AN ESSAY ON THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS

advertisement

AN ESSAY ON T H E STATUTE O F FRAUDS

JAMES E .

COOK

Preface

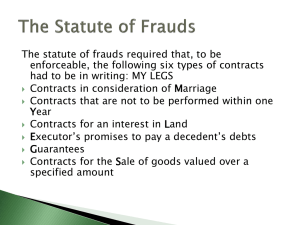

The single phrase "Statute of Frauds" can have at least two

meanings.

First, and probably foremost to a historian, the Statute

of Frauds is a shortened name used to describe the Act of 29 Car. TI,

c. 3, entitled "An Act for Prevention of Frauds and Perjuries."

Second, for the practicing American attorney, that phrase refers to,

in a general way, the rule of law which regulates either the creation

or proof of specific legal documents in his jurisdiction.

Within this paper, both of the above mentioned meanings will be

used.

Hopefully the context within which they are placed will

alert the reader as to which one is intended.

Often it will be necessary to display passages from the original

Statute of Frauds or from its contemporary decendents.

Old style

spellings will be preserved as they appear in manuscript; however,

noticable misspellings will be followed by [sic].

89

i

Introduction

The original Statute of Frauds, 29 Car. II, c,3, is perhaps

one of the most important documents in English legal history.

In

many ways, it was a dramatic break with the past; in other v;ays, it

was but another step along the traditional path of the common law.

It is the goal of this essay to highlight the importance of the

Statute of Frauds by explaining the state of the law prior to its

enactment, the social and legal reasons for its proposal, and the

effect which its passage had on the early formation of American

jurIsprudence.

The Statute of Frauds has been claimed by some alternately to

be either a rule of evidence or a rule of substance.

Those who say

it deals only with evidence explain that the Statute of Frauds describes

what is necessary in order to prove in court that a writing concerning

Blackacre is or is not a devise of Blackacre.

On the other hand, those

who insist it is a rule of substance explain that the Statute of

Frauds sets forth the necessary elements for creating a valid devise

of Blackacre.

These are, however, merely two sides of the same coin.

The Statute of Frauds must be followed when one drafts any legal

instrument; otherwise, that instrument will be inadmissible as evidence

later, should litigation be required to enforce its provisions.

Because the English Statute of Frauds, as it was originally

passed, has been repealed and supplanted, it is primarily of historical

significance now.

This is not to deny that judicial interpretations

of that first Act find life even today in modern interpretations of

that law's offspring.

But in order to understand the Statute of Frauds

90

ii

and its place in Anglo-American legal history, more attention will

be directed upon the changes wrought by the Statute than upon the

provisions of the Statute themselves.

Naturally, one cannot be done

in the complete absence of the other.

Nonetheless, the emphasis

of this essay is intended to be upon the history of the Statute of

Frauds, and not \ipon judicial interpretation.

91

iii

I.

As the title "An Act for the Prevention of Frauds and Perjuries"

indicates, the Statute of Frauds was enacted to prevent fraud, not

to punish it.

This "fraud" was not, however, a factual misrepresentation

of one man to another, but rather was very nearly the same thing as

"perjury", or a willful misrepresentation to a court.

Perjury, said

Lord Coke, was "when a lawful oath is administered, in some judicial

proceeding; to a person who swears willfully, absolutely and falsely,

on a matter material to the issue or point in question."^

Hence, the

Statute was enacted to prevent a litigant from bringing a false claim

before the court, and seeking to support it by perjured testimony.

Official sanctions against perjury existed prior to the development

of formal judicial proceedings.

Anglo-Saxon ordinances and dooms

mentioned the offense of prejury, and frequently the punishment

allotted for the lawbreaker was banishment or, in some instances, df.ath,2

In medieval England, false swearing was not only a criminal offense,

but also an offense against the laws of the Church.

The combined

effect of banishment for the temporal crime and further religious

sanctions for the spiritual crime were often enough in themselves to

prevent perjury.

It is possible, however, that the passage of the Statute of

Frauds was a tacit admission that the effectiveness of the old punitive

laws had vanished, and that men were no longer deterred from committing

perjury.

Perhaps for this reason, the drafters of the Statute of Frauds

averted their attention from punishing perjury to creating barriers to

its commission.

92

pege 2

II.

As mentioned above, there have been tv;o predominant views of

the Statute of Frauds.

Some writers have seen it as a rule of evidence;

others have seen it as a rule of substance.

Determination of whether

either view is entirely correct will be taken up later.

But as a

foundation for that time, the development of the law of evidence

should be sketched briefly now.

The law of evidence began with the transformation of the jury

from a body of witnesses to a body of fact finders.

"Nov? that the

verdict of the jury was based, ncrl on their own knowledge, but on the

evidence produced to them in court, some law about this evidence

became n e c e s s a r y . T h i s process started in the sixteenth century,

and "as a result of this development, we begin, at the end of the

seventeenth century, to see in outline some of the main principles of

cur modern law of evidence.

In 1499j however, courts considered the presentation of evidence

a luxury rather than a necessity for the jury.

Thayer describes a case

wherein a verdict was returned before the parties had presented any

evidence, and the passage from that court's opinion is as follows:

Evidence is only given to inform their [the jury's]

consciences as to the right. Suppose no evidence given

on either side, and the parties do not wish to give

any, yet the jury shall give their verdict for one

side or the other. And so the evidence is not material

to help or harm the matter.5

During the Tudor period, courts remained reluctant to admit the

evidence of parties and witnesses.^

It was still thought that the jury

should settle contested matters on their own knowledge rather than rely

9q

page

94

on the statements of interested parties or their friends,"'' However,

in earlier days it had not been uncommon, in disputes over the

genuiness of a deed, for the jury to consult with the witnesses to the

g

deed.

At that time, a witness to a deed was not required to have been

present at its signing and delivery, but was merely expected to vouch

o

for it by lending the transaction the dignity of his name.

"This

may account for its turning out so often, when witnesses were questioned,

that they knew nothing about the matter"

When the contested issues

went beyond matters of which the jury

had personal knowledge, or which were memorialized by records or

documents, or which were such publicly notorious facts as seisin,

there came to be a need for outside help for the jury."1

this involved the oral evidence of witnesses.

Often

Up to this time

(1500 - 1550) the oral evidence of witness (in the modern cense) was

seldom used.

"There was no means of compelling a witness to come

forward to testify; and, if he came forward voluntarily, he might expose

12

himself to an action for maintenance."

The old common law courts

used a writ of subpoena as early as the 1300"s, but this writ was

13

directed toward the parties to the litigation, and.not to witnesses.

As the authority of the courts became more defined, it came to be

understood thab each court had the inherent power to call for adequate

proof of the facts in controversy, including the power to summon

witnesses before it.1^

"The ordinary summons is a writ of subpoena,

which is a judicial writ,directed to the witness, commanding him to

appear at the Court, to testify what he knows in the cause therein

described, pending in such Court, under a certain penalty mentioned

94!

page U

in the writ."1''

Note: 5 Eliz. c.9 required that a witness summoned

by subpoena be paid his reasonable expenses in going

to end returning from the trial, and provided that

this witness could not be compelled to testify before

his expenses had been paid.

Rule 179t TRCP, provides for the production of witnesses

by subpoena, but states that no fine shall be imposed and

no attachment shall issue in a civil suit for that witness'

failure to attend until it is shown to the court that all

lawful fees have been paid or rendered to that witness.

With the advent of oral evidence came also the problems of

determining what sort of evidence should be admitted for the jury's

consideration.

The English court had maintained "absolute

discretion as to what averments made by counsel it would admit."^

This control of pleadings carried over to control of the admission

17

an.d rejection of evidence.

Francis Bacon determined the role of

the trial judge to be as follows:

The parts of a judge in hearing are four: to

direct the evidence; to moderate length, repetition,

or impert-inency of speech; to recapitulate, select,

and collate the material points of that whichghath

been said; and to give the rule or sentence.

The direction of the evidence was usually limited to keeping from

the jury matters which went outside the cause plead, or matters which,

in the experience of reasonable men, were \mtrustworthy and would

orobably excite or confuse the jury.

The period from 1550 to 1640

saw the refinement of the art of pleading, but also gave birth to the

exaggeration of emphasis on the form of pleading, which later drew

criticism from Dickens and others.

Also during this time, the so-call

"Hearsay Rule" grew in importance and complexity, and became the most

exception-riddled rule in legal history.

95

page 96

Thus the stage was set for the Statute of Frauds.

be called a piece of remedial legislation.

It might new

The courts presumably,

had been beseiged by bogus land transfers, contracts for sale, and

wills, and suitors of all kinds sought by way of perjured testimony,

the courts' approval of these transactions.

beset by the same problems then as now.

