Colours in abundance and bundles - the sale of Chinese... at the auctions of the Scandinavian East India Companies

advertisement

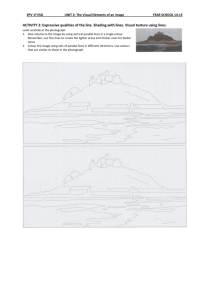

Colours in abundance and bundles - the sale of Chinese silk textiles at the auctions of the Scandinavian East India Companies References to add: David Michell in Journal of Textile History 2010 Pippa the Hangzhoy Silk Museum http://ebwg.sunbo.net/index.php?xname=OVRD401 Slide 1. The paper I about to give here is based on research I am currently doing as part of a project on East India Trade together with Meike Fellinger, Felicia Gottmann, Chris Nierstrazs. The name of the project is “Europe’s Asian Centuries: Trading Eurasia 1600-1830” and it is headed by Maxine Berg. As it happens I also work on another post doc project in Sweden. It is on the legacy of Carolous Linnaeus and the late 18th century natural history links between London and Uppsala. I mention it here because, the work with this paper I have given me reasons to look at aspect to do with botany and entomology. The different East India Companies of early modern Europe are our main focus of attention in the Warwick project. I work on the Scandinavian East India Companies, the Danish and the Swedish Companies: o “Asiatiska kompaniet” o Svenska Ost Indiska Kompaniet. The two companies were on the one hand quite different. The Danish Company, established already in 1616, traded with China as well as India, where the company had a chain of trading stations. The Swedish company on the other hand was a much slimmer operation, established in 1731 it almost exclusively traded with China. However, although different in terms of organisation and history, the Scandinavian companies had a lot in common too. As companies based in small neutral countries they were well placed to compete with the bigger companies during periods of European conflicts. Their ships were also frequently used to bring home the fortunes of particularly the English East India Companies’ employees in Asia, as part of the so called remittance trade. Moreover, and particularly important here, the goods the Scandinavian East India Companies brought to Gothenburg and Copenhagen were to a large extent re-exported. This was the case for between 70% and 90% of the goods. The main reason for this was that the Scandinavian populations was too poor to consume the luxuries from the east. Moreover, the high duties on tea in Britain made smuggling a lucrative business. In fact the trade with tea from China provided the main drive for the Scandinavian East India ventures. However, tea was not the only goods brought over from the East. Indian textiles and Chinese porcelain and silk were other goods that were shipped over and sold at auctions in Copenhagen and Gothenburg. Again goods that to a large extent was re-exported. It is in order to understand first of all the role of Copenhagen and Gothenburg as peripheral emporiums for East India goods: including the transnational European trade with Asian goods That I have developed an interest in colours and particularly the colours of silk textiles brought over from China. Although in terms of bulk or Cargo, the quantity of Chinese Silk was not very significant, it was how ever a very valuable commodity. I will get back to some of my future plans, and how a study of colours might illuminate the consumption of Chinese Silk in Europe towards the end of the paper: Hoping that feedback from you might help develop some of my plans. For the first and longest section of this paper I am going to focus on the names of the colours of the silk and the relationship between colours and price. Slide 2 However I will start with the source l have been working with first My first example is from a catalogue listing the goods for sale in Gothenburgh in August 1748. This stuff had been brought from China by the two ships Calmar and Kronprinsen which set out in 1746, and it lists tea, porcelain and silk material for sale. What makes this sales catalogue particularly interesting is the fact that the prices the stuff was sold for is listed, together with the name of the purchaser. The section covering the silk starts with a little introduction saying that: Prior to the auction, the textile had been on display in the house of Joh. Freid Bruun, who lived by the Great Harbour (this is before the Swedish East India Company invest in their own magazines). The Catalogue also statues that since any purchaser had had the chance to examine the pieces beforehand they had no right to refuse a lot which they bought: o but for the exception if it was shorter than stated, and that had to be with more than a Swedish aln, which is about 60 centimetre. Slide 3 All in all 9857 Pieces were for sale in 395 lots. There were 5 general qualities but only 3 in any substantial quantities: 4996 Damask pieces: Damask is a fabric with a none raised pattern in the same colour as the background fabric. The Damasks for sale in Gothenburg are described as either “Meuble” or “Poises” (i.e. a flower bouquet). Only 