Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference

advertisement

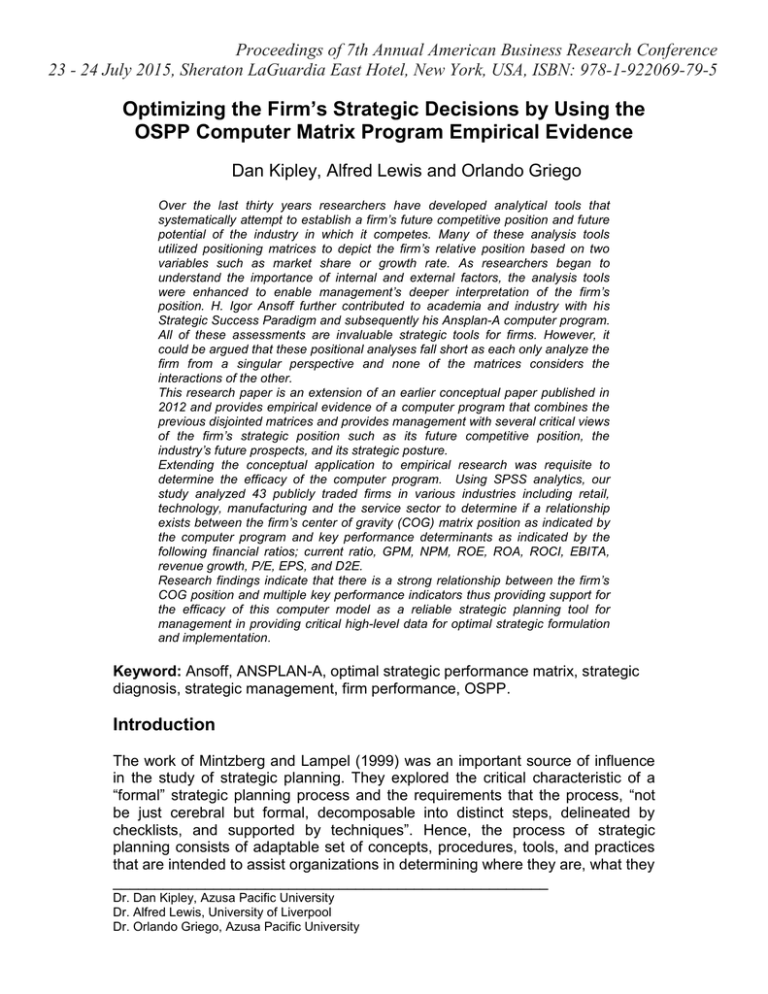

Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Optimizing the Firm’s Strategic Decisions by Using the OSPP Computer Matrix Program Empirical Evidence Dan Kipley, Alfred Lewis and Orlando Griego Over the last thirty years researchers have developed analytical tools that systematically attempt to establish a firm’s future competitive position and future potential of the industry in which it competes. Many of these analysis tools utilized positioning matrices to depict the firm’s relative position based on two variables such as market share or growth rate. As researchers began to understand the importance of internal and external factors, the analysis tools were enhanced to enable management’s deeper interpretation of the firm’s position. H. Igor Ansoff further contributed to academia and industry with his Strategic Success Paradigm and subsequently his Ansplan-A computer program. All of these assessments are invaluable strategic tools for firms. However, it could be argued that these positional analyses fall short as each only analyze the firm from a singular perspective and none of the matrices considers the interactions of the other. This research paper is an extension of an earlier conceptual paper published in 2012 and provides empirical evidence of a computer program that combines the previous disjointed matrices and provides management with several critical views of the firm’s strategic position such as its future competitive position, the industry’s future prospects, and its strategic posture. Extending the conceptual application to empirical research was requisite to determine the efficacy of the computer program. Using SPSS analytics, our study analyzed 43 publicly traded firms in various industries including retail, technology, manufacturing and the service sector to determine if a relationship exists between the firm’s center of gravity (COG) matrix position as indicated by the computer program and key performance determinants as indicated by the following financial ratios; current ratio, GPM, NPM, ROE, ROA, ROCI, EBITA, revenue growth, P/E, EPS, and D2E. Research findings indicate that there is a strong relationship between the firm’s COG position and multiple key performance indicators thus providing support for the efficacy of this computer model as a reliable strategic planning tool for management in providing critical high-level data for optimal strategic formulation and implementation. Keyword: Ansoff, ANSPLAN-A, optimal strategic performance matrix, strategic diagnosis, strategic management, firm performance, OSPP. Introduction The work of Mintzberg and Lampel (1999) was an important source of influence in the study of strategic planning. They explored the critical characteristic of a “formal” strategic planning process and the requirements that the process, “not be just cerebral but formal, decomposable into distinct steps, delineated by checklists, and supported by techniques”. Hence, the process of strategic planning consists of adaptable set of concepts, procedures, tools, and practices that are intended to assist organizations in determining where they are, what they ____________________________________________________ Dr. Dan Kipley, Azusa Pacific University Dr. Alfred Lewis, University of Liverpool Dr. Orlando Griego, Azusa Pacific University Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 should be doing, how to do it, and why (Bryson, 2004). Traditionally, the historic paradigmic approach used by management was to follow a three-step method; 1). Setting goals and objectives 2). Determining alternative solutions and strategic formulation 3). Implementing the feasible alternative (Ackerman, 1970; Allison, 1970; Bower, 1970; Carter, 1971; Cyert & March, 1963; Mintzberg, Raisinghani, & Theoret, 1976; Witte, 1972). Several normative approaches to the design of strategic planning systems have been offered by Ackoff (1970); Grant and King (1982); Andrews (1971); Ansoff (1971, 1984); Porter (1980,1985); Bryson (2004); Cohen, Eimicke, and Heikkila (2008); Mulgan (2009); and Niven (2008); however, these models have had limited applicability and utility in the decision-making process when involving multiple critical variations in decision situations. Nonetheless, the three-step method in the strategic decision-making process is fundamental in determining the future course and optimal strategy of a firm as well as having an impact on the functions of the firm, its direction, administration, and structure. In spite of this, the three-step method falls short when examining the interrelationship between all of the strategic decision-making variables, specifically, the firm’s strategic posture and strategic budget, with the future industry prospects and the firm’s future competitive position. Extant research conducted by Bourgeois, 1984; Eisenhardt & Zbaracki, 1992; Glaister, 2008; Hrebiniak, Joyce, & Snow, 1988 support the necessity of integrating the elements of normative strategic planning with an analysis of the external environment and the strategic choice perspectives in models of the strategic decision process. The purpose of this article is, thus, to contribute to the understanding of strategic positioning and performance in organizations. More specifically, it addresses two issues: Is there a relationship to be found among the firm’s financial ratios in the context of high performance and the positional display on the (Optimal Strategic Performance Positioning) OSPP matrix? Is there continuity in the performanceposition relationship between certain classes of businesses? In this study, strategic analyses were conducted on manufacturing, service, merchandise, and trade. Comparisons were made with respect to certain attributes that are specified in the first section of this paper. The second section consists of methodology discussions and choices, while the third section presents the relatedness patterns and performance effects. The findings and limitations are finally discussed and this leads to conclusions, implications, and recommendations for further studies. History The OSPP computer model was developed as an extension of Dr. H. I. Ansoff‘s seminal work on a robust, interactive, strategic management computer program designed to integrate the analytical power of the computer with the experiential heuristics of senior management. Ansoff‘s ANSPLAN-A was based on the empirically proven Strategic Success Paradigm (Ansoff et al., 1993), which was confirmed reliable as a Tier 3, strategic analysis system. At introduction, Ansoff‘s ANSPLAN-A was at the forefront of Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 the industry in strategic analytics. The program was explicitly designed to be robust as well as intricately detailed in data assessment yet simple to use requiring that managers only need to respond to a detailed list of possibilities for strategy and capabilities as well as providing an estimate of the future competitive importance and probability of the respective potentials. The data collection for the ANSPLAN-A was achieved using four modules; Module 1 focused on the firm‘s current practice and the prospects available in the strategic business area (SBA). During this analysis, the historic and present performance as well as its products and strategies are held in abeyance with the overarching focus on the identification of those threats, opportunities, growth, and profitability prospects that are available to the SBA. Module 2 estimates how well the SBA will perform if it follows its current strategy using a range of uncertainties from pessimistic to optimistic. Module 3 combines the previous modules and arrives at a decision point between an immediate commitment to a future strategy or a gradual commitment based on keeping options open for as long as possible. At this point, the software will guide the manager through a series of consequences for each choice. If immediate commitment is chosen, current strategies, capabilities to support the strategy, and the requisite strategic investment are calculated to support the choice. Module 4 is the final step in which the program identifies those programs and subprojects that must be launched to ensure implementation of the project. Although Ansoff‘s intent was to design a management tool with ease of use, it was all but that as navigation was difficult, data screens were unintuitive, and the program was plagued with constant ‗freezing‘ during data input and computations. Current Industry Analysis Tools The SWOT analysis is a simple structured framework that is used to evaluate the firm‘s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities as well as the threats. Although it is important to have an awareness of these four factors, the SWOT alone does not provide management with the firm‘s future competitive position, the industry prospects, nor its strategic posture. An extension of the data derived from the SWOT, the Internal Factors Evaluation/External Factors Evaluation (IFE/EFE) are simplistic strategic tools used to evaluate the firm‘s internal strengths and weaknesses (IFE) and the firm‘s external available opportunities and threats (EFE). The Competitive Profile Matrix (CPM) is a valuable strategic management tool that compares one firm to other firms (competitors) in the industry. The CPM uses critical success factors and assigns various weights relative to the importance in the firm‘s industry. The CPM is very valuable as it shows the relationship of one firm to its competitors, however, that is all the information the tool provides. The BCG GrowthShare Matrix utilizes a 2x2 grid to facilitate management in determining which areas of the firm (products or business units) deserve more resources and investment based on the Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 relative market share and market growth rate. The GE-McKinsey Matrix is similar to the BCG Matrix in that it positions business units on a 9-cell grid of the industry based on the business unit strength and industry attractiveness. Although both matrices show a position of current performance for the firm it remains a singular view of the firm strategic position. The Strategic Position and Action Evaluation (SPACE) Matrix provides the company with a recommended type of strategy to pursue based on analyzing the internal strategic dimensions (financial, competitive) and the external dimensions (industry strength, environmental stability) although this matrix is more advanced than the previous matrices, it still falls short of a total analysis of the firm‘s future competitive position and future industry prospects. It is thus evident that the current strategic analysis tools, although important and useful, fall short of providing management with a complete positional/performance analysis of the firm. The OSPP Model The Optimal Strategic Performance Positioning (OSPP) model is based on the principles of Ansoff‘s ANSPLAN-A model which has its foundation embedded in the Strategic Success Paradigm, specifically; industry environmental turbulence level (ETL) assessment, firm‘s strategic aggressiveness (SA), and general management capability responsiveness (CR) must be in alignment in order for the firm to achieve optimal strategic potential. Des Thwaites and Keith Glaister (1993) state, ―to succeed in an industry, an organization must select a mode of strategic behavior which matches the levels of environmental turbulence, and develop a resource capability which complements the chosen mode‖. The OSPP adds robustness to the analysis by integrating industry data on two future variables: 1. Future competitive position and 2. Future industry prospects Comprised of 11 data collection screens, a data summary output screen, and an assessment screen. The OSPP matrix is based on four measured variables. 1. 2. 3. 4. Strategic Posture Strategic Investment Future Competitive Position and Future Industry Prospects The results of the four variables are plotted on the matrix illustrating the firms‘ position relative to the ―optimal strategic position.‖ Strategic Posture Strategic Posture is defined as the combination of the Environmental Turbulence Level, Strategic Aggressiveness, and general management Capability Responsiveness. In this Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 first phase, managers perform a detailed analysis of the industry‘s future ETL from a list of 36 turbulence-level ―‗descriptors‖ encompassing both Industry Assessment (Figure 1) Figure 1. ETL Assessment – Industry and Macro Environment Assessment (Figure 2) and classify their input on a range from 1 (placid and stable) to 5 (surpriseful and discontinuous). The ETL results are then calculated and transferred to the summary output screen. Figure 2. ETL Assessment – Macro Environment Assessment Analyst will thereafter assess the firms‘ ‗SA‘ level by measuring both their Innovation Aggressiveness and Marketing Aggressiveness. Managers complete a series of 14 innovation-aggressiveness ―descriptors‖ (Figure 3) and 11 marketing-aggressiveness ―descriptor‖ (Figure 4) questions and the results are calculated and transferred to the summary output screen. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Figure 3. Present Strategic Aggressiveness – Innovation Figure 4. Strategic Aggressiveness - Marketing At this point, the program has calculated the first ―gap‖ analysis between the ETL and SA. The Strategic Aggressiveness Gap is entered into the summary output screen. The final component used to determine the firm‘s Strategic Posture variable is the assessment of Firm‘s Capability Responsiveness (CR). Capability Responsiveness assesses the firm‘s propensity and its ability to engage in strategic behavior that will optimize attainment of the firm‘s near and long-term objectives in two complementary ways: (a) by observing the characteristics of the firm‘s responsiveness behavior—for example, whether the firm anticipates or reacts to discontinuities in the environment and (b) by observing the capability profiles of the firm that produce different types of responsiveness. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 The data gathered to assess CR is generated by completing five survey screens measuring; 1). General Managers Capabilities (Figure 5), the function responsible for the overall performance of the firm. Figure 5. Capabilities Responsiveness – General Managers 2). Firm Culture (Figure 6), whether hostile, passive, or predisposed to change. The propensity toward risk—whether as a group, management avoids, tolerates, or seeks risk (familiar or novel). The time perspective – past, present, or future based. The action perspective – internal or externally focused. The goals behavior – seeking stability, growth, or innovation. The change trigger – crisis, unsatisfactory performance, or continual change. Figure 6. Capabilities Responsiveness - Culture Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 3). Firm Structure (Figure 7) - whether formalized, centralized, flexible, and management focus. Figure 7. Capabilities Responsiveness – Structure 4). Firm Systems (Figure 8) – The organization system for decision-making strategy ranges from extrapolation to deductive analysis to impact analysis/stochastic. Each represents a family of systems within which, each type of the specific systems share a distinctive perception of the future environment of the firm. The figure shows that although different in intent, the systems are built of building blocks that perform identical functions in each system. The management system, even if responsive to the firm‘s needs, will be ineffective if other components of the firm‘s capability do not support it. Figure 8. Capabilities Responsiveness – Systems 5). Firm Technology (Figure 9)– Assesses the current analytical model being used, the firm‘s level of technological development, research & development, product and process Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 investments relative to the industry leader as well as the type of surveillance system currently in use. Figure 9 is used to determine the technological aggressiveness of the firm‘s strategy and identification of the gaps. Each factor lists several descriptors that together determine what is called the Present Systems Responsiveness Level. The importance of the respective factors to the firm‘s future business strategy can be assessed as follows: Determine the gaps between the future environment and the firm‘s historical strategic position. Provide an estimate of the firm‘s future technological competitive position if the firm continues using its historical strategy. Identify the changes in the technological strategy factors that should be made. If the technology assessment shows that the firm‘s technologies are turbulent and that they play an important role in the future success of the firm and that R&D investment will be significant, it becomes desirable to synthesize the strategic variables into a statement inclusive of the firm‘s technology strategy. Figure 9. Capabilities Responsiveness – Management Technology 6). Capacity of Management (Figure 10) simply assesses whether the firm has a sufficient number of general managers and support staff to create and sustain strategic and profit making activities. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Figure 10. Capabilities Responsiveness – Management Capacity The results of each of the seven surveys are calculated and entered into the summary output (Figure 13); in addition, the ―component gaps‖ for each assessment are entered into the summary page. At this point, a second Capabilities Responsiveness Gap is determined and entered into the summary output. Strategic Budget (ISTRATEGIC) The Strategic Budget is defined as the investment committed by management to the strategic development of the firm. Economic theory and practice both suggest that the firm‘s profitability will be proportional to the size of its investment. The Strategic Budget is assessed using two screens measuring the firm‘s total commitment of resources for facilities and equipment (operations), developing the firm‘s products and processes (R&D), market position (marketing) as well as the supporting capabilities in management, production, sales, (operations) relative to the market leader. Figures 11 & 12 illustrate the surveys used for both the Capacity Investment (CI; 9 descriptors) and Strategic Investment (SI;12 descriptors) of the firm relative to the market leader, which is the ISTRATEGIC Opt. The Strategic Investment Ratio is determined and expressed in the formula; ISTRATEGIC Opt = 5 (coef CI) (coef SI), in which the firm‘s competitive position will be in proportion to the ratio of the firm‘s investment into an SBA to the level of investment that will produce optimal profitability. The Strategic Budget completes the second variable required to determine the firm‘s matrix position. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Figure 11. Strategic Budget – Capacity Investment Figure 12. Strategic Budget – Strategic Investment Future Competitive Position The firm‘s future competitive position is assessed relative to the industry by using both hard data (obtained from measurements and statistical data such as financials, market share, ROI, ROA, ROE, etc.) and soft data (views and opinions from qualified individuals, such as industry analysts or experts in the industry who contribute their expertise, judgments, and predictions about the inputs, estimation process, and outcomes). Managers complete a 26-point survey (Figure 13) of ―competitive descriptors‖ to determine the firm‘s future competitive position in its industry. For each attribute managers identify and enter the characteristic that best describes the future conditions of the industry using a numerical scale and assign numbers to each element. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Figure 13. Future Competitive Position Future Prospects of the Industry The final variable required to complete the OSPP assesses the future prospects of the industry (i.e., is the industry still relevant to serve the consumers ―need‖?). The data used to determine industry future prospects are gathered from industry publications, statistics, governmental reports, as well as informed subjective estimates from managers, customers, and industry news. Managers complete an 18-point survey (Figure 14) analyzing the future prospects of the industry the computer program allows the user to assign numbers to each factor, averages the data, and enters the results in the summary page. Figure 14. Future Prospects of the Industry Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 OSPP Company Assessment The logic of the OSPP is illustrated in Figure 15. As mentioned, the first step of the analysis was to determine the future ETL of the industry. The initial assessment of the environment is a critical element for the entire diagnosis as its value specifies the type of strategic behavior necessary for success. Research conducted by Davis, Morris, and Allen (1991) and Calantone, Garcia, and Dröge (2003) confirm the proper assessment of the industry‘s ETL as a foundational cornerstone to formulating a successful strategic plan. The ETL assessment is illustrated in Figure 15 as 3.21. The SA of the firm in display reveals two components— Innovation Aggressiveness and Marketing Aggressiveness. Both are combined and the average SA of the firm is determined. In addition, each component gap is displayed for manager‘s assessment allowing an increased granularity for strategic planning. The SA is displayed in Figure 15 as 3.01 with a gap of 0.20. The assessment of the General Management Capabilities Responsiveness (CR), is displayed (3.11) as well as the total CR gap 0.10 and each of the general management component gaps. The component gaps are also displayed by the application of an enunciator panel of green, yellow, and red lights. Green indicates an acceptable gap, yellow is cautionary, and red indicates a gap >0.50. Manager and analysts can quickly assess the firm‘s overall alignment via the enunciator panel. The four matrix variables are now displayed indicating the results of the Strategic Posture, Strategic Budget, the Firm‘s Future Competitive Position, and the Future Industry Prospects. Figure 15 illustrates the results as 4.05, 3.27, 3.16, and 3.14. Figure 15. Company Assessment A rigorous investigation on both the classification mechanism and key performance indicators (KPI‘s) was conducted on 43 organizations to determine the relationship Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 strength between the center-of-gravity (COG) position as illustrated on the OSPP computer model and financial KPI‘s. The OSPP Matrix Screen The results from the matrix variables are now plotted on the display matrix as illustrated in Figure 15. The nexus of the vertical and horizontal variables are displayed indicating the firm‘s ―Center of Gravity‖ (COG). The COG is the firm‘s performance position relative to optimal performance positioning. Optimal performance positioning on the matrix is achieved by positioning the firm in the highest proximity to the top right corner of the matrix. (Note: Managers must consider that industries and industry conditions vary, and as such, what may be the optimal position for one industry, may be different for another industry; hence a lower position on Interpreting the Matrix As can be seen from Figure 15, the Firm‘s Strategic Posture, Strategic Investment, Firm‘s Future Competitive Position, and Future Industry Prospects are positioned as a result of the OSPP Summary Page, with the firm‘s COG indicating a relatively strong position on the matrix in zone 1. The horizontal and vertical lines intersect in one of the sixteen cells in the OSPP matrix. The firm‘s performance position is then indicated by the intersection of the x-axis and the y-axis (COG) along with a recommended strategy. The four zones are illustrated in Figure 16. Zone 1 indicates the firm performance position is Optimal. The Strategic Posture and Strategic Budget are both very high and are in alignment. As well, the Firms Future Competitive Position and Future Industry Prospects are very high. Strategic recommendations are for aggressive, intensive, grow and build strategies. Recommended strategies should focus on market penetration, market development, and product development. From the operational perspective, backward integration, forward integration, and horizontal integration should also be considered. Zone 2 indicates that the firms Strategic Posture ranges from the Moderate to Optimal range. As well, the Firms Future Competitive Position range is from Poor to Moderate. What is critical in this region is the position of the Strategic Budget and Future Industry Prospects. If the firm has a low Strategic Budget (<3.0) and high Future Industry Prospects (3>) management has a misalignment with its Strategic Posture and Strategic Budget and recommendations are to increase the Strategic Budget. Such increases will improve the Firms Future Competitive Position and its Optimal Performance. If however, the Strategic Budget is high (>3) and the Future Industry Prospects are low (<3) the firm should consider aggressive cost management strategies and/or divestment or harvesting strategies. Zone 3 indicates that the firm is in a Moderate to Poor position. Although the Future Industry Prospects range from Moderate to High (>3), the Strategic Budget is Low (<3). What is of critical importance in this region is the relationship of the Firms Strategic Posture and the Firms Future Competitive Position. If the Firms Strategic Posture is low Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 (<3), the firm is gravely misaligned with its Strategic Aggressiveness and its Capabilities to the prevailing level of Environmental Turbulence, this misalignment coupled with a low Strategic Budget indicate a Poor performance position. Major strategic posture corrections are required as well as a complete assessment and improvement of the firms supporting capabilities. If, however, the Firms Strategic Posture is high (>3) the recommendation is to increase the Strategic Budget to support the Strategic Posture. Such increases will both improve the Strategic Budget Position and improve the Firms Future Competitive Position and its Optimal Performance. Zone 4 indicates that the firm is in a Poor performance position. Most typically the firms Strategic Posture is poor (<3) and the Strategic Budget is poor (<3) as well as the Future Industry Prospects (<3). Strategic recommendations include following an exit end-game strategy of harvesting or divestment. Figure 16. OSPP Assessment The OSPP is both descriptive and prescriptive as managers can now easily assess which area of the firm in which to concentrate its resources to improve its performance position. In this case, the matrix reveals that management can increase its Firm Strategic Posture and Firm‘s Future Competitive Position. Research Findings Corporate Performance has commonly been measured in relatedness studies by accounting or market-based objective measures. (Farjoun, 1998; St. John & Harrison, 1999). As optimal firm performance is the context of this study and is also a corporate construct, the measures chosen for this study was the firm‘s financial ratios and matrix position. Market-based objectives as well as other similar external measures are generally more distant from the firm‘s internal activities, such as strategic aggressiveness and capabilities responsiveness, than are financial-based measures. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Results Data were based on 61 organizations assigned to a zone position based on the OSPP Zone or on company category. Zone 1 companies accounted for 57.4 percent, Zone 2 for 6.6%, Zone 3 for 16.4 percent, and Zone 4 for 19.7 percent. In addition, there were 18.0 percent manufacturing companies, 45.9 percent merchandising or trade companies, and 36.1 percent service companies (see Tables 1 and 2). Table 1. Frequency and Percent of Zone Position Zone Position Frequency Percent Cumulative Percent 1.0 35 57.4 57.4 2.0 4 6.6 63.9 3.0 10 16.4 80.3 4.0 12 19.7 100.0 Total 41 100.0 Table 2. Frequency and Business Category Business Category Frequency Percent Manufacturing 11 18.0 Merchandising or Trade 28 45.9 Service 22 36.1 Total 41 100.0 Cumulative Percent 18.0 63.9 100.0 An Analysis of Variance was done to determine differences between the 4 zone positions and the 15 key indicators. To assess a violation of variance a test of homogeneity of variance was accomplished. Strategic Posture, Current Ratio, NPM, EBITDA, ROE, ROCI, and D2E violated assumptions (see Table 3). When variances are very unequal, and/or the group sample sizes are small and unequal, as was the case in this study, a Welch F test was used as an alternative to avoid Type I errors. Post hoc tests that met the assumptions were analyzed using a Tukey HSD while those that failed to meet assumptions used Games-Howell which takes into account unequal variance. The ANOVA or Welch F Test determined there were eight significant findings. They are as follows: There was a significant difference in Zone position in Strategic Posture using the Welch F Test [F (3, 16.52) = 5.52, p = .008]. Further post hoc analysis using Games-Howell determined Zone 1 (M = 3.47, SD = 0.63) had significantly higher Strategic Posture than Zone 3 (M = 2.60, SD = 0.82). Additionally, Zone 2 (M = 3.64, SD = 0.23) was significantly higher than Zone 3 (M = 2.60, SD = 0.82). There was a significant difference between Zones in Strategic Budget [F (3, 57) = 31.39, p < .001]. The Tukey HSD post hoc analysis determined Zone 1 (M = 3.34, SD = 0.72) scored significantly higher on Strategic Budget than both Zone 3 (M = 1.85, SD = 0.74) and Zone 4 (M = 1.51, SD = 0.58). In addition, Zone 2 (M = 3.92, SD = 0.51) scored significantly higher than Zone 3 (M = 1.85, SD = 0.74) and Zone 4 (M = 1.51, SD = 0.58). There was a significant difference in Zones in Future Competitive Position [F (3, 57) = 31.39, p <.001]. The post hoc test using Tukey HSD determined Zone 1 (M Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 = 3.67, SD = 0.39) had significantly greater Future Competitive Position than Zone 2 (M = 2.53, SD = 0.38) and Zone 4 (M = 2.50, SD = 0.47). Moreover, Zone 3 (M = 3.29, SD = 0.46) scored significantly higher than both Zone 2 (M = 2.53, SD = 0.38) and Zone 4 (M = 2.50, SD = 0.47). The Future Industry Prospects showed significant differences in Zones [F (3, 57) = 5.46, p = .002]. Further post hoc analysis using Tukey HSD determined Zone 1 (M = 3.67, SD = 0.39) had significantly greater scores than Zone 2 (M = 2.75, SD = 0.12). There was a significant difference in the four Zones related to NPM using the Welch F Test [F (3, 11.71) = 3.55, p = .049]. A Games-Howell post hoc analysis determined Zone 1 (M = 14.93, SD = 24.37) scored significantly higher than Zone 4 (M = -2.85, SD = 15.13). There was a significant difference in the Zone quadrants in ROE using the Welch F Test [F (3, 18.10) = 17.12, p < .001]. A post hoc analysis using Games-Howell determined Zone 1 (M = 23.34, SD = 13.02) showed significantly higher ROE than Zone 2 (M = 2.16, SD = 3.96). There was a significant difference in Zones within ROA [F (3, 57) = 9.10, p < .001]. A post hoc analysis using Tukey HSD determined Zone 1 (M = 11.17, SD = 7.81) showed significantly higher ROA than Zone 2 (M = -9.03, SD = 18.43) and Zone 4 (M = -5.82, SD = 18.67). There was a significant difference in Zones in ROCI [F (3, 10.02) = 7.91, p = .005]. Using a Games-Howell post hoc test showed Zone 1 (M = -17.54, SD = 11.17) was significantly greater than Zone 3 (M = -0.54, SD = 16.30) and Zone 4 (M = -16.76, SD = 31.02). Both GPM and EBITDA showed significant results. However, robust tests of equality of means cannot be performed because at least one group had zero variance. Table 3. Test of Homogeneity of Variances Using Zone Position Key Indicator Strategic Posture Strategic Budget Future Competitive Position Future Industry Prospects Current Ratio GPM NPM EBITDA Revenue Growth ROE ROA ROCI D2E PE EPS Levene Statistic .019* .734 .938 .210 .019* .096 .004* .028* .718 .000* .123 .010* .000* .378 .279 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 *p<.01, Indicates violation of assumptions and Welch F Test used Table 4. ANOVA for Zone Position on Key Indicators Mean (SD) Zone 1 3.47 (0.63) Mean (SD) Zone 2 3.64 (0.23) Mean (SD) Zone 3 2.60 (0.82) Mean (SD) Zone 4 2.79 (1.09) Strategic Budget 3.35 (0.72) 3.92 (0.51) 1.85 (0.74) 1.51 (0.58) 34.71* Future Competitive Position 3.67 (0.39) 2.53 (0.38) 3.29 (0.46) 2.50 (0.47) 28.64 * Future Industry Prospects 3.67 (0.39) 2.53 (0.38) 3.20 (0.17) 3.11 (0.35) 5.46* Current Ratio 2.06 (1.38) 0.00 (0.00) 2.46 (3.00) 1.43 (0.40) 0.85 GPM 43.50 (18.80) 0.00 (0.00) 27.36 (22.34) 38.68 (15.50) † NPM1 14.93 (24.37) -38.00 (53.63) 3.40 (9.84) -2.85 (15.13) 3.55* EBITDA 17.22 (12.50) 0.00 (0.00) 5.62 (12.64) -2.34 (18.17) † Revenue Growth 11.72 (13.42) 8.78 (10.54) 5.05 (6.99) 2.32 (8.20) 2.39 ROE1 23.35 (13.02) 2.18 (3.96) 3.97 (20.90) -34.11 (101.21) 17.12* ROA 11.17 (7.81) -9.03 (18.43) 0.66 (9.55) -5.82 (18.67) 9.10* ROCI1 17.54 (11.34) -21.50 (36.72) -0.54 (16.30) -16.76 (31.03) 7.91* D2E 6.74 (23.06) 1.28 (1.72) 0.88 (0.55) 45.62 (87.74) 1.66 PE 127.04 (534.97) -52.90 (141.15) 8.90 (21.07) 2.99 (8.03) 0.52 EPS 11.04 (36.10) -0.56 (0.83) 0.83 (3.12) -1.33 (2.76) 0.84 Key Indicator Strategic Posture1 F or Welches F Test 5.52* *p < .01, 1 = Welch F Test analysis, † = Cannot determine significance since one group had zero variance Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Another Analysis of Variance was done to determine differences between the 3 