which does not

is

organised

follows.

The

coat xthey

and xR2,di‰er

and R1=R2, ex

cept that

R1, ydo

R1Œ

yR2ŒinR2

then

notR1

minimally

[F].

for [F],th

Loccurrence

(2v1)-[F]

penalises

a an

minimal

given

out

w2,

w3 inoutlines

thelaryngeal

contrast

sa

tAR

isfD

y IST

theLet

“if”restrictions

uRyse

≠

1R1

.isI, fylaid

xR2

R1

dsexgin

R2

rcontrast

ets[and

F],

then

Rba1ean

deR

nnot

di‰er only

xcla

R1y,two

,yR2

xtoR2

b

e which

meacontains

n

tha

can

sp

ci2fica

edof

for

the

feature

between

roots

each

of

another

segment

specimarkedness

approach

the

phenomenon.

w4

reports

the

results

a perinl feature

a single[F].

instance

of

[F].R2 be two contrasting roots,

la

ry

ngea

Let

R

1

and

such

ISTindividual’s

(1v0)-[F] is ability

more to

general

; it penalises

a

fied

for that

feature.testing

LARDan

ception

experiment

distinguish

laryngeal

arDist

(1v0)-[F]

xstr

R1L

,ain

yinR1

Œgiven

R1

and

xR2,

ytR2afeature

Œ

1of

nlaryngeal

dd R2

odte d{ik‰er

th

e seconthat

dcontrast

conb.

t ais

m

ore

stringen

ndR2.

it inR

te

nade

to two

ecxacnln

uroots

’api,only

kofapi} and {k’api, kap’i} as

minimal

laryngeal

between

each

contrasts

between

pairs

of

roots.

The

analysis

co-occurrence

If two

contrasting

roots each have two segments that may be specified

in a with

single

instance

of [F].

well

as {k’ap’i,

k’api}

and allows

just {kapi,

k’ap’i}in w5, building on the rerestrictions

systemic

markedness

is given

for [F], then they do not minimally di‰er in [F].

sults of the perception experiment. w6 compares the systemic markedness

approach with previous analyses of laryngeal restrictions, and w7 concludes.

6

e

minimal contrast in a given laryngeal feature between two roots each of

y

kapi]}, {[kap’i, kapi]} and {[k’api, kap’i]}. Like candidate (e), candidates

(f)–(j) satisfy highest-ranked LARDIST(2v1)-[ejective], but incur excessive

violations of faithfulness, and are thus eliminated by high-ranking

IDENT[ejective]. The tableau in (27) shows the evaluation of contrasting

pairs with homorganic stops. With H-LARDIST(1v0)-[ejective] lowranked,

dissimilation

holds regardless

of place of articulation.

(27) Shuswap:

dissimilation

in ejection (homorganic)

{/k’ak’i, k’aki, kak’i, kaki/} LarDist Ident LarDist H-LarDist

(2v1)-[ej] [ej] (1v0)-[ej] (1v0)-[ej]

**!

*****

*****

a. {k’ak’i,

k’aki, kak’i, kaki}

Gillian

Gallagher

*

***

*** canb.

{k’aki,

k’aki,

kaki}

™{[k’ati, kati]}, {[kat’i, kati]} and {[k’ati, kat’i]}, eliminating

kat’i]},

**! shows dissimilation, loses

c. {k’ak’i,

didates (a)–(d),

(f)kaki}

and (g). Candidate (c), which

due

to the contrasts {[k’ati, kati]}, {[kat’i, kati]} and {[k’ati, kat’i]}.

Gallagher, Gillian. “Perceptual Distinctness and Long-Distance Laryngeal Restrictions.” Phonology 27, no. 3 (2010),

DIST(1v0),

but candidate

Candidates

(e) and

(h)–(j)

allThis

satisfy

435-80.© Cambridge

University

Press.

content L

is AR

excluded

from our Creative

Commons license. For more

(e)information,

preserves

two forms instead of one, and is thus preferred by

see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

of Shuswap

in (26) and

is a specific instantiation of the

[ejective].

The formulation

of L(27)

ARDIST(1v0) to penalise positional

IDENTanalysis

(2v1)-[F]7I

ranking

schema

for

dissimilation

:

LARDIST

• typo:

b is {k’aki,

k’i, kaki}of assimilation,

contrasts

is crucial

to thekaanalysis

as candidates

(e)DENT

and[F]

(f)

ARDIST(1v0)-[F], H-LARDIST(1v0)-[F]. Given this ranking, neutral7L

AR

D

IST

(2v1).

do equally

well

on

faithfulness

and

low-ranking

L

• if athe

pair

of rootscontrast

each havevsa.n1)

ejeisctiv

e then th

ey cannot cothe

ntrastvsm

by virtue of the

isation

weakest

required.

