Expanding Access and Opportunity How Small and Mid-Sized Independent Colleges

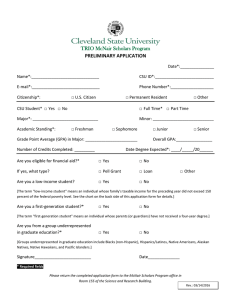

advertisement