business categories and the 15 key indicators. Once again a test of homogeneity of variance was accomplished. There were no violation of assumptions (see Table 4). As before, post hoc tests that met the assumptions were analyzed using a Tukey HSD. There was only one significant finding. There was a significant difference in Business Category in GPM [F (2, 57) = 3.22, p = .047]. The further post hoc analysis using Tukey HSD determined Service (M = 44.91, SD = 20.38) scored significantly higher than Merchandising or Trade (M = 33.21, SD = 20.05). There were no other significant findings. See Table 5. Table 4. Test of Homogeneity of Variances Using Company Type Key Indicator Levene Statistic Strategic Posture .199 Strategic Budget .617 Future Competitive Position 1.000 Future Industry Prospects .913 Current Ratio .179 GPM .920 NPM .666 EBITDA .069 Revenue Growth .650 ROE .405 ROA .192 ROCI .415 D2E .096 PE .065 EPS .328 *p<.01, Indicates violation of assumptions and Welch F Test used Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Table 5. ANOVA Company Type on Key Indicators Mean (SD) Manufacturing 2.95 (0.75) Mean (SD) Merch - Trade 3.45 (.70) Mean (SD) Service 3.03 (.97) Strategic Budget 2.79 (0.87) 2.99 (1.08) 2.50 (1.19) 1.21 Future Comp Position 3.41 (0.75) 3.30 (0.61) 3.25 (0.65) 0.22 Future Industry Prospects 3.19 (0.29) 3.19 (0.33) 3.27 (0.34) 0.40 Current Ratio 1.88 (0.97) 1.94 (1.19) 2.20 (2.30) 0.20 GPM 38.75 (21.87) 30.21 (20.05) 44.92 (20.38) 3.22* NPM 11.35 (11.41) 4.44 (37.28) 5.50 (14.69) 0.26 EBITDA 17.32 (17.59) 10.75 (10.80) 6.34 (18.80) 1.89 Revenue Growth 6.37 (13.59) 9.32 (8.53) 8.75 (14.95) 0.24 ROE 16.86 (26.09) 9.70 (34.44) -0.04 (72.72) 0.45 ROA 7.62 (9.89) 4.78 (10.98) 3.36 (18.38) 0.34 ROCI 11.58 (17.35) 5.07 (20.00) 2.37 (31.82) 0.52 D2E 0.60 (0.60) 18.58 (57.13) 12.29 (36.67) 0.64 PE 14.48 (20.59) 138.97 (602.98) 14.07 (13.28) 0.70 EPS 6.05 (12.79) 9.47 (39.74) 2.04 (8.45) 0.43 Key Indicator Strategic Posture *p < .01 F 2.34 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Discussion A summation of the findings brings to light key differences. Within the business category, the one significant finding was Service scoring significantly higher than Merchandising / Trade in GPM. Most of the significant differences were related to the OSPP Zone quadrants. In summation, the following were significant and noteworthy: With respect to Strategic Posture, both Zones 1 and 2 showed significantly higher scores than Zone 3. Comparing Strategic Budget, both Zone 1 was significantly greater than Zone 3 and 4. Additionally, Zone 3 was significantly higher than Zone 4. There was a significant difference in OSPP Zone positions in Future Competitive Position. Zone 1 indicated higher Future Competitive Position than Matrix 2 and Matrix 4. Moreover, Zone 3 was significantly higher than Zone 2 and Zone 4. Future Industry Prospects showed significance with Zone 1 scoring higher than Zone 2. There was a significant difference in Zones related to NPM. Zone 1 recorded significantly higher than Zone 4. There was a significant difference in Zone position in ROE. A post hoc analysis using Games-Howell determined Zone 1 showed higher ROE than Zone 2. There was a significant difference in Zones with respect to ROA. Zone 1 was significantly higher than both Zone 2 and Zone 4. There was a significant difference in Zones in ROCI. Zone 1 was significantly greater than both Zone 3 and Zone 4. Both GPM and EBITDA showed significant results, but there were violations in group variance. No other significant results were found outside of these. Contributions of this study The purpose of this study was to provide empirical validation of the OSPP computer application as an effective tools for determining a firm‘s strategic position and to validate its ability. The OSPP computer application provides positional plotting versus the firm‘s financial performance plus determines if a relationship of position/performance did indeed exist. The results of the study indicate that the overall approach and methodological framework was proven valid as it clearly shows a significant difference in OSPP Zone position and financial performance. As a result, it can be stated that the OSPP computer program does provide managers and analysts with an effective analytical tool in which to identify the firm‘s strategic position, thus enabling management with valuable information to plan proactive measures to best guide the firm. Moreover, the study shows that the OSPP is more effective at determining strategic position than industry grouping alone (e.g., manufacturing, merchandising/trade, or service). Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Conclusion The paper presents result based on extending a previous study which examined the contribution by Ansoff (1986). The extension was to strengthen the instrument utilized to determine a firm‘s strategic position. The Optimal Strategic Performance Position Matrix© (OSPP, 2012) extended Ansoff‘s ANSPLAN-A model by adding and integrating two critical variables; future competitive position and future industry prospects to the existing four variables measuring; environmental turbulence, strategic aggressiveness, capabilities responsiveness and strategic budget. SPSS 22.0 software was utilized to analyze 61 publicly traded firms in a variety of industries such as manufacturing, merchandising/trade, or service in order to ascertain if there is a relationship between a firm‘s center of gravity (COG) matrix position as indicated by the OSPP and key performance determinants as indicated by the following financial ratios; current ratio, GPM, NPM, ROE, ROA, ROCI, EBITA, revenue