The jury system was

The well-educated and

affluent used their positions to stay far away from the juries,

leaving only the uneducated and unsuccessful to sit on the panel.

Also, rumors of bribery, jury tampering, and partiallity lead many

19

to forsake the common law courts in favor of the Chancery.

Something

had to be done to bring uniformity to the lav/ of evidence, and to lighten

the load on the judicial system.

As will be shown later, the success of the Statute of Frauds

at accomplishing these above mentioned goals is questionable.

Yet

it did brigr. about an awareness of the problem and an attitude that

eventually it could be solved by sweeping legislative enactment.

III.

As mentioned above, commentators on the Statute of Frauds

have been prone to categorize it as either evidentiary or substantize,

one to the exclusion of the other.

The great American jurist Dr. Simon

Greenleaf stated emphatically, "This statute introduced no new principle

into the law; it was new in England, only in the mode of proof, which

20

it required."

To test Greenleaf's announcement, we should briefly

examine the original status of the substantive law of the three main

subjects of the Statute of Frauds (contracts, conveyancing, and wills)

96!

page

97

before proceeding to the study of how these areas were affected by it.

The Anglo-Saxon Dooms and Ordinances reveal some of the earliest

regulations of commercial transactions, or sales of goods.

"If a

Kentishman buys property in London-wick, he must have as witnesses

21

two or three reliable freemen or the king's wick-reeve."

"And I

will that every man shall have his warrantor; and that no one shall

trade outside a prot, but shall have the witness of the

22portreeve or

of other trustworthy men whose word can be relied on." '

Apparently,

these laws, if broken, will not render the transaction void, but will

make the underlying contract unenforecable should dispute arise

over the legality of the deal.

"There is no evidence of any regular process of enforcing contracts,

but no doubt promises of any special importance were commonly made

by oath, with the purpose and result of putting them under the

23

sanction of the church."

In the centuries following the Dark Ages

forms of action concerning contractual obligations began to take

shape. 'Trior to the appearance of assumpsit the contractual

p / remedies

in English law were debt, detinue, account, and covenant."

"By far the commonest origin of an action of debt is a loan of

money."

25

But it was also used for the sale of goods.

Delivery of

goods, oaynent in whole or in part, or the giving of earnest money was

26

required to make a binding sale.~

Unless a written document was

available to prove up the sale, the contestants would have to resort- to

compurgation to decide the matter.

27

Detinue ley for the recovery, in specie, of goods sold to someone

23

who retained them without right.

It Is an offshoot from the action

97!

page- 7

of debt, and it appears that the tv;o forms were originally one.

29

Because the original distinction between these two forms was already

vague, and because any contract for the payment of money, which could

be proved in court, constituted a debt, the more definite form of

action for debt survived, while the action of detinue was supplanted

30

by trespass on thecase.

The action of account first appeared in 1232, but is perhaps

31

older than that.

It was "peculiar in the fact that two judements

[were] rendered, a preliminary judgment that the defendant do account

with the plaintiff . . . and a final judgment

. . . after the

accounting for the balance found due." 32 Like the action of detinue,

33

account was based upon a real contract.

But its importance to the

Ot

development of the law of contracts is minimal.

If a commercial transaction were memorialized by a scaled document,

35

the action of covenant would lie for its enforcement.

merchants or traders used a seal in their business.

But not many

In fact, it was not

until the latterof.part of the thirteenth century that such men began

to use the seal.

Nonetheless, the seal was important to such

transactions, for it was taken to be conclusive evidence of the formation

of the contract, whenever the original witnesses were- unavailable for

37

questioning.

Hence, by the time the Statute of Frauds was enacted, the English

courts had devised many forms of action concerning sales, and not all

of them required the formality of a writing or memorandum.

that the opportunity for fraud presented itself.

It is cbvic.-s

The law of contracts

needed something to standardize the forms of contracts, if for nothing

98

page

12

more than to males the work of the courts simpler.

The early law of conveyancing is even more complex than that of

contract.

"In medieval times the only estates fully recognized by the

lav/ and given protection in the King's courts v:ere the freehold estates:

38

the fee simple, the fee tail and the life estate."

Prior to the

Statute of Frauds there were only two requirements for conveying a

freehold estate: (l) \ise of limiting words, describing the estate

/

39

conveyed, and (2) livery of seisin.

When the common lav/ began to recoginse non-freehold estates, such

as the term of years, one could convey such estates by use of the

appropriate words coupled with entry by the lesses.^0

Livery of seisin and occupation of land were facts which could be

proved by questioning any adult in the county in which the land was

located.^" Memoranda need not be recorded, nor even exist, in order to

show a right to possession.

But these rules were outliving their

usefulness; for society was slowly growing more distant, and public

acts were less remembered.

In trials to establish rights in land, charters or other documents

ip

were occasionally exhibited to the jury.

They were not evidence,

though they were often so called. Rather, the charter was the very

ground of the Iaction,

and its existence was a matter of pleading and

Q

not of proof.

judgment.

If the charter was not denied- the plaintiff took

If it was controverted, then the writing's genuineness

was tested, but not its "truth or operative quality,

The Statute of Frauds, by coercion, brought changes in the law of

conveyancing.

As vail be shown below, the penalty provisions of the

12!

Act forced specified transfers of interests in land to be memorialised

and signed, lest the entire transfer be reduced to the lowest status of

estate lenown at that time.

Before the Statute of Frauds, testamentary disposition of property

was governed first by borough custom and later by the Statue of Wills.

The Statute of Wills (32 Hen. VIII, c.l) is perhaps the second most

important piece of legislation to issue from the Tudor era, excelled

only by the Statute of Uses (27 Hen. VIII, c.10).

By the Statute

of Wills, a landowner "was empowered. . . to devise all of his land

held in socage tenure and two-thirds of his lands held by knight service."

Also, the devisees were "liable for the various feudal dues as though

they took by descent."^

Some degree of formality was demanded in the execution of a m i l

in accordance with that Act, in that it required a written instrument.

But not until the Statute of Frauds were testators required to sign

LV

their will.

Seldom does one see "last will" without "testament".

"A common belief

is that this phrase [last will and testament] arose because a will

disposed of real property and a testament disposed of personal property,

;g

therefore one instrument disposing of both was a will and a testament."+

In addition, it is sometimes thought that the ecclesiastical courts

fostered the use of "testament" (coming from the Latin testamentum)^

to describe property over which they had jurisdiction, while conmon law

courts used the Saxon50will to describe property subject to their power.

Professor Mellinkoff

asserts that this pair of words was combined,

not to separate kinds of property of jurisdictions of courts, but merely

cut of a habit of coupling an Old English word (will) with its

100

page

14

synonym taken from Latin (testament), much like the combinations

51

"had and .received", "mxnd and memory", and "free and clear".

Whether or not this linguistic analysis is correct, it is

established that from the time of William I, ecclesiastical courts were

involved r.pin the probate of wills and the administration of decedents'

estates.''' The royal courts had been given jurisdiction over land

53

disputes as early as the reign of Henry I.

Thus, if a decedent's

estate involved a land dispute, a possible conflict of jurisdiction

between church and state could have arisen.

IV.

As mentioned above, the Statute of Frauds can be considered reform

legislation.

Its passage followed by only a few years the Restoration.

And the literature of the latter half of the seventeenth century

reflected a popular desire to rid the law of its outmoded and inefficient

ways.

Pamphleteers and other outspoken critics of the government of the

Interregnum had accused members of Parliament of favortisrn and the sale

of public offices, even places on the Court of Chancery.^

"Because of the mounting demands for a sweeping reform

in the existing system of justice and in the actual

content of the law as well, parliament was moved in

January, 1652, to establish aCornmission for Regulation

to review in detail the state of the law in the light

^

of these demands and to make recommendations to Parliament,"

Appointed to this Commission were, among others, Matthew Hale, Hugh

56

Peters, John Desborough, and Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper.

The Commission for Regulation met with little success. As soon

as it was formed, writers with a variety of views deluged the group with

14!

page

102

pamphlets and open letters urging reform as they saw it.

was possible.

No agreement

"In November, 1655r a judge of the High Court of

Admiralty and the Court for the Probate of Wills published a pamphlet. . .

calling for a moderate approach to the question of legal reform."

57

The writer suggested that "restauration" was the only salvation for

5S

England, though what he meant by this expression is not clear.

It might have been a plea for the return of the Stuarts.

But possibly

it was an invocation of the spirit of the common law to return and

restore the simplicity the judicial system once enjoyed.

V.

Legal historians have written extensively about the date and

59

authorship of the Statute of Frauds.

agree.

T'heir findings do not always

Nonetheless, some information is now held as established

concerning the Statute.

It is certain that the Act was the work of more than one author.

Sir Matthew Hale, Sir Leoline Jenkins, Sir Francis North, and Lord60

Nottingham have been credited with lending a hand to its drafting.

The entry of captions of early drafts of the Act in the jounal of the

House of Lords had added to the confusion, because one cannot be

sure what part others might have played in writing those drafts, and

how much, if anything, of those attempts were retained in the final

product. Nevertheless, it is safe to say that the Statute of Frauds

was the result of influences from both the bench and the bar.

The second mystery of the Act is the date of its passage.

Through-

out the body of the Statute is repeated the effective date thereof,

102!

page 103

namely, June 24, 1 6 7 7 .

But its enactment date has been disputed.

The Cambridge edition of the Statutes at Large (1763) gave the date

as 1676, while the Statutes of the Realm (1819) dated it 1677.

The

apparent contradiction is explained by Lord Chesterfield's Act, (1751)

which effected the change from the old calendar to the Gregorian

Calendar.

A dual system of numbering years (old style and new style)

existed for a short time, but eventually uniformity returned.

These difficulties have given scholars much to debate with respect

to the enactment date. One writer has seemingly solved the problem by

extensive study of the journals of the House of C o m m o n s . I f the

entries therein are taken as correct, all evidence tends to show that

the Statute of Frauds was first read in the House on March 13, 1677.

It was read a second time on April 2, 1677.

On april 12, 1677, it was

reported from committee with arnenderaents which were also read twice.

And on April 16, 1677, the Statute of Frauds became law.

VI.

The lav: of real property conveyancing was possibly the hardest bit

by the Statute of Frauds.

In the first section thereof it is announced

that, beginning June 24, 1677, all "leases, estates, interests of

freehold, or term of years"

which were "created by livery of seisin

62

only, or by parol" ~

had to be written and signed by both grantor and

.grantee, or else they would be conclusively held to be estates at will

only.

At common law, an estate at will was created by implication, and

arose whenever one took possession of another's land.

103!

It was characteristic

page 13

oi' this estate that it could be terminated by either party vdthout

notice.

And it would end automatically if either party died or if

one attempted to convey his interest.^

The effect of this penalty provision was the loss of all the

advantages presumed to accompany the freehold and non-freehold estates.

Instead of enjoying the potentially infinite terra of a fee simple

estate, one who failed to comply with the Statute of Frauds would have

a fragile estate at will which could end at any moment.

And instead

of the security and predictability of duration afforded by a term of

years, one would face the prospect of having his estate vanish because

of the unforeseen early death of his landlord.

It should be noted,

therefore, that the changes wrought by this first section were more

than mere verbal alterations:

they were changes with a substantial

practical impact.

By the third section, a written deed or note, signed by the

concerned parties, was required for a valid assignment, grant, or

surrend of an estate listed in Section One.

and customary interest are exempted.

Only copyhold tenure

The reason for this exemption

was the fact that, unlike the other mentioned estates, copyhold and

customary interest were not created by feoffment and grant, but by

surrender and admittance.

The surrender and admittance were recorded

on the manorial court rolls and a copy thereof delivered to the new

tenant.

From this procedure came the name "copyhold".

In order to declare or create a trust in land, the seventh section

of the Statute of Frauds requires the same to be "manifested and proved"'

by a written, signed instrument," or else [it] shall be utterly void and

page

105

of none effect."^

It is the use of language such as this that

seduces scholars into agrument whether the Statute is evidentiary

or substantive.

The first quoted expression appears to be concerned

with proof; the second quotation seems to establish a substantive

sine qua non for the creation of an enforceable trust.

This is

further evidence, if any is needed, that the Statute of Frauds

suffered from the effects of too many authors.

Section Eight

exempted trusts which arose by implication, construction, or operation

65

of law.

Section Nine applied therequirement of a signed writing to

66

grants and assignments of trusts.

The effect of these sections of the Statute of Frauds was to

require better substantiation of interests in land than that afforded

by the memory of man.

Nothing is said about the content of the required

writing, or recording it, once it was vrritten. Nonetheless, something

should be written down describing the transaction and identifying

the parties thereto.

VII.

It is in the field of commercial lav;, especially the law of sales,

modern lawyers have dealings with what they know to be the "statute

of frauds".

These are laws that require particular sales agreements

to be in writing if they are to be enforceable.

The first of such

provision appeared in the fourth section of the original Statute

of Frauds.

That section declares

. . . [No] action shall be brought. . . (4) upon any

contract or sale of lands, tenements, or hereditaments,

or any interest in or concerning them . . . (5) or upon

any agreement that is not to be performed within the

105!

page 17

to the general requirement of a writing:

(l) partial delivery and

acceptance of the gcods sold, and (2) earnest money paid to bind the

bargain.

These items were held over from early common law, and were

by themselves thought to bind a sale. 75

One author states that th;^ seventeenth section was not viewed

by the business community as an aid to commerce, but rather as an

7 f>

impediment.

He found from his experience that many merchants

were reluctant to ask for either partial delivery or partial payment

out of fear of insulting the other party, who might regard such a

request as an intimation that he could not be trusted to keep

his word.

Nonetheless, Section Seventeen was generally seen as an inept

attempt by non-businessmen to regulate the subleties of every-day

commerce and viewed as successful only in creating more work for

attorneys.

VII.

The law of testamentary disposition of property is the final

major subject affected by the Statute of Frauds.

The fifth section

requires all wills involving interests in land to be in writing,

77

signed by the testator, and attested by three or four witnesses.

Section Seven extends these provisions to testamentary trusts of

78

interests in land.

Section Six states that any will made valid by Sections Five and

Seven shall continue to be valid until revoked either by physical act

79

or a later valid wall.

17!

page 18

Separate from the provisions on Written wills are Sections Nineteen through Twenty-one, which pertain to nuncupative wills.

A nun-

cupative will is sjmply a will made by the oral declaration of the

testator.

One can easily see the opportunity for fraud and perjury

present in trying to establish a dying man1s words as his will.

Thus,

nuncupative wills are a proper subject for regulation by the Statute

of Frauds.

By the second paragraph of Section Nineteen one learns that only

those nuncupative wills that bequeath an estate in excess of thirty

pounds are touched by this provision.

This seems to by an arbitrary

figure, as are most of the amounts cited by this statute.

Commen-

tators fail to discuss why a man might lie on a contract dealing with

more thsn ten pounds, but might not with regard to an estate under

thirty pounds. Perhaps the force of superstition would tend to make

men more honest when dealing with the property of the dead.

It is

more likely, however, that the choice of different amounts for contracts

and wills resulted from diverse authorship and not deliberate choice.

At least three witnesses who were present at the making of the

asserted nuncupative will must swear on oath as to the truth of the

matter.

Moreoverf they must prove that the decedent specially asked

some of his audience to bear witness that the words he spoke were

his last will.

This is included in the Statute of Frauds probably

as some objective evidence of the state of mind of the decedent

during the making of the supposed will, for a testamentary intent

80

was required at common law for the making of any vail.

As an added measure of fraud prevention, the fourth paragraph

18!

page 19

of Section Nineteen required that the alleged will be made during

the time of last illness of the decedent and in his or her own home,

or in another's home where the deceased had resided for at least ten

days.

The only exception to these rules was in the case of sudden

illness, when the decedent died before he could return home.

As with other provisions of this Act, doubt arose concerning the

requirements for witnesses.

It was finally announced by 4 Ann. c. 16,

6 14, that anyone who could be a witness at a trial could also be a

witness to prove a nuncupative will.

The effective limit of a nuncupative \-dll was set at six months

81

by Section Twenty.

If more than that time had elapsed since the

testator spoke his will, it could not stand as a valid will unless

it had been set down In writing within six days of its making.

Section Twenty-one makes rules for probate procedure with respect

82

to a nuncupative will.

It and Section Twenty vere probably intended

as safeguards and as direct evidence that the nuncupative will was

clearly an exception to the general rule requiring a writing for any

testamentary disposition.

As mentioned above, scholars are not in agreement about the

split of probate jurisdiction between ecclesiastical and secular

courts.

Section Twenty-four does nothing to settle the dispute,

but it does say that whatever jurisdiction the ecclesiastical courts

r>Q

have, they shall nonetheless be subject to the Statute of Frauds. ~

In the Nineteenth Century, probate jurisdiction was finally wrested

0h

from the church courts and bestowed upon a separate Probate Court,

which

was later

consolidated

with that of other special

courtsjurisdiction

by the Judicature

Act (1873).

Or

19!

page 20

VIII.

Although the original Statute of Frauds has been supplanted by

more modern legislation,^ its spirit lives on in American law by

its early adoption by the legislatures of the American colonies and

states. Either by specific reference or by general inclusion in the

entire body of common law, the Statute of Frauds found its way into

87

the laws of Virginia, Delaware, New York, and other colonies.

The American law of probate tended to follow English examples,

88

usually the Statute of Frauds or the Wills Act of 1837.

The

English law of contract was also closely copied, especially in

89

highly commereialized states such as New York.

And even in Texas the English Statute of Frauds had made its

presence felt.

In the field of contract lav?, Texas adopted Section

90

Four of the Act as its earliest form of commercial regulation.

The first Texas Statute of Frauds tracked the language of its ancestor

exactly, and even added a clause to bring the sale of slaves within

the Act.

The rules governing wills and probate were taken out of the

English Statute of Frauds by the first Texan legislators and placed

91

in a separate statute entitled "An Act Concerning Kills,"

This law

empowered everyone of sound mind and at least twenty-one years of age

to make a will.

It calls for a writing and the signature of the testator,

along with those of his witnesses.

law.

But then it departs from the common

Texas, of course, had been under the civil law influence of

Spain and France.

And from the civil law came the notion of the

holographic will.92

A holographic will is a testamentary writing

111

page 21

wholly in the testator's handwriting.

The Texas lav; declared that no

witnesses were needed for such a will.

Surprisingly enough, that is

93

still the law in Texas.

Thus, Texas requires attestation by two or more witnesses only

when the instrument is not written wholly in the testator's handwriting,

whereas the English law required three or four witnesses in every

instance. One might conclude that experience demonstrated to the

Texas lawmakers that there is little opportunity for fraud or perjury

where it is shown that the decedent personally wrote every word of

his will.

But it is also possible that the change in formalities

was due to feelings similar to those expressed by Lord Mansfield

when he said, "I am persuaded many more fair wills have been overturned

for want of the form, than fraudulent have been prevented by introducing

IX.

The success of the Statute of Frauds, or at least the concept

of a law to prevent fraud, can be measured not only by the comments

of judges and authors who, in their turn, applied and criticized the

Act, but also by the number of other jurisdictions which followed the

Statute as a model for their own laws.

Every jurisdiction which follows

the English tradition has its own statute of frauds, though not always

in the same form.

What was expressed in twenty-five sections of one

law is now, dur to the complexity of modern society, scattered throughout

the entire body of the laws of most states.

It was remarked by Stephen and Pollock that the Statute of Frauds

did nothing more than hinder the efforts and disappoint the expectations

21!

page 22

of honest men who failed to follow the law to the letter-

Though

this mighl have been true in some cases, the Act was generally successful

despite its weaknesses.

It was in many respects a stark and sudden

change from the common law.

As such it was bound to meet with oppo-

sition, for as Justice Story said, "Changes in the law, to be safe,

95

must be slowly and cautiously introduced, and thoroughly examined."

As mentioned above, many of the provisions of the Statute of

Frauds now endure in modern codes — Probate Codes,

Uniform Trust

96

Acts, Business and Commerce Codes, and others.

They have been

revised to fit modern society, but yet bear an undeniable resemblance

to their ancestor.

Time has shown the reforms brought about by the

Statute of Frauds were beneficial and much needed.

Perhaps those

who once criticized it would now agree that the Statute of Frauds

is one of the greatest legal innovations in history.

113

page 23

NOTES

1.

William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Vol. IV

(London: Dawson's oT'Pall Mall, I966)", "pp. 06-13"f." '

2.

]The_ Laws of the Kings of England from Edmund to Henry I,

A. J. Robertson, trans. (Cambridge: University Press, 1925).

See especially, II Canute cap, o; II Canute cap. 36; The

(So-Called) Laws of William I, cap. 23; VI Aethelred, cap. 7.

3.

William Holdsworth, A History_of English Law. Vol. IX (London:

Macmillan & Co,, 1935), p. 126. [Hereinafter cited as Holdsworth]

A.

Ibid.

5.

James Bradley Thayer, A J? reliminaryJTre at i se on Evidence, at the

Comrnon Law (Boston: Little,"Brownand Co". 7 "lS9S)"7"p."" 133. " *

[Hereinafter cited as Thayer, Treatise]

6.

Theodore F, T. Plucknett, AjConcise History of the_Common Law, 3d ed.

(London: Butterworth & Co., 1940)» p. 160. [Hereinafter cited as

Pluxknett]

7 • Ibid.

8.

James Bradley Thayer, "The Jury and its Development,"

Law Review, V (1891-92), 302.

9.

Ibid.

10.

Ibid.

11.

Plucknett, supra, at 160.

12.

Holdsworth, supra, at 131.

13.

Harvard

Plucknett, supra, at 611. See also Colin Rhys Lovell, English

Constitutional^ and Legal History (New York: Oxford University

P r T s V ^ T . P. 102."

14.

Simon Greenleaf, A Treatise on _the _Law_of Evidence (reprint) (New

York: Arno Press, 1972)) p. 358. [Hereinafter cited as Greenleaf]

15.

Greenleaf, supra, at 358.

16.

Holdsworth, supra, at 132.

17.

Ibid.

18.

Francis Bacon, "Of Judicature," collected in Essays and Hew /,tlantis

(New York: Walter J. Black, 1942), p. 22?.

23!

page

13

19.

Plncknett, supra, at 160.

20. Greenleaf, supra, at 229.

21.

Sources of English Constitutional History;, Carl Stephenson and

Frederick George Marcblm'v""eds, C Mew Yorkf Harper &*Row, 1937)

p. 5-

22. Op. cit., at 12.

23.

Sir Frederick Pollock and Frederic William Maitland, The History

of English Law, Vol. I (Cambridge: University Press, 196s),

pp. 57-58. [Hereinafter cited as P & M]

2A. James Barr Ames, Lectures on Legal History (Cambridge:

University Press," T9T3") , p. 122.

Harvard

25. P & M, Vol. II, p. 207.

26.

Ibid.

27«

P & H, Vol. II, p. 214.

28.

Henry Campbell Black, Law Pict.ionary,. 4th rev. ed. (St. Paul:

West Pub. Co., 1968), p.'537. [Hereinafter cited as Black's]

2

PlucJqiett, sunra.j_ at 326.

9*

30. Oliver Wendell Holmes, The_Comrn_onJ^aw (Boston:

1963), pp. 213 and 144-46".

31.

Plucknett, supra, at 326.

32.

Black's, supra, at 35.

33.

Ames, Lectures, supra, at 122.

Little, Brown, & Co.,

34. P_&.M» Vol. II, p. 222.

35.

Ames, Lectures, supra, at 122.

36.

P_jk.I1, Vol. II, p. 224.

37.

Ibid.

38.

Cornelious J. Moynihan, Introduction to the Law of Real Property

(St. Paul: West Publ. Co., 19S25", p."28.

~

"

39.

Kenelm Edward Bigby, An Introduction to jthe History of the Law of

Real Property (Oxford: Clarendon Press, T§75), pp.~104-105. ~

lis

page 25

40. Op. ext., at 168.

4-1. See generally Paul Vinogradoff, "Transfer of Land in Old English

Law," Harvard Lav? Review, XX (1906), 532-548.

42.

Thayer, The Jury, supra, at 307.

43.

Ibid.

44.

Ibid.

45. Moynihan, Introduction, suora, at 195) note 2.

46.

Ibid.

47. Plucknett, supra, at 666.

43. Jesse Dukeminier, Jr. and Stanley M. Johanson, Family Wealth

Transactions (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1972)", p. 11.

49.

Cassell' s New Latin Dictionary, D. P. Simpson ed. (New Yorir:

Funk & Wagnalis, 1959), p7 601.

50. D. Mellinkoff, The Language of the Law ( "Sost^

> Bw""1!

/kWti Co

51.

0£.

Cit., at

331.

52. Lovell, History, supra, at 69.

53.

Harcham, supra, at 49•

54. Stuart E. Prall, The Agitation for Law Reform during_the JPuritan

Revolution I64O-l^TTThe Hague: MartinuT'Nijhoff, "1966) ,"p"~51.

[Hereinafter cited as Prall]

55. Prall, supra, at 52.

56. IbicL

57-

P.rallt supr_a, at 121.

58. Ibid.

59. George P. Costigan, "The Date and Authorship of the Statute of

Frauds," Harvard Law Review, XXVI (1913), 329-346; James Schouler,

"The Authorship of the Statute of Frauds," American Law Review,

XVIII (1884), 442; Joseph Brightman, "The Statute "of Frauds'","

Ohio J,aw Bulletin, LVIII (1946), 331.

60.

Costigan, sugra, at note 59'

25!

page 26

61. Ihicl.

62. See copy attached as Appendix.

63.

John E. Cribbet, Principles of the Lav/ of Property (Brooklyn:

Foundation Press, I962), p. 56.

64.

See appendix.

65.

See appendix.

66. See appendix.

67.

See appendix.

68. Martin W. Cook, "The Seventeenth Section of the Statute of Frauds

and Perjuries," Albany Law Journal, XXXVII (1888), p. 494.

69.

See appendix.

70. James F. Stephen and Frederick Pollock, "Section Seventeen of the

Statute of Frauds," Law Quarterly Review, I (1885), pp. 1-24,

For sinilar articles see George P. Costigan, "Judicial Legislation and the Statute of Frauds," Illinois Law Review, XIV

( 1 9 1 4 ) , p. 1; Hiram Lilienthal, ".Judicial'Repeal of the Statute

of Frauds," Harvard Law Review, IX (1899), p. 455.

71.

Stephen, supra, at 2.

72. Op. cit., at 4.

73-

Ibid.

74. Ibid.

75>

See note 26, supra, and accompanying text.

76.

Martin VJ. Cooke, "The Seventeenth Section of the Statute of Frauds

and Perjuries." Albany Law Journal, XXXVII (1888), p. 494.

77.

See appendix.

78.

See appendix.

79.

See appendix.

80.

v

81.

See appendix.

82.

See appendix.

ol. II, pp. 314-56.

26!

page 27

83.

See appendix.

84.

20 & 21 Vict., c. 77.

85.

Stephenson and 14archain, _supra,_ at 750.

86.

Sections Seven, Eight, and Wine of the Statute of Frauds were

repealed by the Lav; of Property Act of 1925, and were

re-enacted by Section 53 of that Act.

87.

Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (Hew York:

Simon and Schuster, 1973)*; pT 96.

88.

Friedman, supra, at 219.

89.

Op. cit., at 246.

90.

The Laws of Texas, compiled and arranged by H. P. N. Gammel,

Vol. if "(Austin: Gammel Eook Co., 1893), p. 28.

91.

Op. cit., at I67.

92.

Friedman, sup£a, at 219, note 36.

53.

Texas Probate Code, 1973 ed. (St. Paul:

Section 6b, p. 39*

West Pub. Co., 1973),

91. Windham V. Chetwynd, 1 Burr. 420 (1757).

95.

Joseph Story, Equity Jurisprudence, Vol. I (Boston:

Brown, & Co., 1834), p. 61.

96.

The early statute of frauds provisions referred to at note 90

have under gone many revisions, but are now contained much as

they began in the Texas Business and Commerce Code, Article 26.

113

Little,

page 28

BIBLIOGRAPHY"

Agnew, William Fisher. A Treatise, on the Statute of Frauds.

London: Wildy and Sons, I876.

Ames, James Barr. Lectures_on Legal History.

University Press, 1913-

Cambridge:

Harvard

Bacon, Francis. "Of Judicature." Es_s_ays and New Atlantis.

New York: Walter J. Black, 1942.

Black, Henry Campbell. Law Dictionary.

West Pub. Co., 1968.""

4th rev. ed.

St. Paul:

Blackstone, Sir William. Commentaries, on the Laws of England.

Oxford: Clarendon Pr'ess'7 17*69.

Bogert, George Gleason. Handbook of the Jlav.' of Trusts.

West Pub. Co., 1921/"" ~~

Brightman, Joseph. "The Statute of Frauds."

58 (1946), 331.

4 vols.

St. Paul:

Ohio Law Bulletin,

Browne, Causten. A Treatise on the Statute of Frauds.

Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1880.

Conard, A. F. "Easements and the Statute of Frauds"

Law Quarterly, 15 (1941), 222-240.

4th ed.

Temp],e University

Costigan, George P. "The Date and Authorship of the Statute of Frauds."

Harvard Law Review, 26 (1913), 329-346.

"Judicial Legislation and the Statute of Frauds"

Illinois Law Review, 14 (1914), 1.

Cribbet, John E. Principles of the Law of Property.

Foundation Press,"1962.

Brooklyn:

Cook, Martin W. "The Seventeenth Section of the Statute of Frauds

and Perjuries" Albany_^WjJonrnalT 37 (1888), 494.

Digby, Kenelm Edward. An Introduction to the History of the Law of

Real Property. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1875.

Dukeminier, Jesse and Stanley M. Johanson. Family Wealth Transactions.

Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1972.

Finch, Sir Henry.

1759.

Law, __or a_ Discoursehereof.

28!

London:

Henry Lintot,

Friedman, Lawrence M. A History of American_Law.

and Schuster, 1973-

New York:

Greenleaf, Simon. A^Treatise on the Law of Evidence.

Arno Press (reprint), 1972.

Simon

New York:

Hawkins, William. An Abridgment of the First J5art of Lord Cokejs

Institutes. Sth~ed7 ~ Dublin:TT'Watts," 1132.

Holdsworth, William; A Historyof English^Law. 15 vols,

Methuen & Co., 1937

Holmes, Oliver Wendell.

and Co., 19&3-

The Common Law.

Boston:

London:

Little, Brown,

Ireton, R. E. "Should We Abolish the Statute of Frauds?"

States Law Review 12 (1938) , 195-20/+.

The Laws of the Kings _of_ England_From Edmund to Henry_I.

ed. Cambridge: University Press, 1925.

United

A. J. Robert

Laws; of_TexaSj__ 1822-1897. Compiled and arranged by H. P. N, Gammel.

Austin; Gammel Book Co., I898.

Lilienthal, Hiram W. "Judicial Repeal of the Statute of Frauds"

HarvardJLaw Review, 9 (1896), 455-463.

Littleton, Sir Thomas. Treatise^of Tenures,

T. E. Tomlins ed.

New York: Russell FSussell" (reprintj, 1970.

Lovell, Colin Rhys. English Constitutional and Legal History.

New York: Oxford University Press," 1962,"

McKeehan, Joseph P. "The Statute of Frauds"

25 (I92.O), 63-71.

Haiti and, F. W.

Cambridge:

DickinsonJLaw Review,

Equity..

A. H. Chayton and J. Whittaker eds.

University Press, 1936.

Hellinkoff; David. TheLanguage^of_the_Law.

Brown, and Co., I963.

Boston:

Little,

Moynihan, Cornelious J. Introduction to the Law of Real Property.

St. Paul: West Publ, Co.~1962."

Plucknett, T. F. T. A Concise History of the Common Law. 4th ed.

London: Butter-.-orth & Co. , 1948.

Pollock, Sir Frederick and Frederic William Maitland. The_ History of

English Lsw. 2 vols. Cambridge: University Press, 1968.

31

page 30

Prall, Stuart E. The Agitation for Lav? Reform During theJPuritan

Revolution I6l0-'l6~60. "The Hague": Martinus Nijhoff, "19557'

Reeves, John. History of the English Law,

E. Brooke,"1787»

4 vols.

2d ed.

Roberts, William. A Treatise on the Statute of Frauds.

I. Riley & Co.", 1807

London:

London:

Schouler, James. "The Authorship of the Statute of Frauds"

American Law Review, 18 (1884), 442.

Sources of English Constitutional History. Carl Stephenson and

Frederick George Marcham eds. New York: Harper and Row,

1937.

Stephen, James F. and Frederick Pollock. "Section Seventeen of the

Statute of Frauds" Law Quarterly Review, 1 (1885), 1-24.

Storke, F. P. "Collateral Effects of the Statute of Frauds."

Rocky Mountain Law Review, 13 (1941), 233-241.

Story, Joseph. Commentaries on Equity Jurisprudence.

Boston: Milliard, Gray, & Co., I836.

2 vols.

Sugden, Sir Edward Burtenshaw.

London: S. Sweet, 1849.

A_Treatis_e _of the Lav? of Property.

Texas Probate. Code.

West Pub. Co., 1973.

St. Paul:

Thayer, James Bradley. "The Jury and its Development"

Law Review, 5 (1891-92), 302.

Law.

Boston:

Harvard

. A .Preliminary. Treatise on Evidence at _Common

Little, Brown, and Co., 1898.

Vinogradoff, Paul. "Transfer of Land in Old English Law."

Lav; Review, 20 (1906) , 532-548.

30!

Harvard

Anno Regni C a r o l i IT. Regis Anglia,

Scotia,

Francis?, & Hibernian, viccfinw fcptimo.

T the parliament begun at Weftminfter the eighth day

jTk of May, Anno Doir.. one thcufavd fix hundred fixlycnej in the thirteenth year cf the reign cf cir moji gracious

fever cign lord Charles, by the grace of Cod, of England,

Scotland, France and Ireland, King defender of the faith,

&c. and there continued by fever al'prorogations to the thirteenth day of October one thoufand fix hundred feventy-fve.

A n a f t f o r the better and m o r e enfy rebuilding the t o w n o f Northampton.

A court o f record CO!"ftituted. H o w to proceed, and what to determine

between landlord and tenant, 6:c. Defalcation or apportioning of resit.

B o d i e s politick. Definitive order to be fin:'.'!. P o w e r to make a decree

to charge, k c . an efiate, or to order a new or l o n g e r ellate to be made,

r.ouvithltanding i n f a n c y , coverture, $;c. I n f a n t s , Sec. Bifhops, &c. Corporations. T o m a k e rules and d i l u t i o n s in the f o r m s and orders cf

buildings. T o enlarge or alter ftrects, lanes, roads and palTages. T o

treat and compound for g r o u n d to be uf'cd f o r thole purpofes, In cu'.c

of refufal or diiability by i n f a n c y , & c . then to impanel a jury. T o make

alterations in the f o u n d a t i o n s , if they fee caui'e. S a t i s f a f t i o n to be

a w a r d e d . A jury to be impanelled in cafe of diiability. A provifo not

t o take away any g r o u n d , but only f o r enlargement ot the frreets. T h e

c o r n e r houfe taken a w a y . Several other houlcs to be taken away. It'

a n y perfon (hall not build within three years, then the court to clilpol'e

of the g r o u n d to liich perfon as will build. Satisfaction to be made so

t h e proprietor of the foil. I n cal'c of r e f u f a l a j u r y to be impanelled. All

houies to be covered with lead, llate or tile. Perilous trades prohibited.

P e n a l t y . T o appeal f r o m an order made by lefs than feven of liic

j u d g e s . A review of the decree. C o d s . A l l j u d g m e n t s and dee'rers

ilia]t be good both in law and equity. 'There lhall iie no writ of error

o r certiorari.

A regiiter-book for the orders to be kept by the mayor.

A l ! juliices of the county that inhabit in the town, (liall be jultices in

the town. A n y perfon that (hall build a houfe worth 300I. to luive

thereby his f r e e d o m . A l t perfons that e x e c u t e any power by this a f t to

t a k e an oath. T o plead the general ifl'ue.

Anno

Regni

C a r o l i I I . Regis

o

o Aiwlia,

o ' Scot he,

Francicc,

& Hibernicv,

viccfnno nono,

f\ T the parliament begun at Weftminfter the eighth dcy

i~.%. of May Anno Dom. one thoufand fix hundred finiyone. in the thirteenth year of the reign of our moji gracious

fovereign lord. Charles, by the grace of God, of England,

Scotland, France and Ireland, King, defender of the faith,

ccc, and from thence con tinned by fever al prorogations re

the fifteenth cf February one thoufand fix hundred fevcutv-/?x,

CM'.

C A ]'. 1.

An "ft for railing the I"11'!1 cl~ live hnmlrcd eifdiiv-fytr thoufaiid nine

liM:n!r'.-.l (evrmy ci";'nt jk>«.v5; two ;1>ii!in£S and n>o-):vu<c !..;'• I-pvi.y,

{;:: v!is Jpeccly bui! •'•'"j thi.-ty fta>-; of war. K X I ' .

C A P . II.

An aft for an additional excite upon beer, ale and otlicr bipicrs, for three

years. HX1'.

C A P . III.

An c.of for prevention cffrauds av.d

-perjuries.

7 7 0 1 1 prevention of nuv:y fraudulent profilces^ ',dub ere csmmsr- iRo!!.Abr.i.>.

J.' ly endeavoured to he upheld by perjury and ji' .-.-nation of perjury ; ( 2 ) be it c n a & c d by the K i n g ' s m o d excellent M a j e f t y ,

'by and with the advice unci content of the l o r d ; fpiritual and

temporal, and the c o m m o n s , in this prefonr parliament a f fembled, and by the authority of the f a m e , T i i u t iron) and 'after the f o u r and twentieth day of June, which shall be in the

year of our L o r d one ihoufand fix hundred feventy and fever),

all leafes, eftatcs, interefts of freehold, or terms of years, or Parol leafes

any uncertain intercft o f , in, to or our of any ineffuagcs, m a - and imertil

norSj lands, tenements or hereditaments, made or created by

'jJpJ1^, e

livery and feiftn only, or by parol, and not put in writing, and forcc oftfiatcs

ligr.cd by the parties fo making or creating tire fame, or their a t will only,

agents thereunto lawfully authorized by writing, lhali have the

forcc and effect of leafes or eftatcs at will o n l y , and (hail not

either in law or equity be deemed or taken to have any other

or greater forcc or e f f e c t ; any coniideration for making any

fuch parol leafes or eftatcs, or any former law or ufage, to the

contrary notwithftanding.

I I . E x c e p t nevertheiefs all leafes not exceeding the term of Except leafes

three years f r o m the making thereof, whereupon the rent re- potexecedferved to the landlord, during fuch term, fhall amount unto two

third parts at the lead of the full improved value of the thing ' ' '

demited.

I I I . A n d moreover, T h a t no leafes, eftates or interefts, cither No leafes or

of freehold, or terms of years, or any uncertain intercft, not states ot treebeing copyhold or cuftomary intercft, o f , in, to or out of any

m e f f u a g e s , manors, lands, tenements or hereditaments, (hall l u r V i - i u h b y

at any time after the (aid four and twentieth day of June be word,

afligncd, granted or furreudrcd, unlefs it be by deed or note in

writing, figncd by the party fo affigning, granting or furrendring

the f a m e , or their agents thereunto lawfully authorized by

writing, or by adt and operation of law.

I V . A n d be it further enafted by the authority aforefaid, Promifcs and

T h a t from and after the faid four and twentieth day of June no

?d':on fly!! be brought whereby to charge any executor or ad- " J 1 '

miniftrutor upon any fpccial prornife, to anfwer damages out

of his own eftate ; (?.) or whereby to charge the defendant

upon any fpccial prornife to anfwer for the debt, o 'fault or ruifcarriages f-t another penon ; ( 7 ) or to charge any parfon upon any . g !

(

sgrcetncnt made upon confidei ation of m a r r i a g e ; (,j.) or upon si-';,,,,

Pel 3

"

'

;uiyH3,

.|0()

/uino vlerfimo ucno C / R O M II. en;.

f iG-f,.

a

i

•

>!•••!. sic. any contrail or fa!c of hnc's, tenements or hereditaments, or

\ .-.ut.

iijiercO; in or concerning t h e m ; ( 5 ) 0 1 - upon any :»»»rccany

i'r- c- Ci J ' n, -' lU 1 hat

not to be performed within the fpace of one yc .r

v^tk. sGj. f r o m the making t h e r e o f ; ( 6 ) unlcfs the agreement upon which

f « c h action (hall be brought, or fome tnernnvuhm or note

thereof, (hall be in writing, and figned by the party to l.»

charged therewith, or fome other perfon thereunto by hi:n

lawfully authorized.

j\.vifcs of

V . A n d be it further cna&cd by the authority aforefaid, T h a t

lands 1 liall be from and, after the laid four and twentieth day of "June all doi:i '.Mating and v j f c s n i i c j bequeds of any lands or tenements, devifable either

t!u''U'o-''o'il- '°y f ° r c e ° f the Aate.te of wilis, or by this Aatute, or by force

\vitneif'.''

of the cuftom of Kent, or the cuftom of any borough, or any

31.ev. sfi.

other particular cuftorn, (hall be in writing, and figned by thlCarthc.Y 35. party fo devifing the fame, or by fome other perfon in his prei'di- v Smith tbnee and by his exnrefs directions, and fiiall be attelled and

in chan. iiiijV* fubferibed in the prefenee of the laid devifor by three or four

j ^54..

credible witncfTes, or elfe they (hall be utterly void and of none

en eel.

How the fame

V I . A n d moreover, no devife in writing of lands, tenements

liiail be revo- or hereditaments, nor any elaufe thereof, (hall at any time

after the faid four and twentieth day of June be revocable, othcrt - r i '-Jco.'^' v , ' ' l c than by fome other will or codicil in writing, or other

writing declaring the fame, cr by burning, canccIling, tearing

or obliterating the fame by the tefhtor himlelf, or in his prefenee and by his directions and confent ; ( 2 ) but all devifes

and bcqucfts of lands and tenements (hall remain and continue

in force, until the fame be burnt, cancelled, torn or obliterated

by the teftator, or his directions, in manner aforefaid, or unlcfs the fame be altered by fome other will or codicil in writing,

or other writing of the devifor, figned in the prefenee of three

or four vwtnefies, declaring the f a m e ; any former Jaw or ufage

to the contrary notwithstanding.

