The Religious Environmental Movement: Its Current State and Future Madeline Priest

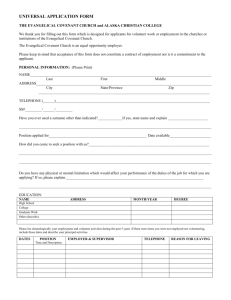

advertisement