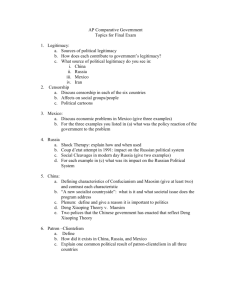

CONCEPTUALIZING INTERNATIONAL LEGITIMACY David P. Rapkin & Dan Braaten Abstract

advertisement