A!! declaraV I I . A n d be it further enabled by the authority aforefaid,

tiuin: or o ca- T h a t from and after the faid four and twentieth day of June all

i'nlVb" i n " ' ' declarations or creations of tsv.fts or confidences of any lands,

wririug.'

tenements or hereditaments, (hall be manifefted and proved by

j:\ftuiKtJh

feme writing finned by the party w h o is by law enabled to deAnn. c. 16. c j s r c f u c h truff, or by his laft will in writing, or elfe they lliall

'' 1 5 '

be utterly void and of none eftech

Trot*:? arifing,

V I I I . Provided always, T h a t where any conveyance lhall he

rram-serrctl or n -, ac ] e of any lands or tenements by which a truft or confidence

or ma

or re u t

bV'i'no'• c-r'ion

y

f ' by the implication or conftru&ion. of

r.f h'.v, are

l a w , or be transferred or extinguished by an adl or operation

excepted.

of l a w , then and in every fuch cafe fueli truft or confidence

Ih-;/:! V. Spillit |1 1S ]1 be of the like force and cfFeft as the fame would have been

j!.™^'

' if this Aatute had not been m a d e ; any thing, herein before

contained to the contrary notwithstanding. "

Aifi^nments

I X . A n d be it further enactrd T h a t all grants and afFgnott-uito'h.;;!b° rr.ents of any trufc orconiidcp.ce .hall likewife be in writing,

;•) ',v.-i'.::i;;.

figned by the party granting or afiigning the f.im?, or by fuch I a It

v/illordevifcj or elfe (hall likewife be utterly void and of none effect.

.X. And

:6'/(>.]

Anno vkcl'vr.o nor.o C a k o m jl. c.j.

X . A n d be it f u r t h e r enabled bvJ the authority

r ,

r

f

•

407

aforefaid, T.am-', .v.-.

1 1 ' ' ' '

T h a t f r o m a n d aft'.'.- d i e (aid f o u r n . i J twentieth day of 'J.//:c it

J.^/'f;'^'

.".tall and m a y be lawful f o r every iherifF or ether cli.eer to ^ . - • V ' k - c V

w h o m any writ or precept is or fhall be dire.-Vd, at the f.r.r

.«,....;.

of any perfon or perfon::, o f , for and upon any jut1.;-.menu

:lute or r e c o g n i s a n c e hereafter to be made or h a d , to d o , m a k e

and deliver execution unto the party in that behalf filing, of all

f u c h l a n d s , tenements, rectories, tithes, r e n t , and hereditam e n t s , as any other perfon or pcrfons be in any m a n n e r oi wife

feifed or pofielTed, or hereafter fhall he feifed or poffefied, in

trufl for h i m againfl: w h o m e x e c u t i o n is f o f n e d , like as the flu >'iff

or other oiliccr m i g h t or o u g h t to have done, it the raid party

a g a i n f l w h o m execution hereafter fhall be fo fried, had been

feifed of fuch l a n d s , tenements, rec'lories, tithe-;, rents o r

other hereditaments of f u c h eftate as they be feifed of in truft

for h i m at^thc t i m e of the laid execution fued ; ( a ) wliich lands, A-.u'. held free

llv in

t e n e m e n t s , rectories, tithes, rents and other hereditaments,

- ; .

by forcc and virtue of fuch execution, lliall accordingly be held X ' P - ' i I m w ° f

and enjoyed freed a n d difcharged f r o m all i n c u m b r a n c e s of f u c h iciiw: in truft.

perfon or perfons as fhall be fo feifed or poffeffed in trufl f o r t!;e

p e r f o n a g a i n f t w h o m f u c h execution fhall be fued ; ( 7 ) and if T n r t

be

a n y ctfiuy que trufl hereafter fhall die, leaving a t i n ft in fee- h-usds oVlll^rs

fimple to defccnd to his heir, there and in every fuch. cafe f u c h l Veni. •..a.

truft fhall be deemed and t a k e n , and is hereby declared to h e ,

a Acts by defcent, and the heir fliall be liable to and chargeable

w i t h the obligation of his a n c c f l o r s f o r and by reafon of f u c h

affets, as f u l l y and a m p l y as he m i g h t or ought to have b e e n ,

if the eftate in law had dcfcendcd to h i m in poflefiion in like

m a n n e r as the t r u l l ciel'ccnded ; any l a w , c u f t o m or ufage to

t h e contrary in any w i f e n o t w i t h f t a n d i n g .

X I . P r o v i d e d a l w a y s , T h a t no heir that fliall b e c o m e charge- N'o heir fliall

able by reafon of any cftatc or trufl: made affets in his hands by

tills l a w , fhall b y reafon of any kind of plea or confeftion of C 0 l j,„ c |, : „" rc _

the action, or fullering j u d g m e n t by wait dcdlre, or any other able of hi*°

m a t t e r , be chargeable to pay the c o n d e m n a t i o n out of his o w n o v v n ellate.

eflate \ (?.) but execution fhall be fued of the w h o l e eftate fo

m a d e aflets in his hands by defcent, in w h o f o hands foever it

fhall c o m e after the writ p u t c h a f c d , in the f a m e m a n n e r as it

is to be at and b y the c o m m o n l a w , w h e r e the heir at l a w

pleading a true plea, j u d g m e n t is prayed againft him thereupon ; any thing in this prcfent a i l contained to the contrary

notwithftanding.

X I I . A n d f o r the amendment: of the law in the particulars Eftatcs//.r

f o l l o w i n g ; (2) be it f u r t h e r enacted by the authority nforcfaid, {"'/'.''^'V.^i1'.1

T h a t f r o m henceforth

anyJ cftatc *fur nutcr Sic. fliall be .devifable 1 J.v.i , 1 . V •'?• O»

.

b y a will in w r i t i n g , figncd b y the party fo deviling the f a m e , or f.n.

by fome other perfon in his prcfcncc and by his exprefs directions, attcfted end ' " b f e r i b e d in the prelen.ee of the devifor b y

three or more wit:,cf.es ; ( 3 ) and if no fv.eh

'.• thereof be

^...n l v .

m a d e , the fame fliall be chargeable in the hand.: <;•! the heir, if : „ r , . ( s t ! . „ .

it. flv.dl come to h i m by reafon of a fpeciai occupancy as aulas by bcire ha:;.!.

D d 4.

def.-enr,

.•OB

Anno

VI^CFT'TIO

nrno C A R O L I

! I . C-%,

YTC.-'

A r! v.vc-.-e

'•:• " 1 1 0

'•'"> in cafe of bm'.s in fec-fimple ; (4) and in cafe there he r,>

fpecia! occupant thereoi, ii Avail go to the executors or ndminiftrators of the pat tv that hau the eftate thereof by virtue of the

lo'thVcxecu- S r n n r > ; 1 I K - fhall he'adi.'ts in their hands,

vers. Car'Jr.av 376. » Saik. 464.. 5 Vera. 719.

The day or

X [II. And whereas it hath bent found vrfchievous, that judrnunu

in the King's courts at Wcilniinfter do many times re/ate to the f:r:>

diy efthe term ivhereoj they are erJred, or to (he day cf the return

the eric inn!, or fling the hi/, and bind the defendants landsfrom thai

time, although in truth they were acknowledged or ftffererl and f.g'i; I

in the vaection-tini; after the Jaid term, zvbtrcby many times purdxfcrs find! hemfelves agrievrd:

iisninr; any

X I V . JJc it enabled by the authority aforefaid, T h a t from

arK 1

111 dTbe'^en

' after the faiu four and twentieth day of June any judge or

tred on the

officer of any of his M a j e A y ' s courts (1 JVejlmiuj/cr, that lhall

mar^eiH of fign any judgments, fhall at the figning of the fame, without fee

the roll. ^

for dcing the fame, fet down the day of the month and year of

doing, upon the paper book, docket or record which he

puforiii- fy-Y fhall fign ; which day of the. month and year (hall be alfo cn0'.;o 1. c".

tred upon the margent of the roll of the record where the laid

*'•

judgment fliall beentredA 1 ' - <bch

XV. A n d be it cnacled, T h a t fuch judgments as againft

P u r c l i a ' V r s bona fide f o r valuable com'idcration of lands, teneaiu r- iii dVre- ments or hereditaments to be charged thereby, fliall in conlilate to fuch

deration of law be judgments only from fuch time as they fliall

time only.

be fo figned, and (hall not relate to the firft day of the term'

whereof they areentrcd, or the day of the return of the original

or filing the bail ; any lass', ufage 01' courfe of any court to the

contrary notsvi th fla nd ing.

Writs of exX V I . A n d be it further enacfted by the authority aforefaid,

n ter

b=iid°H ' " ^o

'"rom

^

f ° u r ; i n c i twentieth day of June no

pray of roods v , r ' t

fac'wi o r other writ of execution fliall bind the probvi't Vront the' pcrty of the goods againfl: w h o m fuc.h writ of execution is fued

time P? their forth, but from the time that fuch writ fhall be delivered to the

lheriff, under-flieril'f or coroners, to be executed : and for the

j s-ip 1 A j

better manifeftation of the fain time, the lheriff, undcr-fherilT

Can!>tw"4.15. and coroners, their deputies and agents, fliall upon the receipt

i Mi;d. lis', of any fuch writ, (without fee for doing the fame) cndorle upon

i k - . b . i<7.

the back thereof the day of the month or year whereon he or

„ ( r

they received the fame.

X V I I . A n d be it further ena&etl by the authority aforefaid,

for tea pounds T h a t from and after the faid four and twentieth day of June

' r more.

110 contrael: for the falo of any goods, wares and merchandizes,

:il

'-an.Jiirt. f o r t | l e p r ; c e o f t e n pounds flerling or upwards, fliall be allowed

39' •• »S' to be good, except the buyer fhall accept part of the goods foible!, and actually receive the fame, or give iomething in earned

to hind the .bargain, or in parr of payment, or that fome note or

tmn'ir.'.ndnrr. in writing of the faid bargain be made and figned

by the parlies to be charged by feeh contrary or their agent?

thereunto lawfully authorized,

XVIII. And

Anno v k e f h i c nor;o CAROLI II. c . 3 .

400

X V I I I . And be it further ma-fhd by the authority aforesaid, The day of

That the dayJ of the month and year of the enrolment of tin.

«'»'olii»nir

,

' • ,

- ,

,, ol reei•.' !!recognizances than be let down in the margent ot Hie r o i l ; n , , l i j | s

where the faid recognizances are enrolled ; (?.} ;.:id th.\: from d-i down, and

and after the faid four and twentieth day of '/'</,•/:• no reeognihulic

•zance (hall bind any lands, tenements or hereditaments in the

}'"'':

hands of any purchafer bona fide and for valuable eontiderafion, )•'.';''

but from the time of fuch enrolment; -any law, ulagc or courie.

only,

of any court to the contrary in any wife notwithstanding.

X I X . s/nd fir prevention of fraudulent prettier; in jetting up Nuncupative

nuneupatine wii/s, which have been the oceafion e-J muthpenny

; (•?.)

be .it cnadled bv the authority aforefaid, T h a r Iror.i and alter

the aforefaid four and twentieth day of June no nuncupative

will (hall be good, where the eftate thereby bequeathed (hall e x ceed the value of thirty pounds, that is not proved by the oaths

of three witnefles (at the leaft) that were prefent at the making

thereof; ( ? ) nor unlcfs it he proved that the tedalor at the lime E.rpMneAly

of pronouncing the fame, did bid the perfons prefent, or feme + -Vnn. c. 16.

of them, bear witnefs, that fuch was his will, or to that eftcct ; '*

(4) nor tmlefs fuch nuncupative will were made in the time of

the lad iicknefs of the dcceafed, and in the houfe of his or her

habitation or dwelling, or where he or flic hath, been refident

for the fpace of ten days or more next before the making of

fuch will, exccpt where fuch perfon was furpriy.cd or taken lick.,

being from his own home, and died before he returned to the

place of his or her dwelling.

X X . And be it further enacted, T h a t after fix months paded

after the fpeaking of the pretended teftamcntary words, no

teftimony (hall be received to prove any will nuncupative, except the fuid teftimony, or the fubftance thereof, were committed to writing within iix days after the making of the faid will.

X X I . And be it further enacted, T h a t no letters teftamen- p,. 0 i, ;if£S OTtary or probate of any nuncupative will (hall pals the feal of any mmaipauvc

court, till fourteen days at the leaft after the deeeale of the lef- wills,

tutor be fully expired; ( 2 ) nor lhall any nuncupative will he at

any time received ro be proved, unlefs procefs have (irll il'fued

to call in the widow, or next of kindred to the deeeafed, to the

end they may conteft the fame, if they pleafe.

X X I I . And be it further enaelcd, T h a t no will in writing Raymond3;.y.

concerning any goods or chattels, or pcrfona.I etlale, lhall be repealed, nor (hall any claufe, devil'e or beij'ueft therein, be altered

or changed by any words, or will by word of mouth only, except the fame be in the life of the tenator committed to writing,

and after the writing thereof read unto the teflator, and allowed

by him, and proved to be fo done by three witnelles at the leaft.

' X X I I I . Provided always, T h a t notwithstanding this ae;. any soldier- and

foldicr being in aiftual miiitary fcrviee, or any mariner or fc.i- mariners-.viils

man being at fea, may difpoie of his move.-'Yi:.?, wages and per- excep'ed.

ion a' eftate, as lie or they might have done before the making

of this a(51.

X X I V . And it is hereby declared, T h a t nothing in this nT The juiKd'.

(ion i>;' court,

laved.

^

•>"°

Anno vlcclnr.o nono C A R O L I II. c.4,5.'

[10

fnall e x t e n d t o a l t e r o r c h a n g e t h e j u r i s d i & i o n o r r i g h t o f p r c l v

c f wills c o n c e r n i n g p c r f o n a ) c t b . r e s , b u t t h a t t h e p r c r ; . - ^ - . ,

c o u r t o f t h e a r e h b i f h o p o f Canterlary,

a n d o t h e r ecckf.V,'......

c o u r t s , a n d o t h e r c o u r t s h a v i n g r i g h t t o t h e p n . ' v.e

j'L,

w i l l s , fhall r e t a i n t h e f a m e r i g h t a n d p o w e r a s t h e y had before,

i n e v e r ) ' r e l p e c t ; fubjeel n e v e r r h c l c f s t o t h e r u l e s a n d ti.-ccil.,-;

o f this a c t .

si & s j Car.

X X V .

A n d f o r t h e e x p l a i n i n g o n e a f t o f t h i s prefent p:ir-

-• c. 10.

liamcnt, intituled, An act for the Latter fitting

make'diitri"- 10

'oution ct'the

pei fonal

thdr'vtfvcs

t Mod, 5 - 1 .

( a ) b e it d e c l a r e d b y t h e a u t h o r i t y a f o r e f a i d , T h a t neither the

!aid

a c t , n o r a n y t h i n g t h e r e i n c o n t a i n e d , lhall be confirmed to .

e x t e n d t o t h e e f t a t c s o f f e m e c o v e r t s t h a t fhall die inteltate, hut

t h a t t h e i r h u f b a n d s m a y d e m a n d a n d h a v e a d m i n i f t r a t i o n t1'

t ~ i e n " r i o ' l t s ' c r e d i t s , a n d o t h e r p e r f o n a l c f t a t e s , a n d r e c o v e r and

e n j o y t b e f a m e , a s t h e y m i g h t h i v e d o n e b e f o r e t h e m a k i n g of

t h e faid a c h

Made perpetually

1 Jac. 2. c. 1 7 . f i 5 .

cf inteflcus

tfla-::;

C A P." I V .

A n a f t f o r e r c f t i n g a judicature to determine differences touching houft;

,

burnt and deinoiifhed by tho late dreadful fire in South-,vark.

W h orti-.il1 be commiflioners. T h e i r power and m a n n e r of proceeding.

T h e i r decrees (hall be binding and conclufive, T h e i r fummons of p'u .

t i t s and witr.eil'es how to be g r a n t e d . A n d how to be ferved. b'-o 71

default tlicy may proceed to determine the controverfy. If the pericr.i

cannot be f o u n d to be f u m m o n c d , no proceedings (hall be tlureo.i ,.':!

after fix months. T o f t s of fuch as will not begin to build within r,u,

years, & c . may be difpofed of to fuch as will build. A n d iatisfactien

awarded to the proprietors. Or afTellcd by a jury where the parties v,i:l

r.ot or cannot accept the fame. Decrees made by fewer than (even, sr.-l

excepted to within thirty days, may be reverfed or altered by any (even

or m o r e ,

Such appeals r o b e fmiflicd within fix months. Such orders and decrees M l be effectual, and conclude all perfons. A n d not

reverfed by writ o f c r r o r or artiorari. Such judgments and decrees how

to be entred. T h e books to be kept by the town clerk of London.