growth, P/E, EPS, and D2E. The results indicate that a strong relationship exists between a firm‘s COG position and multiple key performance indicators. As such, the OSPP matrix computer model is a reliable strategic planning tool for management in providing high-level data which can be utilized in the strategic planning and management process to achieve optimal strategic formulation and implementation. Recommendations for Business Managers and Analysts The previously mentioned conclusions illuminate the effectiveness of the OSPP program and as such provides managers with an analysis tool that is relatively easy to use, yet affords those decision makers with a comprehensive assessment tool for identifying the firm‘s strategic position. Unlike traditional analysis tools, the OSPP computer application is a dynamic analysis program that can benefit management by identifying and analyzing the multiple critical variables for organizational success and their interrelationship with each other to determine an all-inclusive evaluation of the firm. Therefore it is recommended that both managers and analysts include in their strategic decision making process a tool that can provide a holistic view of the firm‘s strategic position. References Ackerman, R. W. (1970). Influence of integration and diversity on the investment process. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15, 341-352. Ackoff, R. L. (1970). A concept of corporate planning. New York, NY: Wiley. Allison, G. T. (1970). Essence of decision. Boston, MA: Little Brown. Andrews, K. R. (1971). The concept of corporate strategy. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Ansoff, H. I. (1965). Corporate strategy. New York, NY: McGraw- Hill. Ansoff, H. I. (1984). Implanting strategic management. New York, NY: Prentice Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Hall. Ansoff, H. I. (1986). Competitive strategy analysis on the personal computer. Journal of Business Strategy, 6(3), 28-36. Ansoff, H. I., Brandenburg, R. G., & Radosevich, R. (1971). Acquisition Behavior of U.S. manufacturing firms, 1946-1965, Vanderbilt Press, Nashville. Ansoff, H. I., Sullivan, P. A., Antoniou, P., Chabane, H., Djohar, S., Jaja, R., Wang, P. (1993). Empirical proof of a paradigmic theory of strategic success behaviors on environment serving organizations’. In D. E. Hussey (Ed.), International review of strategic management (pp. 173-203). New York, NY: John Wiley. Bourgeois, L. J. (1984). Strategic management and determinism. Academy of Management Review, 9, 586-596. Bower, J. L. (1970). Managing the resource allocation process. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Bryson, J. M. (2004). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Carter, E. E. (1971). The behavioral theory of the firm and top-level corporate decision. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16, 413-429. Calantone, R., Garcia, R., & Dröge, C. (2003). The effects of environmental turbulence on new product development strategy planning. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20, 90-103. Cohen, S., Eimicke, W., & Heikkila, T. (2008). The effective public manager: Achieving success in a changing environment (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Cyert, R. M., & March, J. C. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Davis, D., Morris, M., & Allen, J. (1991). Perceived environmental turbulence and its effects on selected entrepreneurship, marketing, and organizational characteristics in industrial firms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 19, 43-51. Farjoun, M. (1998). The independent and joint effects of the skill and physical bases of relatedness in diversification. Strategic Management Journal 19 (7): 611-630. Eisenhardt, K. M., & Zbaracki, M. J. (1992). Strategic decision making. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 17-37. Glaister, K. W. (2008). A causal analysis of formal strategic planning and firm performance. Management Decision, 43, 365-391. Glaister, K. W. & Thwaites, D. (1993). Managerial Perception and Organizational Strategy. V18. (4). The Braybrooke press. Grant, J. H., & King, W. R. (1982). The logic of strategic planning. Boston, MA: Little Brown. Hrebiniak, L. G., Joyce, W. F., & Snow, C. C. (1988). Strategy, structure, and performance. In C. C. Snow (Ed.), Strategy, organizational design, and human resource 3, pp. 3-54). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Kipley, D., Lewis, A.O., & Jeng, J.L. (2012). Extending Ansoff’s strategic diagnosis model: Defining the optimal performance positioning matrix. Sage Open, http://sgo.sagepub.com.content/early/2012/01/10/2158244011435135. Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Mintzberg, H. D., & Lampel, J. (1999). Reflecting on the strategy process. Sloan Management Review, 40, 3, 21-30. Mintzberg, H. D., Raisinghani, D., & Theoret, A. (1976). The structure of unstructured decision processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 246-276. Mulgan, G. (2009). The art of public strategy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Niven, P. R. (2008). Balance scorecard step-by-step for government and nonprofit agencies (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York, NY: Free Press. Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage. Free Press: New York. St. John, C., & Harrison, J. (1999). Manufacturing-based relatedness, synergy, and coordination. Strategic Management Journal 20 (2): 129-145. Witte, E. (1972). Field research on complex decision making processes—The phase theorem. International Studies of Management & Organization, 2, 156182.