Sophocles Oedipus the King Antigone

advertisement

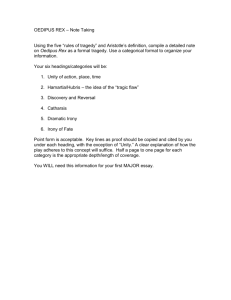

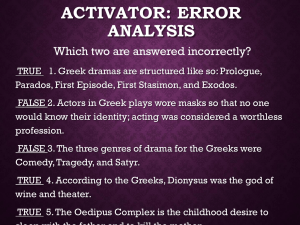

Sophocles Oedipus the King Antigone Aristotle on Tragedy: Poetics (c. 335 BC) “Tragedy is a representation of a serious, complete action which has magnitude, in embellished speech, with each of its parts used separately in the various parts of the play; represented by people acting and not by narration: accomplishing by means of pity and terror the catharsis of such emotions.” (ch. 6) Aristotle on Tragedy: Poetics (c. 335 BC) “Tragedy is a representation of a serious, complete action which has magnitude, in embellished speech, with each of its parts used separately in the various parts of the play; represented by people acting and not by narration: accomplishing by means of pity and terror the catharsis of such emotions.” (ch. 6) mimesis = imitation/representation. The goal of art, tragedy included, is to represent or imitate life. Aristotle on Tragedy: Poetics (c. 335 BC) “Tragedy is a representation of a serious, complete action which has magnitude, in embellished speech, with each of its parts used separately in the various parts of the play; represented by people acting and not by narration: accomplishing by means of pity and terror the catharsis of such emotions.” (ch. 6) mimesis = imitation/representation. The goal of art, tragedy included, is to represent or imitate life. catharsis = purgation/purification. A trickier term, and much contested. Aristotle on Tragedy: Poetics (c. 335 BC) “Tragedy is a representation of a serious, complete action which has magnitude, in embellished speech, with each of its parts used separately in the various parts of the play; represented by people acting and not by narration: accomplishing by means of pity and terror the catharsis of such emotions.” (ch. 6) mimesis = imitation/representation. The goal of art, tragedy included, is to represent or imitate life. catharsis = purgation/purification. A trickier term, and much contested. pity and terror: this pairing of emotional responses is invoked again and again by Aristotle. Aristotle on Tragedy: Poetics (c. 335 BC) 6 key parts of a tragedy (in order of importance): • • • • • • plot character thought diction music spectacle “Plot is the origin and as it were the soul of tragedy, and the characters are secondary.” (ch. 6) Aristotle on Tragedy: Poetics (c. 335 BC) The constituents of a “complex” plot: 1. A reversal in fortune (peripeteia) 2. Recognition: “a change from ignorance to knowledge” (anagnorisis) Maximum effect is achieved when these come together. Also: 3. Suffering: “a destructive or painful action, e.g. deaths in full view, agonies, woundings etc.” Aristotle and Oedipus the King Sophocles’s Oedipus the King an exemplary tragedy for Aristotle. Reversal: King becomes outcast, saviour becomes foe, curser becomes cursed, husband becomes son… Recognition: Oedipus discovers that he has killed his father and married his mother, Jocasta. Aristotle: “in the Oedipus, the man who comes to bring delight to Oedipus, and to rid him of his terror about his mother, does the opposite by revealing who Oedipus is.” **Reversal and recognition are intertwinned.** Suffering Oedipus is blinded and exiled. Aristotle and Oedipus the King The structure of the tragic plot Solution/unravelling (denouement) Complication The plague; the Oracle’s words; Oedipus’s search for the murderer of Laius; Tiresias’s cryptic revelation of the truth; Jocasta’s telling of the history of her son and the circumstances of Laius’s death. Jocasta’s suicide; Oedipus’s blinding and exile; Creon’s accession to the throne of Thebes. Reversal/recognition Discovery that Oedipus killed Laius and that Laius and Jocasta are his real parents Aristotle and Oedipus the King Tragedies, Aristotle argues, shouldn’t show: • The fall of a good man: “this is neither terrifying nor pitiable, but shocking” • The rise of a wicked man: “it is neither morally satisfying nor pitiable nor terrifying” • The fall of an out-and-out villain: “such a structure can contain moral satisfaction, but nor pity or terror”. Rather, the tragic protagonist must be someone neither supremely virtuous nor supremely wicked who suffers “because of some error, and who is one of those people with a great reputation and a good fortune, e.g. Oedipus.” (ch. 13) Hamartia Literally, “missing the mark”; usually translated as “flaw”. Neither accident nor wickedness. Free will, Fate, and the Tragic Flaw What is Oedipus’s tragic flaw? As Tiresias points out, Oedipus does not see clearly: You call me blind, you jeer at me – I say your sight is not clear enough to see Who shares your palace, nor the room in which you walk, Nor the sorrow about you… Now You have sight, but then you will go in blindness; When you know the truth of your wedding night (200) Sight and understanding are here inversely proportional. Free will, Fate, and the Tragic Flaw What is Oedipus’s tragic flaw? According to the Chorus, he has overreached in seeking greater knowledge and perfect happiness: Oedipus aimed beyond the reach of a man And fixed with his arrowing mind Perfection and rich happiness. (233) Your own mind, reaching after the secrets Of gods, condemned you to your fate. (237-8) At the end of the tragedy, the Chorus state: Remember that death alone can end all suffering; Go towards death, and ask for no greater Happiness than a life In which there has been no anger and no pain. (244) Free will, Fate, and the Tragic Flaw The Sphinx’s riddle: What is it that walks on four legs in the morning, on two at noon, and on three in the evening? Oedipus’s correct answer: A human. Ingres, Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864) Free will, Fate, and the Tragic Flaw What is Oedipus’s tragic flaw? Final irony: through his overwhelming suffering Oedipus does exceed the limits of the human. More than mortal in your acts of evil. More than mortal in your suffering, Oedipus. (237) Free will, Fate, and the Tragic Flaw If Oedipus could not have avoided his fate, how can we hold him to be flawed? E. R. Dodds (1966): No human court could acquit Oedipus of pollution; for pollution inhered in the act itself, irrespective of motive … Oedipus accepts responsibility for all his acts, including those which are objectively most horrible, though subjectively innocent. (43, 48) Terry Eagleton (2003): It is surely perverse to find a drama’s deepest value in the fact that its hero accepts responsibility for what is palpably not his fault. Perhaps there is a hint here of the public-school ethic of sportingly taking someone else’s punishment for them. Oedipus is certainly a sacrificial scapegoat, who will finally come to assume the burden of the community’s sins. (33) Free will, Fate, and the Tragic Flaw The “scapegoat mechanism” Coined by Kenneth Burke in Permanence and Change (1935), and elaborated by Rene Girard in Violence and the Sacred (1972). For Girard, the scapegoat is a violent solution to the problem of violence: • • • Communal violence projected onto a single individual, who is held responsible for strife and discord. His or her death/expulsion a means of regenerating communal bonds and restoring peace. All of this must occur unconsciously. How might this conception of the scapegoat change our understanding of catharsis? Sophocles’s “Theban Plays”: 1. Oedipus the King (c. 430 BC) 2. Oedipus at Colonus (c. 406 BC) 3. Antigone (c. 441 BC) Antigone and the limits of Aristotle’s theory Who is the tragic protagonist of Antigone? Antigone Reversal? She is already the victim of misfortune: her brothers’ deaths and “the curse of Oedipus” (255). Recognition? She fully understands what she is doing – and its implications – from the outset: “I am doing only what I must” (258). Flaw? Law-breaker? The Chorus accuse her of stubbornness: “Like father, like daughter: both headstrong, deaf to reason! | She has never learned to yield” (269). Antigone and the limits of Aristotle’s theory Who is the tragic protagonist of Antigone? Antigone Do the gods assist her? Of Polyneices’s second burial, the Sentry states: A storm of dust roared up from the earth, and the sky Went out, the plain vanished with all its trees In the stinging dark. We closed our eyes and endured it. The whirlwind lasted a long time, but it passed; And then we looked, and there was Antigone! (267) Antigone and the limits of Aristotle’s theory Who is the tragic protagonist of Antigone? Creon Flaw? Like Oedipus, he resists the will of the gods; like Oedipus he scorns Tiresias for his words of warning. As Tiresias’s states: You have kept from the gods below the child that is theirs The one in the grave before her death, the other, Dead, denied the grave. This is your crime… (287) Recognition? He does see the error of his ways but what difference does this make? Nothing is discovered. Reversal? His son and wife die but he suffers neither death or exile. He remains King. Antigone: love versus the law Creon embodies the state and its laws: “The State is the King!” (277) Antigone embodies love (as does Haimon, in a different way). At centre of the play, the Chorus sing an ode to love. Nothing sentimental here! Love, unconquerable Waster of rich men… Even the pure Immortals cannot escape you, And mortal man, in his one day’s dusk Trembles before your glory. (280) Antigone: love versus the law Agon that opens the play: Antigone Ismene LOVE/FAMILY “I will bury the brother I love.” (257) LAW/STATE “The law is strong, we must give in to the law.” (257) ACTIONS “Creon is not strong enough to stand in my way” (256). WORDS “the new law forbids it” (256) “I will keep it a secret, I promise!” (257) Antigone: love versus the law Agon that opens the play Antigone Ismene LOVE/FAMILY “I will bury the brother I love.” (257) LAW/STATE “The law is strong, we must give in to the law.” (257) ACTIONS “Creon is not strong enough to stand in my way” (256). WORDS “the new law forbids it” (256) “I will keep it a secret, I promise!” (257) Antigone: “Words are not friends” (271) Chorus, at the end of the tragedy: “Big words are always punished” (295) Bibliography Aristotle, Poetics, trans. Richard Janko (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987). Burke, Kenneth, Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose (New York: New Republic, 1936). Dodds, E. R., “On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex,” Greece and Rome, 13.1 (1966), 37-49. Eagleton, Terry, Sweet Violence: The Idea of the Tragic (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003). Hall, Edith, “The Sociology of Athenian Tragedy,” in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy, ed. P. E. Easterling (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 93-126 Girard, Rene, Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1977). Williams, Raymond, Drama in Performance, rev. edn. (London: Penguin, 1968), 7-31.