400 out of nearly 5000 Damask pieces were described with the help of a pattern number. About 10 pattern numbers 3250 Taffeta pieces: Is a smooth plain woven fabric, can either be pieced dyed or yarn dyed. The Taffeta for sale in Gothenburg is distinguished as 4, 6, or 8 threads 1040 Paduasoy: originally a French terms a strong corded or grosgrain silk textile Others qualities: There are also some pieces named “Gorgoroner” and Satin for sale But the Damask, Taffeta and Paduasoy made up the main bulk of the textiles for sale, about 90%. Specifications: Next to name the lengths and the width is specified. There were standard three lengths with some small variations: 13.8-14.1m; 16.2-16.65m; 22.8-23.7, Width when specified was 1.25 m. Colour: These were not the only way in which the textile were described or defined, added to the above parameters was the one of colour Slide 4 In fact, colour seems to matter a great deal, maybe not surprisingly since silk is a textile fibre that absorbs dyes easily. All in all there are 26 colours mentioned in the sale catalogue. With the exception of a handful of fabrics that are described as stripy the colour of every piece is specified. With this information I have created this circle diagram. I have tried to match the colour of the segment with the actual colour referred to. So the biggest segment, the blue one, represent the number of pieces which are described as “Sky blue” in the catalogue. Needless to say I have sometimes guessed what colour or shade is referred to with certain names. On the hand out is a list of the names and my translation of them. The order in which the colours are listed reflects how common they were, so sky blue was the most common colour. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Slide 6: Before we look closer at the list of names of colour – there are a few things to say about the concept of colour in the 18th century. The 18th century was a very dynamic period when it comes to developing theories or systems for how to categorise colours, including nomenclatures and descriptions of them. Like Sara Lowengard has discussed The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe this was an area where science and trade merged. She makes the point that in order to understand the role and development of colours in the 18th century we need to keep the perspective broad. Lowengard identifies three different strands: One is rooted in physics and Newton’s descriptions of colours They were based on observations of a colour spectrums produced by illuminating a prism. These are the same colours you can detect in a rainbow. Newton identified 7 colours sometimes called principle colours; o red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. The second strand of discussion of colours was one to which trades men and manufacturer largely contributed. Here there are different ways to think about colours stemming from manufacturing processes. Basic colours were the colours different groups of tradesmen worked with. Dyers were traditionally separated into different groups of pending on if they worked with red, yellow, blue, black etc. Basic colours in ceramics and enamelling were black, white, yellow, green, blue and purple colours, again different trades men tended to specialize in one colour. Dyers and manufacturers also worked with the notion of primary colours, i.e. blue, red and yellow. This colours were of course important, because of the wide range of secondary colours you can produce by mixing them. Similar, black and white, not colours in the physical sense of the word (indicating the absence of colour or the presence of all colour) were important. o Because the ability of shading any paint by adding black or white to the mix. Next to basic colours, primary and secondary colours was the notion of a simple colour which was a colour produced only by one ingredient. The influence of manufacturing on the nomenclature of colours is also possible to trace in names where the production of these colours originated from. Hence we talk about Saxon green, or Prussian Blue (first manufactured 1707). See also Cologne earth, or Cassel earth, (both brown). Now, this is not to say that nomenclature of colours were necessarily stable among tradesmen and manufacturer. While the production of colour contributed to the variation in naming and understanding of colour and colour production. Fashion could disturb the order. Old colours were re-launched with new names, enabling sellers of e.g. textiles to recycle goods and dies. The third strand in the discussion of colours in the 18th century emanates from natural history. In fact 18th natural history contributed to the discussion of colours in two ways. The first was overlapping with the discussion taking place among those focused on manufacturing. Natural history was here a tool with which help the natural world could be explored so as to find the sources for new dies. In fact, the objective, to find new sources for colours in the natural world is a very dominating theme in the natural history discussion of the time. Secondly, the 18th century saw the development of a more exact language for describing nature, a development to which the Swedish naturalists Carolus Linnaeus was central. Linnaeus was careful of using colours to identify for example plants, since he recognised that the colour of a flower changed depending on where it grew. Nonetheless naturalists needed to take into account colours and in response to a growing need to develop a more precise language of colours like: the Danish Johan Christian Schäffer or the German Abraham Gottlob Werner They created taxonomic colour systems with which help they tried to encourage more exact descriptions of nature. Slide 7 While often rejecting names for colours that evolved within the context of fashion, e.g. Prussian blue> Their attempts to creates systems and names for how to mix different colours contributed to the discussion of colours in the 18th century. And with this in mind I would like to go back to the list of names in the Swedish Auction catalogue. First of all, the names used here are part of European, and maybe particularly French dominated nomenclature for referring to colour. Poneceau (French for Poppy) Couleur de Rose Couleur de Chair Paille Blomerant from French Bleu mourant Turqvin blue probably from Turquin marble Mazarin blue, dark blue, named “in honour of “ Cardinal Mazarin, Richelieu’s predecessor This pay witness to the influence of French fashion, French silk was high fashion in 18th century Sweden. In order to explore this further I searched Svenska akademiens ordbok, SAOB, the equivalent of Oxford English Dictionary' outlining the etymology of words used in the Swedish language from 1521. Searching the terms listed on the handout the proximity natural history, chemistry and fashion, as discourses, contributing to the nomenclature of colours becomes very clear. In many cases, the colour names on my list have their first recorded usage within a natural history context, o sky blue for example is first used in 1538, to describe the colour of the lily Iris germanica. o Jonquil, similarly, is cross referenced with the plant Narcissus jonquilla. The other references to Jonquil is to the flora Swedish Lichens by Westring, (1805) on here it says it is a colour of a dye that could be extracted from Bloodspot lichen ("blodplättlav) A further observation is that when clothes are mentioned, they are in many cases referring to silk clothes specifically, o there are for example many references to sky blue silk dresses, pearl grey stockings etc. This is not surprising since of course silk textile where the most colourful of the textiles available to early modern European consumers before Indian cotton fabrics became available on a broad scale. But it also raise the question to which extent it was within a area of silk manufacturing and consumption that the early modern colour nomenclature for bright colour developed. Robert Finlay, in "Weaving the Rainbow: Visions of color in World HIstory" lists names for colours used by common people in England at the time, often washed out brown, blues and grays. Here we find names such as "horse flech", "gooseturd", "rat's colour", "peas porridge" and "puke". In France we find names such as "flea's belly", "Paris mud" and "goose-droppings". Maybe needless to say, I have not come across any of these names when I studied sales catalogues or order lists from the trade with China About the dating of the colour references: several of the names on my list do only seem to have come into use in the late 17th and 18th century: Poneceau (first used in 1666) and Blomerant (first used in 1665) the first recorded use of these terms are from the 16660s Paille first used in 1718 There are no recorded uses of the terms Coul. de Rose until 1778 and Coul. De Chair until 1801. In other words my sales catalogue predates the etymology described in SAOB. Although this is not a solid proof that these terms were not in use before it does suggest that they were relatively new. Another indication of the relative novelty of the terminology in the catalogue is that there are no references at all in SAOB to the names “Mazarin blue” and “Turquin blue”. There could be several reasons for this. As we know from previous research from the late 17th century there was a annual fashion cycle in silk dress-fabric taking place in France and England: Already in 1680s the East India Company took this into account: o “Note this is for Constant and General Rule that in all flowred Silkes, you change ye fashion and flower as much as you can every year, for English Ladies and they say ye French and other Europeans will give twice as much for a new thing not seen in Europe before though worse, than they will give for a better silk of ye same fashion worn ye former yearse.” (Records of Ford George’s: Despatches from England, 1680-1682, ed. H. Dodwell, Madras 1914, p. 51, London to Hughly, 20th of May 1681, from John Styles, “Product innovation in Early Modern London, p. 134, foot note 27, see here also references to work by Peter Thornton. See also Nathalie Rothstein who also argues, the production of silk textiles in 18th century Europe were determined by trends, changing so frequently that silk manufacturers rarely produced large amount of silk in one design, if it was not pre-ordered.) Maybe the fact that colour terms such as Mazarine blue and Turquin blue are not picked up is because they were short lasting trends in fashion. Moreover, as I said initially, much of what was brought to Gothenburg was re-exported. The influence of a transnational Europea and particularly French terminology in the colour nomenclature is therefore not surprising, given the fact that so much of the stuff brought to Gothenburg was re-exported. Silk manufacturing in France was of course together with that in England leading the development in Europe. A brief comparison the names for colours used in the Swedish catalogue with colour references used referring to Chinese silk in the other East India Companies we can see that there is an established international terminology. In the ordering lists of EIC we can find the term Sky blue for example. Here we also have the term Straw coloured, which I assume is the same thing as Paille, and Mazarine blue. Bleumerant is one of the most common colour in a Danish sales catalogue from 1756. There is however a global dimension to the terminology visible in the list of names of colours to. Karmine or Crimson in English, was generally the result of a dye called Kermes, which was made of the insect Kermococcus vermilis planchon. It had been used for red colours in the whole of Eurasia since the prehistoric period, including China. The dye was called Kermes and many European and Asian languages have a name for red which is derived from the word kermes, including here Karmine and Crimson In other words, the nomenclature for colours in the Swedish sales catalogue capture not only the influence of French Fashion on 18th century Europe But also a history of trade dating back many centuries, and stretching over vast geographical areas. A note here on the colour of red and yellow, as Meike pointed out to me, these were actually colours which were reserved for the emperor, and officially no trade in them were allowed. Slide 8 However, as Paul van Dyke has discussed, this did not stop the Canton merchants from trading in these colours, in fact extensive bribing made this trade very common. To which extent it was shared use of dyes, and/or the use of samples, that helped bridge the understanding of what the European wanted when they made their order to the Hong merchants in Canton is a question I will return to later on. What the auction catalogue however suggest is that the there was a need to distinguish between not only different colours but also different shades of colours. There are for example: 6 different colours of blue (Sky blue, dark blue, mazarine blue, light blue, Blue Turqvin, and Blomerant) 5 different colours of red including Pink, (Crimson, Scarlet, Poncea, Coloure de Rose, Colulure the Chair) 3 different colours of grey (Ash coloured, Pearl Coloured, Lead Coloured) 3 different shades of yellow, (Jonquil, Lemon Yellow and Paille) In this context I think it worth comparing this relatively exact terminology for distinguishing and defining the colours of Chinese Silk fabric with the references to colours in discussions about Indian textiles in the EIC. Here I am drawing on work that Chris, Felicia and Meike and I did last year on the ordering lists of the EIC, i.e. the correspondence from London to different trading stations in India about what to buy. What characterise this discussion is a much more vague language. For example and referring to an order of Chintz Ahmadavad, there were requests for “lively brisk colours (09/10) but nothing more specific. Sometimes some colours are ruled out, e.g. In 09/10 there were request for Chintz, but “no blacks or stripes” In 1740, in correspondence with the Coromandel coast there were requests for bright red colour but not “dead brick colour” In 1740, corresponding with Bengal there were request for Chintz Patna, “all white ground, part of them with springs and part running work of three colours but none with yellow in them” In 1740, about an order for Chintz from Calcutta, it states “to be of good colours without any green or brick colours” When colours are referred to they are often only referred to as simply white, green, blue or red. Moreover, colour references seem to be used mainly when specifying the grounds of the textiles, on which patterns were printed or painted. And these patterns are often described in very vague tones, often referred to as either “large” or “small”, or being “running” or “set work”, containing “flowers”, “sprigs”, “stripes”, “Nosegays”, “Checks”, or simply “Indian Fancy”. Of course the vagueness of this orders were to a certain degree compensated with the use of pattern and colour samples, and with references to previous years’ imports. However, compared to the sales catalogues from Gothenburg, as well as ordering lists from the other companies, the trade in Chinese Silk comes across as much more standardised than the trade in Indian textiles. To anyone familiar with the complexity of names and qualities of Indian textiles for sale in the 18th century this might come across as a fairly banal conclusion. Moreover, Euroasia shared a much longer and richer history of silk production and consumption. Cotton was not as prominent in Europe before the East India Companies started trading with India. However, the conclusion that the trade in Chinese silk was more standardised, might become more interesting if we pause to think about how colours contributed to the standardisation. And in this respect the list of colour names I gave you on the hand out is slightly misleading, since it does not reflect the proportions of pieces sold in different colours. Slide 9 Compare for example the colours of the Damask for sale, the most common of the quality of Chinese silk textile for sale in 1747. All in all this Damast was sold in 21 out of 26 colours. Slide 10 However, as this diagram might illustrate better, the main bulk of the Damsk for sale was coloured in one of only 16 colours. Slide 11 The same goes for the Taffeta, the second most common fabric for sale. It was sold in 17 of the 26 colours. Slide 12 But the company held significant holdings in only 15 out of the 26 colours listed. Slide 13 The Paduasoy however was offered in a greater variety of colours. There were Paduasoy for sale in 23 of the 26 colours. Slide 14 And as this diagram illustrate, there was a greater spread. Slide 15 However, as this last diagram illustrate quite well, most of the textiles from China were largely in only one out of 16 colours. Slide 16 We can compare that with the number of colours referred to in the Danish East India Company’s auction 9 years later, in 1756 here there were only significant holdings in 13 different colours. Slide 17 So far on the variation of colours that Chinese silk came in. What is just as important is that the textiles were sold in lots, containing pieces of many different colours, and they sold for different prices. Take for example the 4310 pieces of Damask first listed in the Swedish sales catalogue. They were sold in lots of between 29 and 37 pieces, each peice being 16.5 meters long and (I assume 1.25 meter wide). Slide 18 The highest price was paid for lots 934-964. All in all 30 bundles of textiles which each contained 31 pieces, made in 16 different colours. The lowest price was paid for the last lot, which contained 37 pieces, but which only contained 6 different colours Slide 19 This way of selling textiles, in lots with several different colours represented, was not I suspect, unique to Sweden, but did I think represented a common way of selling Asian textiles at auctions and to wholesalers. Take e.g. the instructions or orders from London to their different trading posts of the English East India Company in South Asia. These orders do not only specifying: how much of one specific type of textile they wanted, the size of the pieces, which patterns sometimes also which colour that they should have. They also contain detailed instructions on how to assemble bales of textiles: In the order to Bombay in 1740, to purchase 5000 pieces of Chintz Caddy, it also state that the order should be made up of: o One third brown grounds, one sixth white grounds, the remainder in Red grounds In the order to Bombay of Chintz Nassermany, in 1740, it states: o More variety of colours, and one half of the piece in each bale must be of four colours In other words: Although London don’t specify colours beyond some very rough divisions into red, blue, brown etc. But they do give instructions about the proportions of textiles of with different colours that should be packed into in each bale. It is the compilation of textiles pieces that seems to be important. These are just a few examples of many of instructions on how to assemble bales, or chests with textiles. It is easy to imagine that these bales or chest were sold as they had been packed in India. Each bale containing a variety of pieces, with different patterns and colours. If this was how textiles were sold whole sale in London it does also become easier to understand how the warehouses handled all the novelty in patterns that they constantly requested. The orders and instructions to South Asia are full of demands for “more new patterns” and “more variation” By selling them in bundles or mini bundles they did not need to be more precise about exactly what colour or patterns they wanted. In other words “more was more” in terms of variation of colour and patterns, but only within the limits of what was contained in each bale. Pierre Claude Reynard… Slide 20 Back to Chinese silk then, here the standardization when it comes to color seems to have gone much further, with the distinct shade of many colours making up the bundles or bales specified quite exactly. Maybe we should understand this along the line of how Giorgio Riello analyzes the European integration of Indian cotton textiles into its consumer market of Europe, with its expectations of regularly changes to patterns and colours. There are of course differences: First of all Chinese silk of have a much longer history of being consumed by Europeans than cotton. Moreover, Europe had a long tradition of domestic silk production, with a nomenclature for dies and colours attached. However, the 18th century saw a large increase in the direct trade between Europe and China, and this shift might have generated a new type of commodification of silk. Turning into a type of consumer object which was expected to change quite rapidly, shifting in shades in such a way to enticing the colour hungry Europeans? Before I end I would like to highlight some of the questions this work has left me with. And some thoughts on how one can further illuminate: the impact of the trade with Asia on European consumption and the creation for markets for luxuries and semi luxuries in Europe, Using sales catalogues and ordering lists from the Scandinavian companies. When it comes to sources: There exists quite a large collection of sales catalogues from the Gothenburgh sales: o At least up until the end of the second charter, I believe there are sales catalogues for about 1/3 of all the year. o Although to which extent they contain information about price the goods caught and the name of the buyers I don’t know. The Danish material is less comprehensive when it comes to sales catalogues. There is one catalogue from 1756 where the price for about half of all the silk for sale is listed, as well as the buyers for these lots. There is however a very rich material generated by the Danish trading in Canton. The contact between the Danish supercargoes and the Canton merchants have been document in “Negotiation-protocols”, in which one can trace the ordering of silk material, qualities and colours. o These negotiation protocols are available from 1730s when the Danish company started direct trade with Canton up until the 1830s o I looked at the negotiation protocol covering the goods for sale in 1756, and most of the colours that are ordered there are also listed in the sales catalogue. o Although the Danish seems not to have got all the blue silk they wanted. In terms of the order made the negotiation protocols does however not illuminate how the negotiation with the Hong merchants went. Silk orders were placed as soon as possible after arrival to Canton, leaving the Chinese merchants around 100 days to deliver their goods. The contract, included in the negotiation protocols does however only list which colours the different qualities of silk was to be coloured in, ending with a generic sentence that silk “should be in dyed in the best colour the country of China could provide”. There are further notices on the silk once the orders were delivered but for the year I have studied there is not very much suggesting that the Danish and the Chinese merchants were disagreeing on the colour scheme. That this was not always a simple transaction can however be illuminated with other material, on for example private trade. Meike Fellinger and I are working on material relating the Scottish supercargo Charles Irvine who worked for the Swedish East India Company. In fact it is Meike that found this example for me. In a letter to Irvine from the whole salers Cossort and Bouver, in 1740, on what silk material to buy in Canton, we can see how the Europe whole sellers provided Irvine with pattern and colour samples to bring along. The wording of the letter suggests that the wholse salers were very keen that Irvine was careful matching of what he got in Canton with the samples. I am hoping to find more material of this kind, hopefully in material generated by those who were engaged in the whole sellers of silk, frequenting the auctions in Copenhagen and Gothenburg. All in all this material would allow for a mapping of the development of colour schemes in Chinese silk qualities available to the European whole sale market involved in the re-export of silk from Copenhagen and Gothenburg from the 1730s and onwards. It might be possible to detect both general trends over the cause of the century: Long term changes in what was imported, in terms of qualities and colours, As well as more short term changes in fashion by looking at the changing nomenclature for colours. The material could quite easily be compared to ordering lists and sales catalogues available for the Dutch, French and English companies Moreover, the negotiation protocols as well as material generated by whole sellers offers opportunities to study the more fine grained discussions of colours that took place. Both between Chinese and Danish traders in Canton But also within an European context, among people who knew what to different European consumers wanted in terms of colours. References: Sara Lowengard The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe Finlay “Weaving the Rainbow”. Lillian Li, China's silk Trade