Neutralising

. inimally

1

The of

tableau

in (33) shows (2

that assimilation

also

results when 2homcontrastpr

to

one

laryngeal

eseforms

nce

or with

absenc

econsidered.

of

ejection:feature

excludeallows

s C’VC’for

V vst.hree

C’VCcontrasting

V

organic

pairs

of stops

are

forms,

as

opposed

to

the

two-way

contrast

that

results

from

neutralisation

(33) Chaha: assimilation in ejection (homorganic)

to a form with two laryngeal features. When homorganic and heterorganic

{/k’ak’i, k’aki, kak’i, kaki/} LarDist Ident LarDist H-LarDist

(1v0)-[ej] [ej] (2v1)-[ej] (1v0)-[ej]

**

*****

a. {k’ak’i, k’aki, kak’i, kaki} *!****

*!**

*

***

b. {k’aki, kak’i, kaki}

**

™ c. {k’ak’i, kaki}

Gallagher, Gillian. “Perceptual Distinctness and Long-Distance Laryngeal Restrictions.” Phonology 27, no. 3 (2010),

435-80.© Cambridge University Press. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more

LARDinformation,

IST(1v0)-[ejective] forces neutralisation of contrasts in ejection in

see http://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

roots with other voiceless stops, but not other voiced stops, as can be seen

• tableau

if a pair in

of roots

iffer inallejection

then they

differvoiceless

in ejection

in the

(34). dHere,

combinations

of must

ejective,

andmaximally, i.e. at each C

voiced stops are evaluated in parallel. The contrasts {k’adi, kadi} and

(1v0), constraints

because [g m

d]ustbear

are not

outtobysystemic

LARDIST

A{gat’i,

majorgati}

question

theseruled

appeals

contrast

facethe

is what is the candidate set

feature [voice] and thus cannot contrast for [ejective].

over which the constraints are operating? This remains an outstanding research question.

(34) Chaha: no assimilation between ejectives and voiced stops

----{/k’at’i, k’ati, kat’i, k’adi, gat’i, LarDist Ident LarDist H-LarDist

(2v1)-[ej]

(1v0)-[ej]

kadi,

gadi, kati/}

(1v0)-[ej]

Choi, John.gati,

1992.

Phonetic

underspecification

and[ej]

target

interpolation:

an acoustic study of

*!****

**

a.

{k’at’i,

k’ati,

kat’i,

k’adi,

gat’i,

Marshallese vowel allophony. UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 82

gati, kadi, gadi, kati}

*20, 287-333.

*!**

{k’at’i,

kat’i,Feature

k’adi, gat’i,

gati, Phonology

Clements,b.G.N.

2003.

Economy.

kadi, gadi, kati}

Flemming,

Edward (1995, 2002). Auditory Representations

in Phonology. Garland Press, New York

**

™ c. {k’at’i, k’adi, gat’i, gati, kadi,

gadi,

kati}

Flemming, Edward (2004). Contrast and perceptual distinctiveness. Bruce Hayes, Robert

***!* Bases of Markedness. Cambridge

d. {k’at’i,

gati,

kadi, Steriade

gadi, kati}(eds.) The Phonetic

Kirchner,

and

Donca

In Chaha, the ranking of LARDIST(1v0)-[ejective] favours assimilation,

University Press, Cambridge. 232-276.

as in candidate (c), over dissimilation, as in candidate (b). Candidate (d),

which eliminates all forms with only a single ejective, incurs excessive

Fl

emming, of

Edw

ard (2006).The

The winning

role of dicandidate

stinctivene(c)

ss cneutralises

onstraints ithe

n ph

violations

faithfulness.

1onol

vs. 0ogy. MIT ms.

contrast in roots with two voiceless stops, {[k’ati, kati]}, {[kat’i, kati]} and

{[k’ati,

roots

Marymaintaining

Beckman, &the

Jan1 Evsd.w0acontrast

timeone

is necessary but not always

Ko

ng, Eukat’i]},

n Jong,while

rds. 2012in. Vo

ice with

onsetonly

voiceless stop {[k’adi, kadi]} and {[gat’i, gati]}. The violations of LARDIST

sufficient to describe

acquisition of voiced stops: The cases of Greek and Japanese. Journal

constraints in (34) are given in (35).

of Phonetics 40, 725-44.

Gallagher, Gillian. 2010. Perceptual distinctness and long-distance laryngeal restrictions. Phonology

27, 435-80.

Padgett, Jaye. 2003. Contrast and post-velar fronting in Russian. Naturtal Language and Linguistic

7

Theory 21.1, 39-87.

Appendix on [voice]

Various phonologists (Iverson, Ringen, Jessen, Vaux, and others) argue that the Germanic languages

differ in the feature that contrasts /p,t,k/ vs. /b,d,g/: English, German [spread gl], Dutch [voice].

This position is critiqued by Kingston and Lahiri (K&L).

•

proponents of [spread gl] point to the fact that in many contexts there is no phonetically

observed voicing and therefore this is prima facie evidence that [spread gl] is distinctive

•

K&L term this an “essentialist” view of a feature: this is a core set of phonetic correlates that

should appear in every realization [±F] of the feature (cf. structuralists invariance condition

on phonemes). They deny this, at least for [voice], claiming that a voicing contrast can be

implemented by a variety of phonetic gestures whose distribution and magnitude vary

according to context and no one gesture has privileged status. What unites them is a

perceptual integration.

•

voicing in sonorants, stops, and fricatives is phonetically diverse but yet they pattern as a

natural class for the past tense and plural allomorphs in English (assumes z and d are not the

defaults).

•

passive voicing is really actively and purposely produced

•

perceptual integration to give an “intermediate perceptual property” IPP. Performed by the

auditory system and can occur even when sound in not heard as speech: low frequency of F0

(and F1) with vocal fold vibration and duration of consonant with preceding vowel duration.

•

permits a more abstract view of a distinctive feature; so apparently VOT will integrate with

high F0 to define the voiceless value signaling the open glottis gesture in the adjacent vowel.

8

MIT OpenCourseWare

http://ocw.mit.edu

24.961 Introduction to Phonology

Fall 2014

For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms.