South Canterbury Coastal Streams (SCCS) Limit Setting

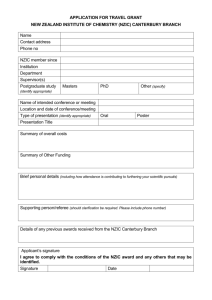

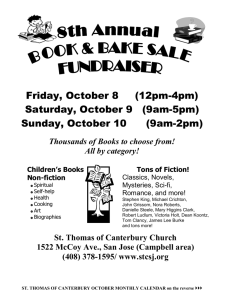

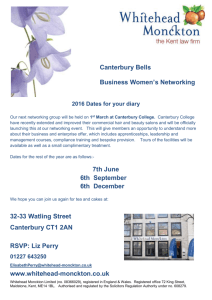

advertisement